When to Move Forward: The Observable Markers of Mathematical Mastery

Your child just finished Week 3 of addition within 20. The curriculum guide says it’s time to move to subtraction strategies.

But something feels off. Your child solved the problems, used the manipulatives correctly, and seemed engaged. Yet you’re not confident they’re ready.

Should you move forward because the calendar says so? Or stay longer because your instinct says they need more time?

This is the question that determines whether your manipulative math curriculum builds deep understanding or creates a shaky foundation that crumbles in third grade.

The answer isn’t in the curriculum guide. It’s in what you observe when your child works.

Why “Finishing the Lessons” Doesn’t Mean Ready

Traditional curricula train us to think: completed lessons = mastery.

You worked through pages 23-35. Your child got most problems correct. Time to move to pages 36-48.

This works if you’re teaching procedures. It fails catastrophically if you’re building conceptual understanding.

Here’s what actually happens when you move forward based on completion rather than mastery:

Your second grader “finishes” place value. Builds numbers with base-ten blocks accurately. Moves to addition with regrouping.

Then suddenly can’t add 47+28. Not because addition is hard, but because their place value understanding was surface-level. They could follow steps but didn’t deeply understand tens and ones as quantities.

Now you’re backtracking. Or pushing through with confusion. Or assuming “they’re just not good at math.”

The problem wasn’t the child. It was moving forward before the foundation solidified.

Montessori observed this pattern repeatedly: Children need time to internalize concepts through repeated experience, not just one-time exposure. The normalization period—when a child can work independently and confidently with a concept—is what signals readiness for complexity.

Froebel called it “making the outer inner”—the physical manipulation must become mental understanding before abstraction makes sense.

You can’t rush this process by completing more pages.

The Three Levels of Mathematical Understanding

When you’re deciding whether to move forward, you’re actually assessing which level of understanding your child has reached.

Level 1: Procedural (following steps)

Your child can solve problems if:

- Manipulatives are present

- You’re sitting nearby

- You occasionally prompt: “What do you do next?”

- The problem type is familiar

They’re following a procedure you’ve taught. This looks like understanding, but it’s actually imitation.

Test: Present a slightly different problem format or use different manipulatives. Does your child know what to do?

If no—they’re at Level 1. Not ready to move forward.

Level 2: Conceptual (understanding why)

Your child can:

- Solve problems with manipulatives independently

- Explain what they’re doing: “I’m making a group of 10 because…”

- Choose appropriate manipulatives without being told

- Solve the problem a different way if asked

- Identify when they’ve made an error

They understand the concept, not just the steps.

Test: Ask “Why does that work?” or “Show me a different way.” Can they explain or demonstrate?

If yes—they’re at Level 2. Almost ready to move forward.

Level 3: Transferable (applying independently)

Your child can:

- Solve problems without manipulatives for familiar situations

- Recognize when a new problem relates to known concepts

- Apply the concept in real-world situations unprompted

- Teach the concept to someone else

- Create their own problems

The concept has become flexible mental knowledge.

Test: Present a real-life situation without saying “this is a math problem.” Does your child recognize the mathematical opportunity and apply appropriate thinking?

If yes—they’re at Level 3. Ready to move forward.

The key insight: Level 1 takes days. Level 2 takes weeks. Level 3 takes months of application.

Most curricula move you forward at Level 1. You need to stay until Level 2, and ideally see signs of Level 3 emerging.

Observable Markers: What to Watch For

Stop asking “Did they finish the lessons?” Start watching for these specific behaviors.

Marker 1: Decreasing Reliance on Manipulatives

What it looks like:

Early in learning (Level 1): Your child reaches for manipulatives immediately. Counts every block, one by one. Needs to physically act out every problem.

Moving toward mastery (Level 2): Your child hesitates before taking manipulatives. Sometimes solves mentally, then checks with blocks. Uses manipulatives for complex problems but not simple ones.

At mastery (Level 3): Your child works mentally or with quick drawings for most problems. Reaches for manipulatives only for challenging problems or to verify unusual situations.

Important: This progression takes weeks to months, not days. Don’t rush it.

Your kindergartener learning addition within 10 might need manipulatives for every problem for two months.

Then suddenly, over two weeks, you’ll notice them solving 3+2, 4+1, 5+5 mentally while still using blocks for 6+7.

That’s normal progression. Not a sign they “should” be past manipulatives already.

What to do:

- Keep manipulatives available even after mental strategies emerge

- Notice which problems your child solves mentally (usually smaller numbers or doubles)

- Don’t push mental math before they’re ready—let it emerge naturally

- Celebrate both manipulative solutions and mental solutions equally

Marker 2: Accurate Self-Correction

What it looks like:

Early learning: Your child makes an error, doesn’t notice, and continues. You point out the mistake. They fix it with your guidance.

Moving toward mastery: Your child makes an error, you stay silent, and they notice: “Wait, that doesn’t look right.” They recheck their work and fix it without you identifying the specific error.

At mastery: Your child catches errors while working, not just at the end. They’ve internalized what “correct” looks and feels like.

This marker is huge. It shows internal understanding, not just external compliance.

When your child can evaluate their own work against an internal standard of correctness, they own the mathematics. It’s not just your knowledge they’re borrowing.

What to watch for:

- Child recounts manipulatives without being asked

- Child says “that can’t be right” before you say anything

- Child checks answer a different way spontaneously

- Child compares their result to an estimate: “I thought it would be about 30, and I got 28, so that makes sense”

What to do:

- Build in wait time—don’t immediately correct errors

- Ask “Does that answer seem reasonable to you?” before pointing out mistakes

- When you do identify errors, ask “How could you check that?” rather than “That’s wrong”

- Celebrate self-correction enthusiastically: “You caught that yourself! That’s mathematical thinking.”

Marker 3: Multiple Solution Strategies

What it looks like:

Early learning: Your child has one way to solve a problem (usually the way you showed them). If that doesn’t work, they’re stuck.

Moving toward mastery: When asked “Can you solve it a different way?” your child can demonstrate an alternative method.

At mastery: Your child spontaneously uses different strategies for different problems. They choose efficient strategies based on the numbers involved.

Example with 9+7:

Level 1 child: Counts all (counts 9, then counts 7, then counts the combined pile)

Level 2 child: Can demonstrate multiple ways when you ask:

- Make 10: 9+1=10, then 10+6=16

- Count on: Start at 9, count up 7 more

- Use doubles: 8+8=16, so 9+7 is one less

Level 3 child: Looks at 9+7 and says “I’ll make 10 because 9 is close to 10” without you suggesting it. Then looks at 5+6 and says “I’ll use doubles—it’s close to 5+5.”

What this tells you:

When children have multiple strategies, they understand the concept flexibly. They’re not locked into one procedure.

This is especially critical in mathematics. The most powerful mathematical thinkers aren’t the ones who know the most formulas—they’re the ones who can see problems from multiple angles.

What to do:

- Regularly ask: “Show me another way”

- Demonstrate multiple strategies yourself

- Celebrate variety: “I love that you solved it differently than yesterday”

- Create strategy discussion: “Which way was easier? Why?”

Marker 4: Explaining Without Prompting

What it looks like:

Early learning: You ask: “How did you get that answer?” Your child: “I don’t know. I just did it.”

Moving toward mastery: You ask: “How did you figure that out?” Your child: Explains clearly with mathematical language: “I made groups of 5 because it’s easier to count by 5s.”

At mastery: Your child explains their thinking without being asked: “I used the ten frame and made 10 first because 8 is close to 10.”

Why this matters:

Mathematics is a language. Children who can articulate mathematical thinking can manipulate mathematical ideas mentally.

When your child can explain their reasoning, they’re thinking about their thinking (metacognition). This is the foundation for all higher-level mathematics.

Conversely, children who can calculate but not explain are following procedures without understanding. They’ll struggle when problems get more complex.

What to listen for:

- Use of mathematical vocabulary: “I regrouped,” “I made equal groups,” “I partitioned the shape”

- Cause-and-effect language: “I did ___ because ___”

- Comparisons: “This is like when we…” or “This is different from…”

- Reasoning: “It has to be ___ because…”

What to do:

- Ask “How did you know?” and “Why does that work?” regularly

- Give wait time for explanations—good explanations take thinking time

- Model mathematical explanation yourself: “I’m going to solve this problem. Watch how I think about it…”

- Accept approximate language initially, gradually refine to mathematical precision

Marker 5: Application Without Instruction

What it looks like:

Early learning: You present a word problem. Your child asks: “Is this addition or subtraction?”

They can’t identify the operation without your guidance.

Moving toward mastery: You present a word problem. Your child reads it, chooses manipulatives, and solves without asking what to do.

At mastery: Your child encounters a situation in real life and applies mathematics without you framing it as a math problem.

“Mom, if we need cookies for 4 friends and each friend gets 3 cookies, we need 12 cookies total.”

You didn’t ask them to solve anything. They recognized the mathematical structure and solved it.

This is the ultimate marker. Mathematics has transferred from “school subject” to “thinking tool.”

Real examples:

Kindergartener: Notices pattern in floor tiles and extends it verbally: “Blue, blue, white, blue, blue, white…”

Second grader: Setting the table for 5 people, counts out forks by 5s: “5, 10, 15, 20, 25. We need 25 forks.”

Fourth grader: Sees recipe serves 4, you’re cooking for 6. Says unprompted: “We need to make 1.5 times the recipe.”

What to watch for:

- Child uses mathematical language outside math time

- Child solves problems without being told it’s a problem

- Child makes mathematical observations: “This box is bigger because…”

- Child creates mathematical challenges: “I wonder how many blocks tall our doorway is?”

What to do:

- Notice and acknowledge: “You just used multiplication thinking!”

- Create opportunities: cooking, measuring, building, shopping

- Don’t over-praise or make it a big deal—just acknowledge naturally

- Answer mathematical questions mathematically, extending their thinking

The Assessment Conversation: How to Actually Determine Readiness

You’ve been working on a concept for 1-3 weeks. Time to decide: move forward or stay longer?

Here’s the conversation that tells you.

Sit down with your child and their manipulatives. No curriculum, no specific problems prepared.

Say this: “Show me [concept] like I’m someone who’s never seen it before. Teach it to me.”

Then watch and listen.

If they can:

- Demonstrate the concept with manipulatives clearly

- Explain each step as they go

- Answer your “Why?” questions

- Show you an example problem from start to finish

- Recover if they make a mistake

They’re ready to move forward.

If they:

- Struggle to start without a specific problem

- Can demonstrate but not explain

- Need you to prompt each next step

- Can’t answer “Why does that work?”

- Get frustrated or give up quickly

They need more time with this concept.

Example: Assessing place value understanding

You: “Teach me about tens and ones like I don’t know anything about them.”

Ready to move forward response: Child: “Okay, so numbers are made of tens and ones. This rod is a ten—it’s 10 little cubes stuck together. These little cubes are ones. If I want to make 47, I use 4 tens—that’s 40—and 7 ones. See? 40 plus 7 is 47. I can show you with different numbers too.”

Needs more time response: Child: “Um… these are blocks. You put them together. Like this? Is that right?”

The difference is obvious when you actually have the conversation.

Do this assessment every 1-2 weeks for major concepts. Don’t wait until you’ve “finished” all the planned lessons.

If your child demonstrates mastery in week 2 of a 4-week plan, move forward. If they’re not there by week 4, stay longer.

The curriculum serves your child. Your child doesn’t serve the curriculum.

When to Definitely Stay Longer (Even If the Calendar Says Move On)

Some situations make the decision clear:

Stay longer if:

1. Your child needs heavy prompting for every problem

If you’re essentially solving the problems by asking leading questions, they’re following your thinking, not doing their own.

Stay until they can work through familiar problem types with minimal input from you.

2. Manipulative use is inefficient

Your child uses manipulatives but counts by ones every time. Doesn’t group. Doesn’t use patterns or shortcuts.

Example: To solve 8+5, they count out 8 individual blocks, then 5 individual blocks, then count the entire pile from 1-13.

They’re using manipulatives but not using them mathematically. They haven’t internalized grouping, patterns, or efficient strategies.

Stay longer and explicitly teach more efficient use: “Can you show me 8 on the ten frame? Now what happens when we add 5?”

3. Similar problems produce inconsistent results

Your child solves 7+5 correctly with manipulatives. Two minutes later, solves 6+5 incorrectly.

This inconsistency means they don’t have a reliable mental model yet. They’re guessing their way through, sometimes successfully.

Stay longer. Do more problems. Build confidence and consistency.

4. Your child can’t explain why their answer is right

If the only defense of an answer is “Because that’s what I got,” understanding is shallow.

Mathematical reasoning is always “I got ___ because ___.”

Stay longer and build the explaining muscle.

5. Interest has completely evaporated

If your child used to engage willingly and now resists every session, something’s wrong.

Either:

- The concept is too difficult (understanding isn’t there)

- The concept is too easy (they’re bored with repetition)

- The pacing is wrong

- They need a break from formal math

Stay with the current concept but change the approach. Use games. Use real-world application. Take a week off and return fresh.

Don’t push forward hoping the next concept will re-engage them. Fix the engagement problem first.

When to Definitely Move Forward (Even If You Feel Uncertain)

Sometimes you second-guess yourself and keep a child at a concept longer than needed.

Move forward if:

1. Your child is solving problems before you finish explaining them

If they hear the beginning of a problem and jump to solve it correctly without needing to hear the rest, they’ve mastered the pattern.

Staying longer becomes busywork, not learning.

2. Your child creates variations independently

“I made a harder problem for myself: 18+35!”

This shows they understand the concept well enough to extend it. They’re ready for actual harder problems.

3. Your child explains the concept to siblings or friends unprompted

Teaching is evidence of deep understanding.

If your child is teaching others, they’ve internalized the concept.

4. Problems are solved mentally without manipulatives reaching for

If manipulatives are on the table but unused for several consecutive days, the mental models have formed.

Time to move to more complex applications where manipulatives will be useful again.

5. You observe application in daily life repeatedly

If you’ve noticed your child using the mathematical concept in 3+ real-world situations unprompted, transfer has happened.

This is Level 3 understanding. Move forward confidently.

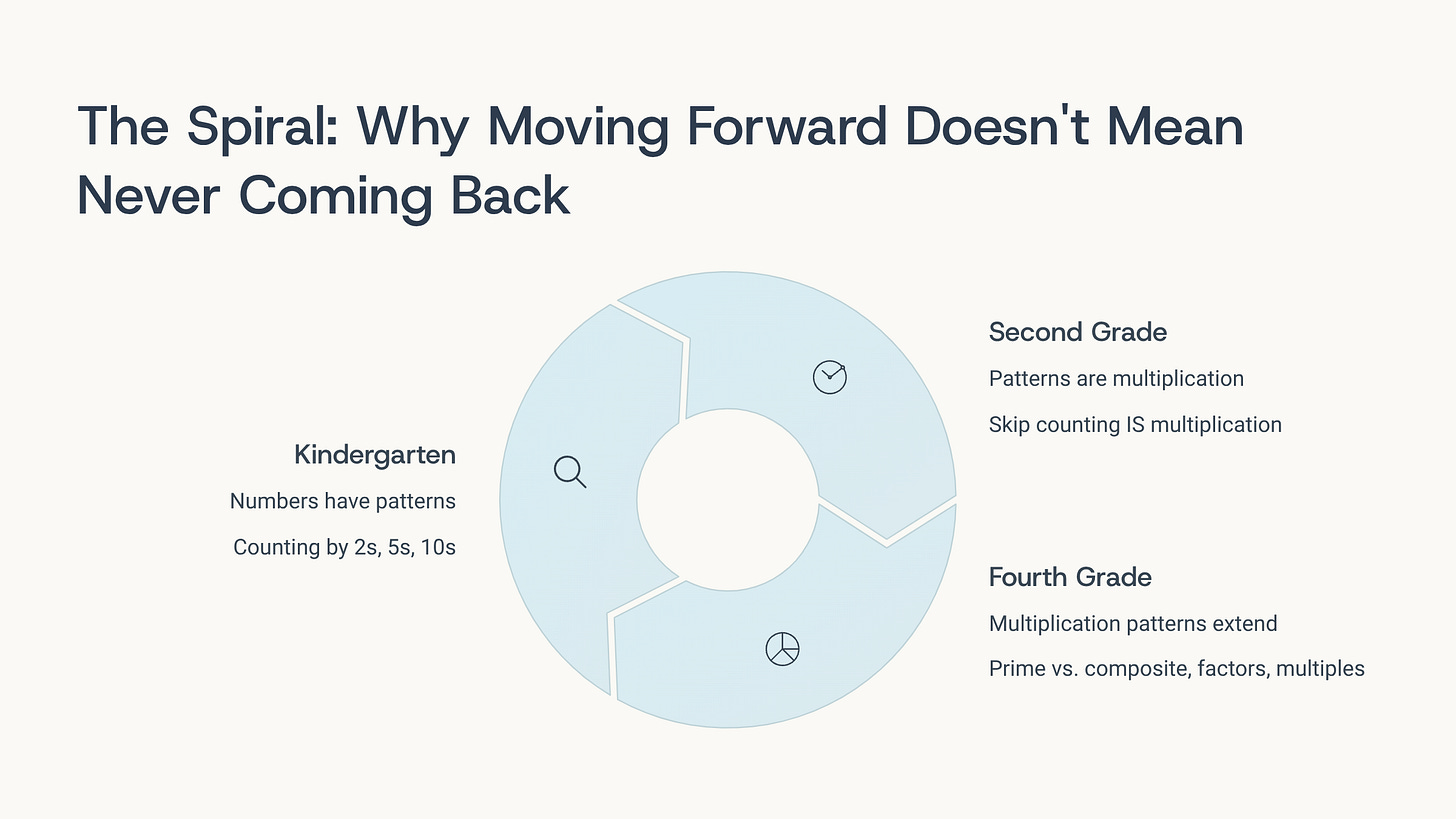

The Spiral: Why “Moving Forward” Doesn’t Mean “Never Coming Back”

Here’s what relieves the pressure of this decision:

You’re not asking: “Has my child learned place value forever?”

You’re asking: “Has my child learned place value well enough for this level, so we can revisit it at greater depth later?”

Mathematical learning spirals. You encounter concepts multiple times with increasing sophistication.

Your kindergartener learns: Numbers have patterns (counting by 2s, 5s, 10s).

Your second grader learns: These patterns are multiplication (skip counting IS multiplication).

Your fourth grader learns: Multiplication patterns extend (prime vs. composite numbers, factors, multiples).

Same core concept. Different depth each time.

This means: It’s okay to move forward before absolute perfection. You’ll return to this concept.

But: You need solid understanding at each level before the next level makes sense.

Your second grader can’t understand multiplication if they don’t understand counting patterns.

Your fourth grader can’t understand factors if they don’t understand multiplication.

So the question becomes:

“Is my child’s understanding solid enough to support the next level when we return to this concept?”

Not: “Have they achieved final mastery?”

This reframes everything. You’re not pursuing perfection. You’re pursuing adequate foundation.

Creating Your Personal Mastery Checklist

The curriculum guide gives you general timelines. You need specific markers for YOUR child and THIS concept.

Before you start teaching a concept, create a simple checklist:

Concept: [e.g., Addition within 20 using make-10 strategy]

I’ll know my child is ready to move forward when they can:

□ Demonstrate make-10 strategy with manipulatives (ten frames, counters) without prompting

□ Explain why making 10 first is helpful (”because 10 is easy to add to”)

□ Solve 5+ problems using this strategy with 90%+ accuracy

□ Choose when to use make-10 vs. other strategies based on numbers (9+7 yes, 4+3 no)

□ Solve at least 3 make-10 problems mentally without manipulatives

□ Teach this strategy to someone else clearly

Optional (signals deep mastery): □ Apply this thinking in different context (making 100, making dollar) □ Create own make-10 problems □ Recognize when someone else uses this strategy

Write this checklist at the start of the concept. Check off items as you observe them. When you have the first 5-6 checked, move forward.

This removes emotion from the decision. You’re not guessing. You’re observing against predetermined criteria.

The Practical Weekly Check-In

You don’t need formal assessment. You need observant teaching.

Every Friday (or end of your week), spend 10 minutes:

1. Review the week’s concept Ask your child: “What did you learn about [concept] this week?”

Their explanation tells you their mental model.

2. Give a novel problem Not from the curriculum. Not one they’ve practiced.

A problem that requires applying the concept in a slightly new way.

Their approach tells you transferability.

3. Ask for self-assessment “How do you feel about [concept]? Does it make sense? What’s still tricky?”

Children often know when they’re shaky. Listen to them.

4. Make your decision Based on your observations this week, mastery markers, and Friday check-in:

- Move forward

- Stay another week

- Stay but adjust approach (more games, different manipulatives, slower pace)

- Take a break and return

Document your decision. Brief note: “2/15: Stayed extra week with place value—still counting by ones, not using rods efficiently.”

This creates a record of your child’s learning pace that informs future decisions.

What This Looks Like in Real Time

Week 1 with new concept:

- Expect Level 1 understanding

- Heavy manipulative use, heavy parent support

- Mistakes are normal, confusion is normal

- Success marker: Child can follow the procedure with guidance

Week 2:

- Watch for emerging Level 2 understanding

- Less reliance on your prompting

- Beginning to explain, not just demonstrate

- Some problems solved efficiently

Week 3:

- Most children reach Level 2 here for grade-appropriate concepts

- Manipulative use is efficient and purposeful

- Clear explanations

- Self-correction emerging

- Decision point: Move forward or stay one more week

Week 4 (if you stayed):

- See Level 3 markers emerging

- Mental strategies appearing

- Real-world application

- Ready to move forward

Some children need 6 weeks. Some need 2 weeks. Both are normal.

Fast isn’t better. Slow isn’t worse. Matched to readiness is what matters.

When Your Gut and the Markers Disagree

Sometimes your observation says “ready” but your instinct says “not quite.”

Trust your instinct if:

- You’re with this child daily—you know things formal markers can’t capture

- There’s been recent disruption (new baby, move, illness) affecting focus

- Your child has learning differences that don’t show up in standard markers

- The concept is foundational for the next 3 concepts (place value, fraction understanding, etc.)

Trust the markers if:

- You tend toward perfectionism or anxiety about your child’s progress

- You’re comparing to other children or grade-level standards

- You’re worried about “falling behind”

- Your child is demonstrating mastery but you want more practice just to be sure

The balance: Objective observation plus parental knowledge equals good decisions.

Your Next Step: Start Watching Differently

This week, during your math time, watch for one specific marker.

Choose from:

- Decreasing manipulative reliance

- Self-correction

- Multiple strategies

- Explaining thinking

- Real-world application

Just one. Watch for it intentionally.

When you see it, note it. “Tuesday: Used mental math for 4+5 without reaching for blocks first.”

By Friday, you’ll have a clearer picture of where your child actually is with the current concept.

That clarity makes the decision—stay or move—obvious.

You’re not teaching blindly anymore. You’re teaching responsively, matching pace to actual understanding.

This is how manipulative math builds the deep foundation that supports all future learning.

Not by completing lessons.

By building mastery.

LEAVE A COMMENT