When Life Hands Your Kid a Broken Toy: The Hidden Gift of Everyday Problems

My 10-year-old daughter stood in our kitchen last Tuesday, staring at her favorite water bottle like it had personally betrayed her.

The lid mechanism had jammed shut, trapping her after-school smoothie inside.

“Dad, it’s broken! Can you fix it?” she called out, already walking toward me with the bottle extended.

I almost took it. My hands were literally reaching out when something stopped me cold. Here was my daughter—a kid who could recite the water cycle, label all the parts of a plant cell, and score 100% on her spelling tests—completely stumped by a stuck lid. School had taught her that problems come with answer keys. Life was teaching her something different.

“What if we figured it out together?” I suggested instead.

The Problem-Solving Gap Nobody Talks About

Here’s what haunts me as a parent: Our kids are growing up in a world where problems arrive pre-solved. Homework has answer guides. Games have walkthroughs. YouTube has tutorials for everything. Schools teach kids to find THE right answer, not AN answer.

And we parents? We’re so busy protecting our kids from frustration that we accidentally rob them of their most powerful teacher: everyday challenges.

Think about your own childhood for a moment. Remember trying to fix that broken bike chain? Or figuring out how to retrieve a ball from the neighbor’s yard? Those weren’t just problems—they were problem-solving bootcamp. Today’s kids rarely get that training.

The terrifying part? By age 12, our children will face problems we can’t even imagine yet. Jobs that don’t exist. Technologies we haven’t invented. Challenges we can’t predict. And we’re preparing them with… multiplication tables?

Why Tuesday’s Stuck Lid Matters More Than Thursday’s Math Test

When my daughter and I sat down with that jammed water bottle, something magical happened. First, she wanted to throw it away. “It’s broken, Dad. We need a new one.”

But broken things are goldmines for developing minds. “Okay, but what if we couldn’t buy a new one?” I asked. “What if we were camping and this was our only water bottle?”

Her entire posture changed. Suddenly, this wasn’t about a broken bottle—it was about survival, adventure, possibility. She examined the lid like a detective, tried twisting it different ways, even grabbed a rubber glove for better grip. When that didn’t work, she wondered aloud if hot water might expand the plastic.

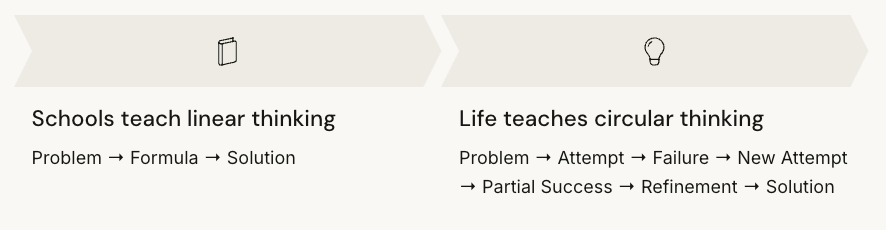

Schools teach linear thinking: Problem → Formula → Solution. But life teaches circular thinking: Problem → Attempt → Failure → New Attempt → Partial Success → Refinement → Solution. That stuck lid taught my daughter more about real problem-solving than a dozen worksheets ever could.

The Three-Part Framework I’ve Discovered

After the water bottle incident (yes, we got it open—dish soap around the rim was her winning idea), I started seeing opportunities everywhere. Here’s the framework I now use to transform everyday annoyances into problem-solving practice:

When your child encounters a problem, resist the urge to solve it immediately. Instead, ask: “Want to figure this out together?” This reframes frustration as curiosity.

The Permission Principle

When your child encounters a problem, resist the urge to solve it immediately. Instead, ask: “Want to figure this out together?”

This reframes frustration as curiosity. Last week, my 15-year-old son couldn’t get his backpack zipper unstuck. Instead of fixing it, I said, “Hmm, that’s interesting. Wonder why zippers get stuck?” Twenty minutes later, he’d not only fixed it but taught his sister about graphite lubricant.

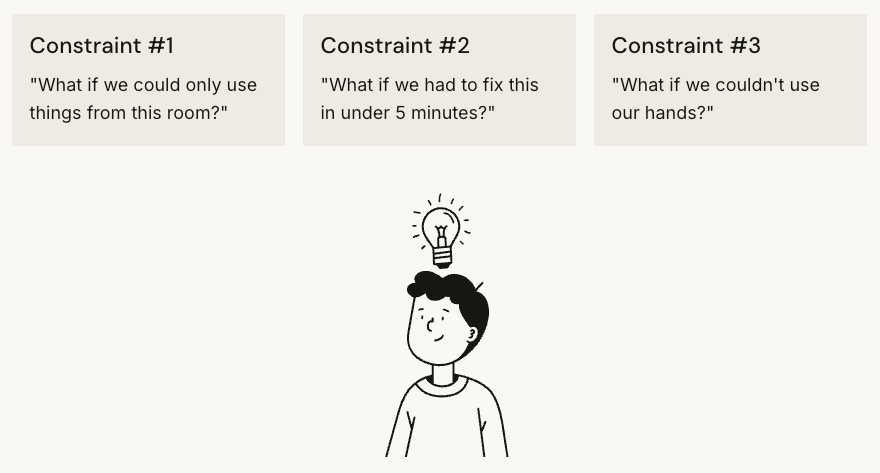

The “What If” Game

Add constraints to make simple problems more interesting. “What if we could only use things from this room?” or “What if we had to fix this in under 5 minutes?” My kids now beg to play this game. Yesterday’s challenge: How many ways can you pick up a pencil without using your hands? They found seven.

The Failure Celebration

This one’s counterintuitive, but crucial. When a solution doesn’t work, we literally say, “Great! We found one way that doesn’t work. What should we try next?” My daughter now announces her failures with pride: “Dad! My idea totally flopped! But I have another one!”

Your Three Steps This Week

Step 1: Choose Your Challenge Zone

Pick one area where you typically solve problems for your child. Maybe it’s opening stubborn jar lids, fixing minor toy breaks, or dealing with tangled shoelaces. This week, make that your “figure it out together” zone.

Why it matters: Kids need predictable opportunities to practice, and you need a comfortable starting point.

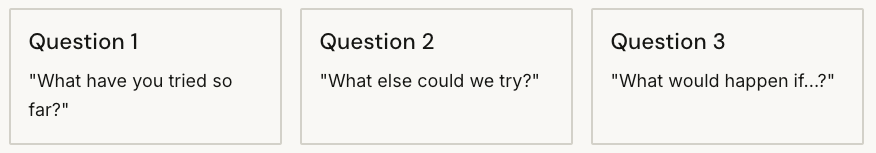

Step 2: Master the Magic Questions

Instead of giving solutions, ask: “What have you tried so far?” “What else could we try?” “What would happen if…?” Write these on a sticky note if needed.

Why it matters: Questions teach thinking patterns that last forever, while solutions only solve today’s problem.

Step 3: Create a Problem-Solving Victory Wall

This weekend, set up a simple space (even just a piece of paper on the fridge) where kids can document problems they’ve solved. Draw pictures, write short descriptions, whatever works. My son drew a cartoon of himself defeating the “Evil Zipper Monster.”

Why it matters: Visible victories build problem-solving identity. Kids start seeing themselves as people who figure things out.

The Future We’re Building, One Stuck Lid at a Time

That Tuesday with the water bottle feels like last week, but I can already see changes in my daughter.

Yesterday, when her art project fell apart, she didn’t call for help. I watched from the doorway as she examined the damage, tried three different fixes, and finally created something even better than her original plan.

“Dad!” she called out eventually. “Come see what I problem-solved!”

Not “fixed.” Not “made.” Problem-solved. She’s claimed that identity now.

Here’s my promise to you: I’m not raising kids who never encounter problems. I’m raising kids who see problems as puzzles, not catastrophes. Kids who know that every stuck lid, broken toy, and tangled mess is actually a gift—a chance to grow the mental muscles they’ll need for whatever comes next.

And honestly? I think that’s the most important thing we can teach them. Because while we can’t predict the problems they’ll face in 2035 or 2040, we can make sure they face them with confidence, creativity, and maybe even a little excitement.

LEAVE A COMMENT