When to Stop Using Manipulatives (And Why Most Parents Stop Too Soon)

Your eight-year-old has been using blocks to solve addition problems for six months. She’s confident, accurate, and understands what she’s doing.

Last week, your mother-in-law watched a math lesson and pulled you aside afterward. “She’s still using those toys? Don’t you think it’s time she learned to do it in her head like a normal kid?”

Now you’re second-guessing yourself. Maybe you’re creating a crutch. Maybe she should be past this by now. Maybe manipulatives are for little kids, and you’re holding her back.

Here’s what’s actually happening: You’re doing exactly the right thing, and stopping now would be the mistake.

The pressure to abandon manipulatives too early is one of the most damaging forces in math education. It comes from well-meaning relatives, comparison with traditionally-schooled kids, and our own anxiety that we’re somehow “behind.”

But here’s what 150 years of educational research tells us: Children don’t outgrow the need for concrete representation—they expand their ability to work with increasingly abstract representations while maintaining concrete understanding as their foundation.

Let me show you what this actually means for your homeschool math lessons.

The Concrete-Abstract Continuum (Not a Ladder)

Most people think about manipulatives like training wheels—something you use until you’re ready for the “real thing,” then discard forever.

This metaphor is completely wrong and explains why so many kids struggle with math.

Mathematicians use concrete representations their entire careers. They draw diagrams. They build models.

They use physical objects to explore new concepts before moving to symbolic notation. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman was famous for his stick-figure drawings that made complex physics concepts tangible.

The goal isn’t to stop using concrete materials. The goal is to develop fluency across multiple representations so your child can move between concrete, pictorial, and abstract as needed.

Here’s what this looks like in practice:

A nine-year-old working on multiplication encounters 7×8. She:

- Can solve it with objects (arranging 7 rows of 8 items)

- Can draw an array on paper if she needs to

- Can visualize the array mentally and solve it

- Can recall it automatically from memory

She has all four tools available. For easy facts, she uses memory. For challenging problems, she drops back to visualization or drawing. For completely new concepts, she reaches for physical objects.

This isn’t regression—this is mathematical maturity.

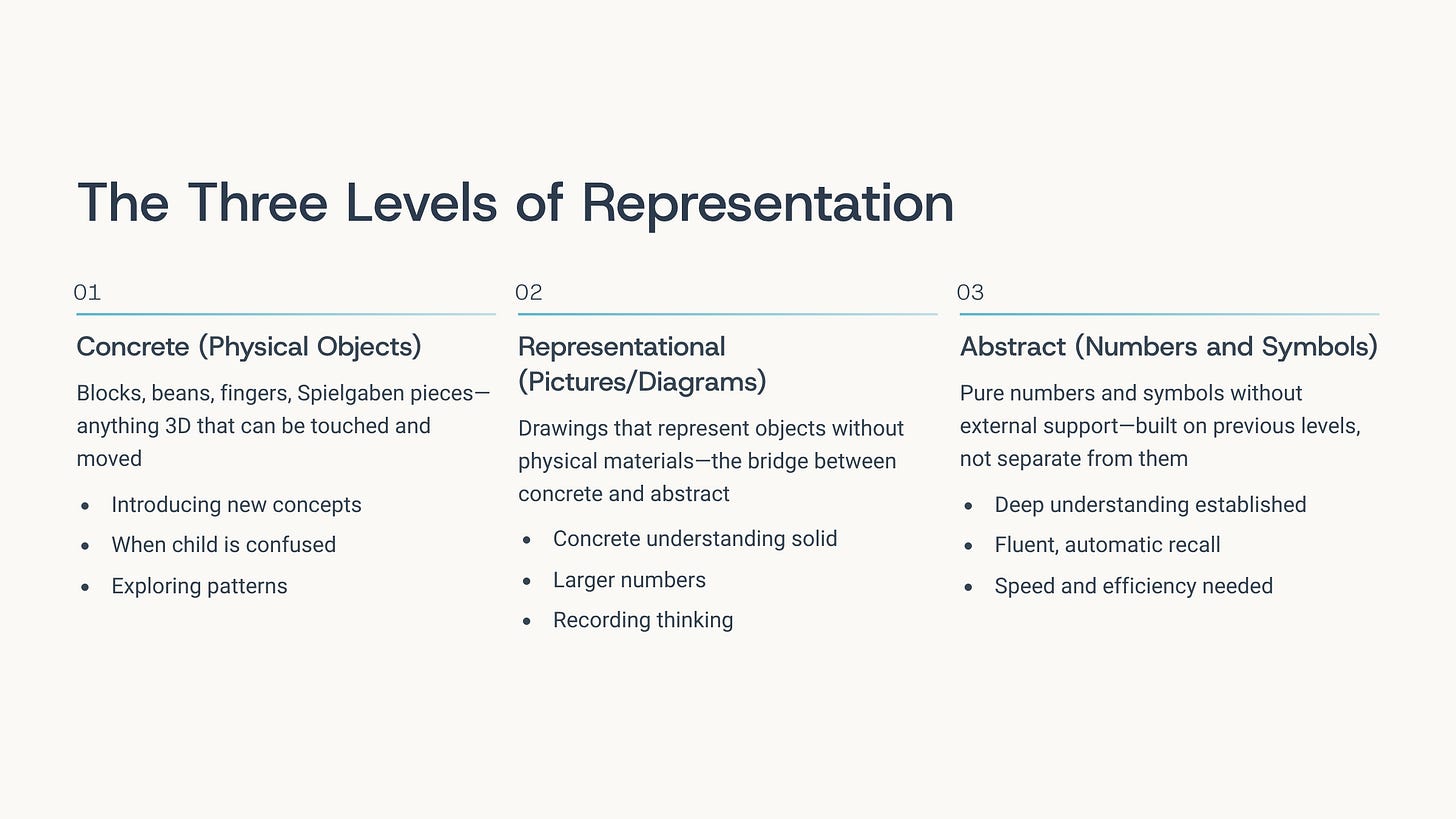

The Three Levels of Representation

Before we talk about when to transition, you need to understand what you’re transitioning through.

Level 1: Concrete (Physical Objects)

Your child physically manipulates actual objects. Blocks, beans, fingers, Spielgaben pieces, Cuisenaire rods—anything three-dimensional that can be touched, moved, and counted.

This is where understanding is built. This is not the “baby” level—this is the foundation level, and your child will return here for every new concept she learns through high school.

When to use it:

- Introducing any new concept

- When a child is confused or stuck

- When moving to a higher level isn’t working yet

- When exploring patterns or relationships

Level 2: Representational (Pictures/Diagrams)

Your child draws pictures or diagrams that represent the objects without needing the actual physical materials. These might be detailed drawings at first, then progress to simple marks, tallies, or symbolic representations.

This is the bridge between concrete and abstract. It’s not a brief stop-over—children spend considerable time here, and that’s developmentally appropriate.

When to use it:

- When concrete understanding is solid but abstract isn’t yet

- For larger numbers that are cumbersome with objects

- To record thinking for later reference

- When physical materials aren’t available

Level 3: Abstract (Numbers and Symbols)

Your child works purely with numbers, symbols, and mental representations without needing external support.

This is the final form, but it’s built on the other two levels, not separate from them. A child who reaches this level without solid concrete foundation will struggle as concepts increase in complexity.

When to use it:

- When the concept is deeply understood at previous levels

- For fluent, automatic recall (basic facts)

- When speed and efficiency matter

- For problems that don’t require new conceptual understanding

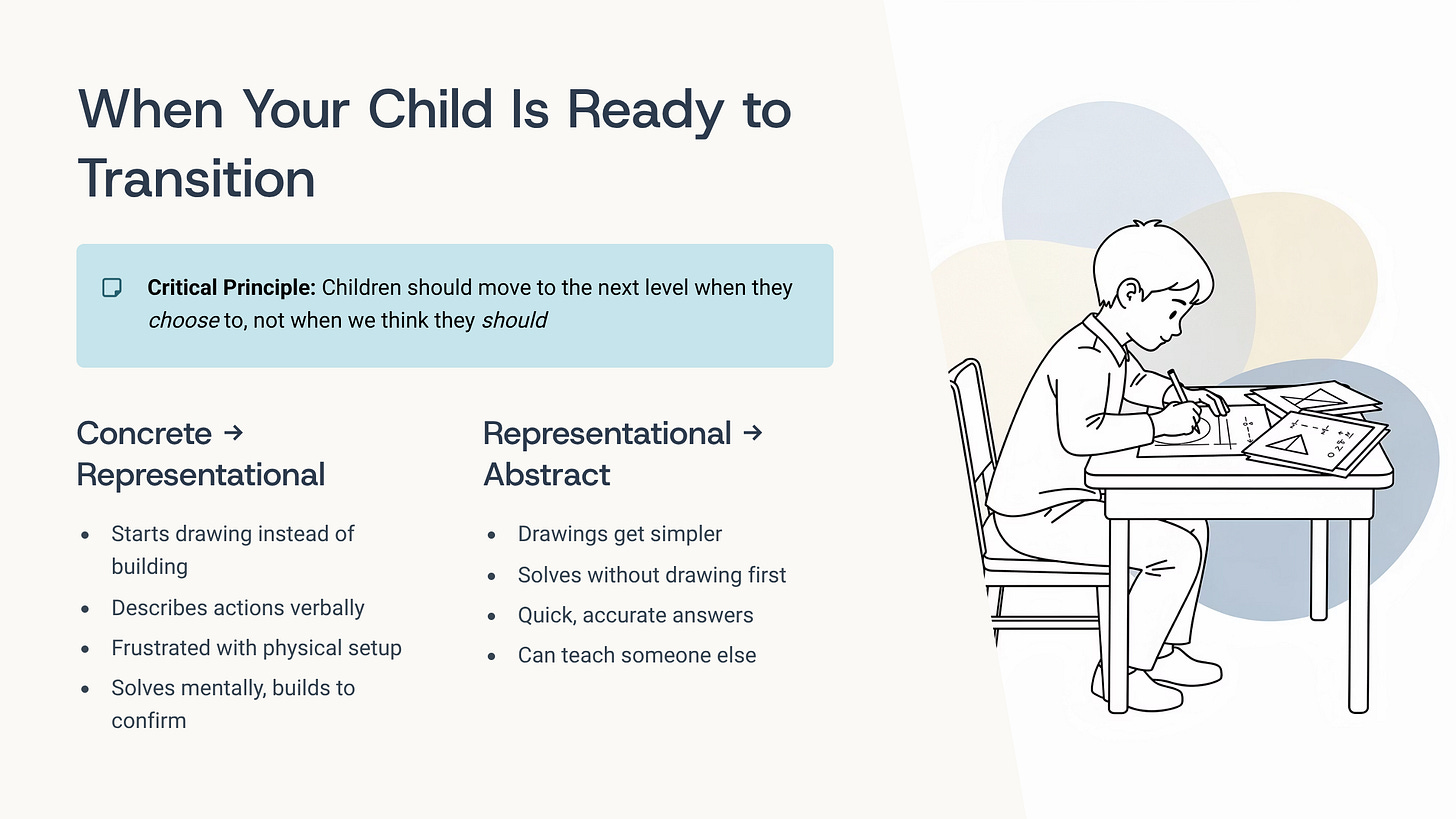

How to Know When Your Child Is Ready to Transition

Here’s the critical principle: Children should move to the next level when they choose to, not when we think they should.

Watch for these specific signs that your child is ready to move from concrete to representational:

She starts drawing instead of building: You give her the blocks, and she sketches an array on paper instead. She’s showing you she can visualize the concrete form and doesn’t need to physically manipulate it anymore.

She describes what she’s doing: “I’m putting these 6 into groups of 2…” She’s verbalizing the concrete action, which shows she’s internalizing the process.

She gets frustrated with the physical setup: “This is taking too long. Can I just draw it?” This is efficiency-seeking, not laziness—a sign of readiness.

She solves it mentally, then builds to confirm: She’s using concrete materials for verification, not primary solution. This shows the mental model is forming.

Watch for these signs your child is ready to move from representational to abstract:

Her drawings get simpler: Instead of detailed pictures, she makes quick marks, tallies, or abbreviations. She’s compressing the representation because she doesn’t need the full detail anymore.

She solves without drawing, then adds the drawing afterward: The picture becomes documentation, not process.

She gets the answer quickly and accurately: And when you ask “how did you do that?” she can explain her thinking clearly.

She can teach someone else: She can explain the concept without materials, using words and gestures.

The Mistake That Ruins Everything: Forcing Transition Too Early

You’ll know you’ve pushed abstraction too soon when you see these warning signs:

Your child gets the right answer but can’t explain why. She’s memorized a procedure without understanding. This will collapse as soon as the problems get more complex.

Simple variations confuse her. She can solve 24÷6 but gets stuck on 6×?=24. She doesn’t see these as the same relationship because she never built concrete understanding.

She’s slow and uncertain even with “easy” problems. She’s counting on fingers for addition facts she “learned” two years ago. The abstract symbols never connected to quantity.

Math anxiety appears or intensifies. She’s working with symbols she doesn’t understand, and it feels like memorizing arbitrary rules. This is psychologically overwhelming.

She says “I hate math” or “I’m not good at math.” This is a child who’s been pushed to abstraction before she was ready, and now math feels like failure.

If you see any of these signs, go back to concrete materials immediately. This isn’t moving backward—this is building the foundation that should have been built first.

Age Guidelines (That You Should Mostly Ignore)

Here are extremely rough guidelines for when children typically develop comfort at each level. But please remember: these are averages, not rules. Your child’s timeline might be completely different, and that’s fine.

Kindergarten-1st Grade (ages 5-7):

- Primarily concrete

- Beginning to use simple pictures to show their thinking

- Abstract work limited to very small numbers (1-10) with concrete foundation

2nd-3rd Grade (ages 7-9):

- Comfortable moving between concrete and representational

- Beginning to work abstractly with concepts they deeply understand

- Still returning to concrete for all new concepts

4th-5th Grade (ages 9-11):

- Often prefer representational or abstract for routine work

- Reach for concrete materials when learning new concepts

- Can work abstractly for most previously-learned concepts

6th Grade and Beyond (ages 11+):

- Fluent at all three levels

- Choose the appropriate level for the problem complexity

- Still use concrete materials for advanced new concepts

But here’s what matters more than age: How solid is the understanding?

I’ve worked with twelve-year-olds who needed to return to concrete materials for fractions because they’d been pushed to algorithms too early. And I’ve seen seven-year-olds who moved fluidly between concrete and abstract because they’d been allowed to build genuine understanding.

Your child’s readiness is more important than her age.

What This Looks Like in Practice: A Real Example

Let me show you how this progression works with a specific concept: fraction equivalence.

Concrete Phase (might last weeks or months):

Your daughter uses Spielgaben’s pattern blocks (or any fraction manipulatives, or folded paper circles) to explore fractions physically. She discovers:

- 2 red trapezoids = 1 yellow hexagon (2/6 = 1/3)

- 3 blue rhombuses = 1 yellow hexagon (3/9 = 1/3)

- 6 green triangles = 1 yellow hexagon (6/18 = 1/3)

She’s building, comparing, discovering patterns. She’s not rushing. She’s understanding that fractions are relationships, not just numbers.

Representational Phase (might last weeks or months):

She starts drawing the shapes instead of building them. Her drawings get simpler—eventually just circles divided into parts, with sections shaded. She can show you 2/6 = 1/3 by drawing.

Abstract Phase (might last forever because it keeps expanding):

She can look at 2/6 and 1/3 and say “those are equivalent” without drawing or building. She can explain why. She can extend the pattern to find other equivalent fractions.

But here’s what’s crucial: When you introduce adding fractions with unlike denominators (a new, harder concept), she goes back to concrete materials.

This isn’t regression. This is exactly how mathematical understanding develops.

What About Using Manipulatives for “Too Long”?

Here’s the question parents ask me constantly: “Won’t my child become dependent on manipulatives if I let her use them too much?”

No. This is backwards thinking.

Dependency comes from premature abstraction, not from too much concrete experience. Here’s why:

A child who’s forced to work abstractly before she’s ready actually becomes dependent on:

- Memorizing procedures she doesn’t understand

- Anxiety-management strategies instead of mathematical thinking

- Constant reassurance that she’s doing it right

- You, sitting next to her, walking her through every problem

A child who works concretely until she’s genuinely ready to abstract becomes:

- Confident in her mathematical reasoning

- Able to self-correct errors

- Capable of tackling new problems independently

- Excited about math instead of afraid of it

The supposed “dependency” on manipulatives is actually mathematical confidence. She knows she has tools to figure things out.

Special Cases: When to Push a Little (Gently)

There are a few situations where you might encourage transition even if your child isn’t naturally moving there:

She’s avoiding challenge. If she reaches for blocks for 2+2 when she clearly understands this concept and could work abstractly, she might be using concrete materials as a security blanket rather than a learning tool.

What to do: “I notice you can solve these problems really quickly now without the blocks. Want to try the next few without them and see if they’re just as easy?”

She’s capable but hasn’t realized it yet. Sometimes children don’t notice their own readiness because they’re in the habit of using materials.

What to do: “Before you get the blocks out, let’s try something. Close your eyes and picture it. Can you see the answer? Okay, now check with the blocks and see if you were right.”

She’s working with numbers too large for concrete materials. Building 347+289 with individual blocks is tedious and counterproductive.

What to do: Transition to representational (base-ten blocks or place value drawings) or abstract work, but keep concrete materials available for checking understanding when she’s confused.

The Spielgaben Advantage (And Free Alternatives)

If you’re using Spielgaben, you already have materials specifically designed to support this concrete-to-abstract progression.

The gifts transition naturally through the three levels:

- Gifts 3-6 (solid blocks) are maximally concrete

- Gifts 7-8 (flat tiles and sticks) are representational—they’re two-dimensional drawings of three-dimensional concepts

- Gift 9 (points and lines) moves toward abstraction while maintaining visual representation

This progression is built into the materials, which reduces your planning burden. You’re not shopping for new materials as your child matures—you’re moving through a system designed for this developmental sequence.

But you absolutely don’t need Spielgaben to honor this progression.

Alternative approaches:

For concrete work:

- Any identical small objects (buttons, beans, LEGO, coins)

- Base-ten blocks

- Fraction circles or pattern blocks

- Counting bears or linking cubes

For representational work:

- Drawing on paper (free, always available)

- Graph paper for arrays and grids

- Ten-frames printed from the internet

- Number lines drawn or printed

For abstract work:

- Mental math

- Traditional written work

- Math apps that don’t use manipulative representations

The key isn’t what materials you use—it’s that you allow your child to work at the level she needs for each concept.

Your Action Plan for This Week

Don’t overcomplicate this. Here’s what to do:

1. Observe where your child naturally works this week.

For each concept or problem, notice:

- Does she reach for concrete materials?

- Does she draw pictures?

- Does she work abstractly?

- Does she get stuck and need to drop back to a previous level?

Just observe without judgment. You’re gathering data about where she is.

2. Make materials easily accessible.

If your child has to ask permission or wait for you to get materials out, she won’t use them when she needs them.

Set up a small basket or shelf with:

- Small manipulatives (buttons, beans, small blocks)

- Paper and pencils

- Whatever specific materials you’re using

3. Remove the pressure to “graduate.”

If someone comments that your child is “still using” manipulatives, you can smile and say: “She’s building genuine mathematical understanding, not just memorizing procedures. Research shows this creates much stronger math skills long-term.”

You don’t owe anyone an explanation beyond that.

4. Add one check-in question to your routine.

After your child solves a problem, occasionally ask: “Can you explain how you figured that out?”

If she can explain clearly at her current level (concrete, representational, or abstract), she’s working at the right level. If she can’t explain her thinking, she might need to drop back to more concrete work.

5. Trust the process.

Your child will naturally transition to more abstract thinking as she’s ready. Your job isn’t to push—it’s to provide the materials and space for understanding to develop at her pace.

The Long Game

Here’s what I want you to remember when you feel pressured to “move on” from manipulatives:

The goal isn’t to get your child to work abstractly as quickly as possible. The goal is to develop genuine mathematical understanding that will support increasingly complex thinking for the rest of her life.

A child who spends three months exploring fraction equivalence with pattern blocks will understand rational number relationships for the rest of her life.

A child who memorizes “cross-multiply to compare fractions” in two days will forget the procedure by next year and have no conceptual foundation for algebra.

Speed now costs understanding later.

Patience now creates mathematical power later.

Give your child the gift of time at the concrete level. You’re not slowing her down—you’re building the foundation that will allow her to soar when abstract concepts arrive.

She’ll get to abstract thinking. And when she does, it will be built on genuine understanding rather than memorized procedures.

That’s worth waiting for.

LEAVE A COMMENT