The Day My Daughter’s Science Project Flopped (And Why Her Response Made Me Prouder Than Any A+ Could)

My 10-year-old daughter spent three weeks building a volcano for her science fair.

Not just any volcano. An elaborate, carefully researched, meticulously painted masterpiece. She watched YouTube tutorials. She measured baking soda ratios. She practiced the eruption timing twelve times in our backyard.

The morning of the fair, she woke up at 6 AM to do one final practice run.

The volcano didn’t erupt. Just… sat there. Silent. A painted mountain doing nothing.

She tried again. Nothing. Checked her measurements. Tried a third time. Still nothing.

I watched her face crumble. Tears started. We had twenty minutes before we needed to leave for school.

Here’s what broke my heart: Her first instinct wasn’t to troubleshoot or try a different approach. It was to say, “I can’t do this. I’m not going to school. Everyone’s project will work and mine won’t.”

She was ready to give up completely because of one setback.

And that’s when I realized: We’d taught her to work hard. We’d taught her to plan ahead. But we have not taught her what to do when hard work doesn’t guarantee success.

The Problem: Schools Reward Success, Not Recovery

Here’s what schools teach our kids about failure:

Get good grades = success. Get bad grades = failure. There’s no in-between. There’s just a letter on a report card that becomes part of their permanent record.

So kids learn to avoid failure at all costs.

They stop trying new things because “what if I’m not good at it?” They quit activities the moment they’re not immediately successful. They hide mistakes instead of fixing them. They see failure as an ending, not a beginning.

But here’s what life actually requires:

- Trying something new and being terrible at it

- Making mistakes in front of people

- Getting rejected and bouncing back

- Failing publicly and trying again anyway

- Learning that failure is information, not identity

Every successful entrepreneur fails constantly. Every artist creates bad work before good work. Every athlete loses games. Every adult reading this has failed dozens of times this year alone.

The difference between people who succeed long-term and people who give up? It’s not talent. It’s not intelligence. It’s how they respond to failure.

And nobody is teaching our kids this skill.

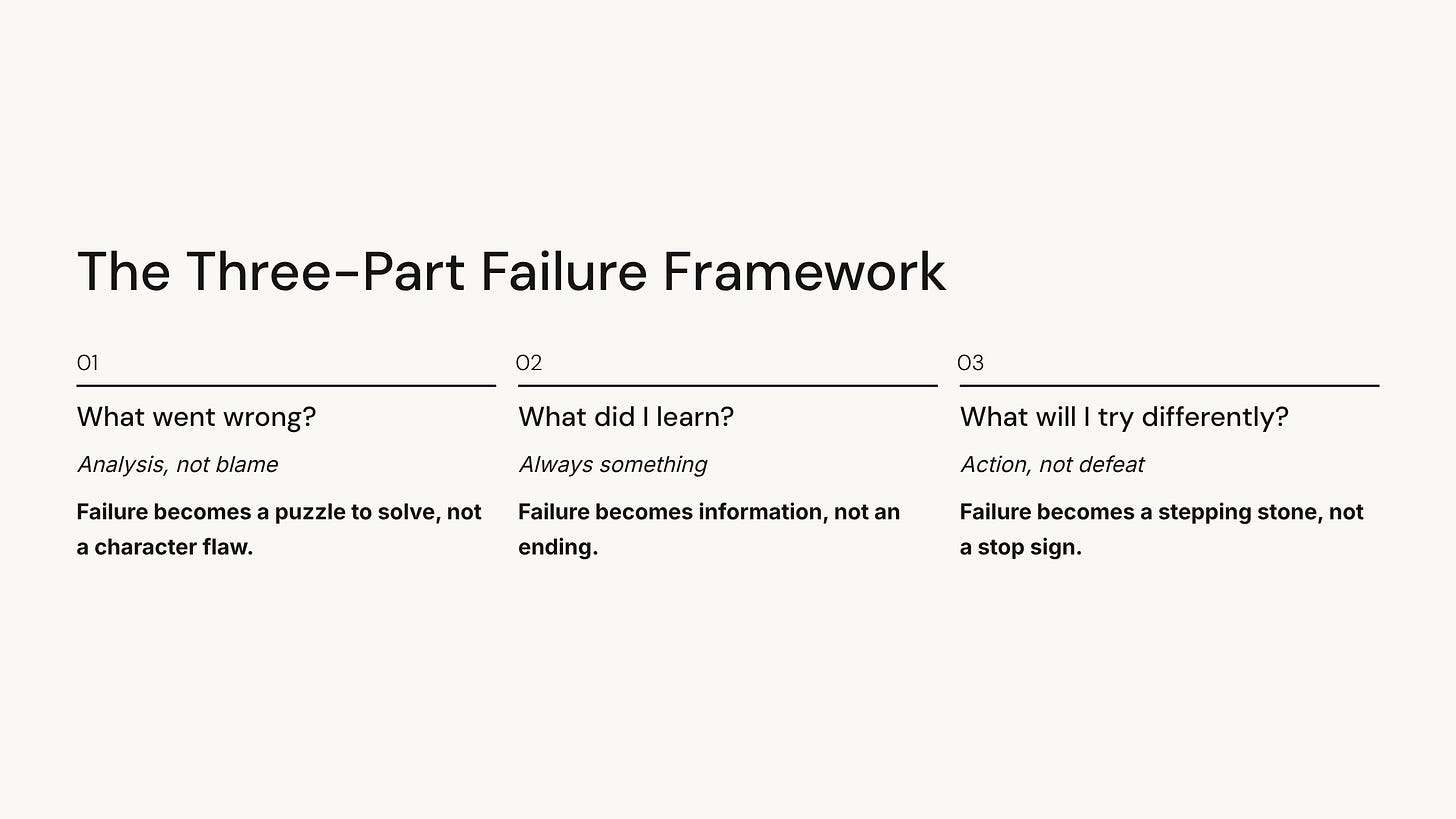

What Actually Works: The Three-Part Failure Framework

After my daughter’s volcano disaster, I developed a simple system for teaching kids to handle failure. It’s based on three questions that reframe failure from devastating to useful:

1. “What went wrong?” (Analysis, not blame)

This teaches kids to look at failure objectively. Not “I’m stupid” or “I’m bad at science.” But “The baking soda measurement was off” or “I didn’t account for humidity.”

Failure becomes a puzzle to solve, not a character flaw.

2. “What did I learn?” (Always something)

This is the hardest question because kids’ first instinct is “nothing, I just failed.” But there’s always learning. Maybe they learned this method doesn’t work. Maybe they learned they need to test earlier. Maybe they learned to ask for help sooner.

Failure becomes information, not an ending.

3. “What will I try differently?” (Action, not defeat)

This moves them from analysis to action. Not “I’ll try harder” (vague and unhelpful). But specific changes: “I’ll do a practice run the day before, not the morning of” or “I’ll have a backup plan.”

Failure becomes a stepping stone, not a stop sign.

That morning with the volcano, I sat with my daughter and walked her through these three questions. It took seven minutes.

Her answers:

- What went wrong? “I think the baking soda got damp overnight.”

- What did I learn? “I should test it the night before, not the morning of. And have backup supplies.”

- What will I try differently? “Can we go to the store right now and get fresh baking soda?”

We did. She tested it in the car while I drove. It worked.

Her volcano erupted perfectly at the science fair. But that’s not the part that made me proud.

The Result That Changed Everything

Three weeks later, my daughter tried out for the school play. Lead role. She practiced for weeks.

She didn’t get the part. Not even a minor role. The teacher assigned her to backstage crew.

She came home disappointed. I braced myself for tears and “I’m quitting.”

Instead, she said: “I think I went too big too fast. I should have tried for a smaller part first to learn how auditions work. Next time I’m going to practice in front of people before the real audition. And I’m going to do crew this year so I can see what the leads do up close.”

I almost cried.

She’d used the framework on her own. Without prompting. Failure had become information, not identity.

She worked crew for the spring musical. Watched the leads rehearse. Asked questions. Learned stage presence. Built relationships with the drama teacher.

The next audition, she auditioned again. Different approach. Smaller role request. Better preparation.

She got it.

But more importantly: She’d learned that failure is just the first draft of success.

Because the truth is: The kids who learn to handle failure will outperform the kids who never fail. Every time.

LEAVE A COMMENT