Who Was Friedrich Fröbel? The Man Who Discovered the True Child

When your child builds towers with wooden blocks or arranges colorful shapes into patterns, you’re watching something Friedrich Fröbel spent his lifetime understanding: play as the most serious work of childhood.

But before Fröbel became the father of kindergarten, he was a lonely boy locked behind high walls, finding friendship in the only place he could—among the flowers and trees of his father’s garden.

A Childhood Behind Walls

Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel was born in 1782 in the German village of Oberweißbach. His mother died when he was just ten months old. His father, a busy pastor, remarried, but his stepmother’s affection vanished once she had her own biological son.

Little Friedrich found himself isolated in the vicarage courtyard, essentially locked away from other children. But in that walled garden, something remarkable happened.

He began helping his father tend the plants. He watched seeds grow into flowers. He listened to what he later called the “language of the flowers” and experienced nature as the “garden of God.”

This lonely boy, abandoned by adults, became friends with creation itself.

The Gift of a Second Chance

Everything changed in 1792 when Friedrich’s uncle, Superintendent Hoffmann, recognized the boy’s unhappy situation. He took ten-year-old Friedrich to live with him in Stadtilm.

Fröbel later described this as his “second childhood”—a fresh start defined by kindness, trust, and freedom. For the first time, he played with other boys. He experienced what childhood could be when given room to grow.

This contrast shaped everything he would later teach. He saw firsthand the difference between constraint and freedom, between blocking a child’s development and nurturing it like a careful gardener.

Your homeschool gives your children what Friedrich’s uncle gave him: the freedom to grow in an environment of trust.

From Lost Boy to “Discoverer of the True Child”

Fröbel didn’t set out to become an educator. He trained as a forester, studied architecture, and wandered through various professions before finding his calling.

After working with the famous educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Fröbel opened his own school in Keilhau. But his most revolutionary insight came from watching children do what adults often dismissed as trivial: play.

What Fröbel Saw That Others Missed

Before Fröbel, play was considered “mere playfulness”—something children did when they weren’t doing real work. Fröbel completely flipped this understanding:

Play is the highest phase of child development. It’s how children freely express their inner being and make sense of the world around them.

Play is serious work. He observed that a child who plays “self-actively, quietly, and perseveringly” will grow into an adult capable of persistence and self-sacrifice.

Play makes the inner external. Through manipulating objects and creating patterns, children internalize outer reality and express their inner thoughts.

The educator Martha Muchow later called Fröbel the “discoverer of the real child” because he saw what had always been hidden in plain sight: children’s play is their natural curriculum.

The Moment “Kindergarten” Was Born

In 1840, while hiking through the Thuringian mountains, Fröbel experienced what he described as a revelation. The word came to him: Kindergarten—literally, “children’s garden.”

He rejected the word “school” for young children because it felt too rigid, too institutional. He wanted a “play garden” where children could be cultivated like noble plants, growing in harmony with nature and their own divine spark.

The metaphor went deeper than the name. Just as his childhood garden had been his sanctuary and teacher, he envisioned educational spaces where children could grow naturally, with gentle guidance rather than forced instruction.

Why Fröbel Still Matters in Your Homeschool

You might wonder what a 19th-century German educator has to do with your kitchen table or living room floor in 2025.

Everything.

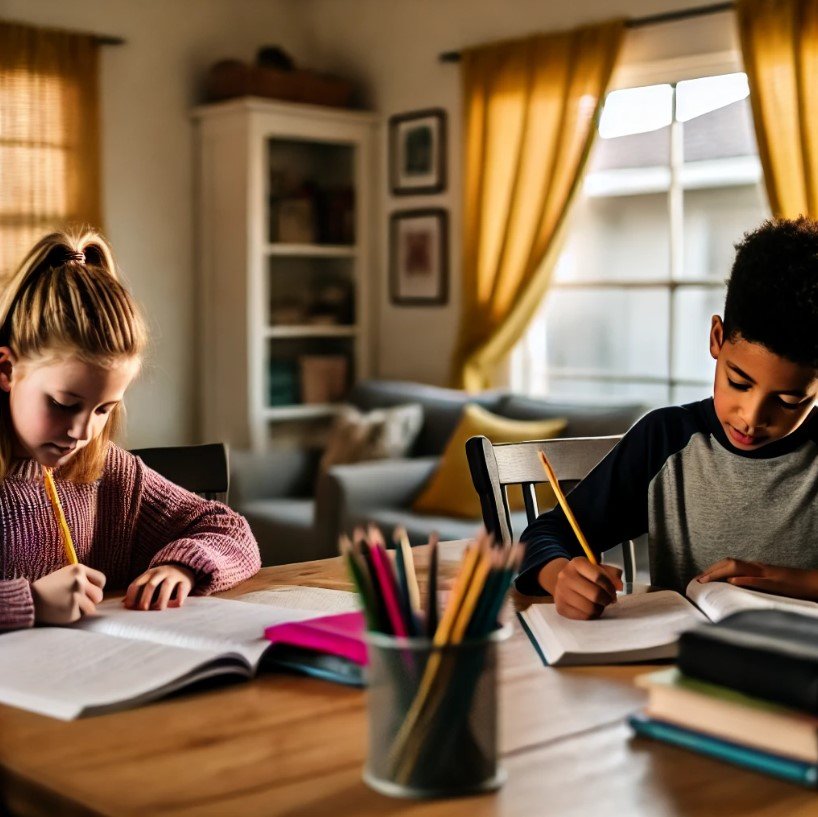

When you set out manipulatives and step back to watch what your child creates, you’re practicing Fröbel’s core insight. You’re trusting that play is not something that happens before real learning begins—play IS real learning.

When you take nature walks and let your children collect treasures, you’re echoing Fröbel’s garden childhood. He believed nature was humanity’s first and most essential teacher.

When you resist the urge to constantly correct and direct, choosing instead to cultivate what’s already within your child, you’re acting as a Fröbelian gardener. You’re not manufacturing a product; you’re nurturing a seed that already contains everything it needs.

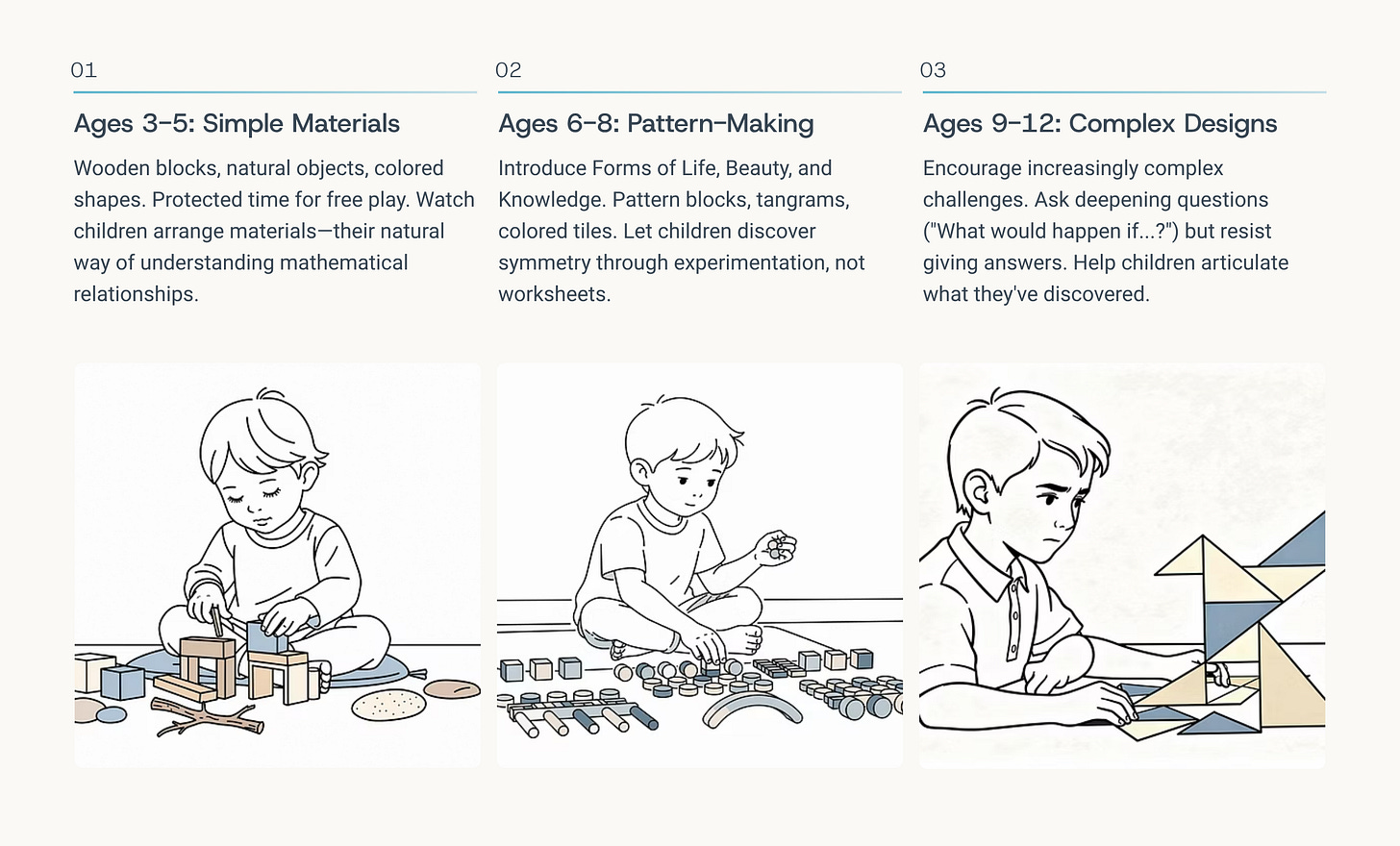

How This Translates to Your Day

For ages 3-5: Provide simple materials—wooden blocks, natural objects, colored shapes—and protected time for free play. Fröbel would spend an entire morning watching children arrange and rearrange materials, recognizing this as their natural way of understanding mathematical and spatial relationships.

For ages 6-8: Introduce pattern-making activities using manipulatives like Spielgaben’s Forms of Life, Forms of Beauty, and Forms of Knowledge (or substitute: pattern blocks, tangrams, colored tiles). Let children discover symmetry, balance, and mathematical concepts through their own experimentation rather than through worksheets.

For ages 9-12: Encourage increasingly complex designs and challenges. Ask questions that deepen their thinking (”What would happen if…?” “Can you create the opposite?”) but resist giving answers. Fröbel called this “making the inner external”—helping children articulate what they’ve discovered through their hands.

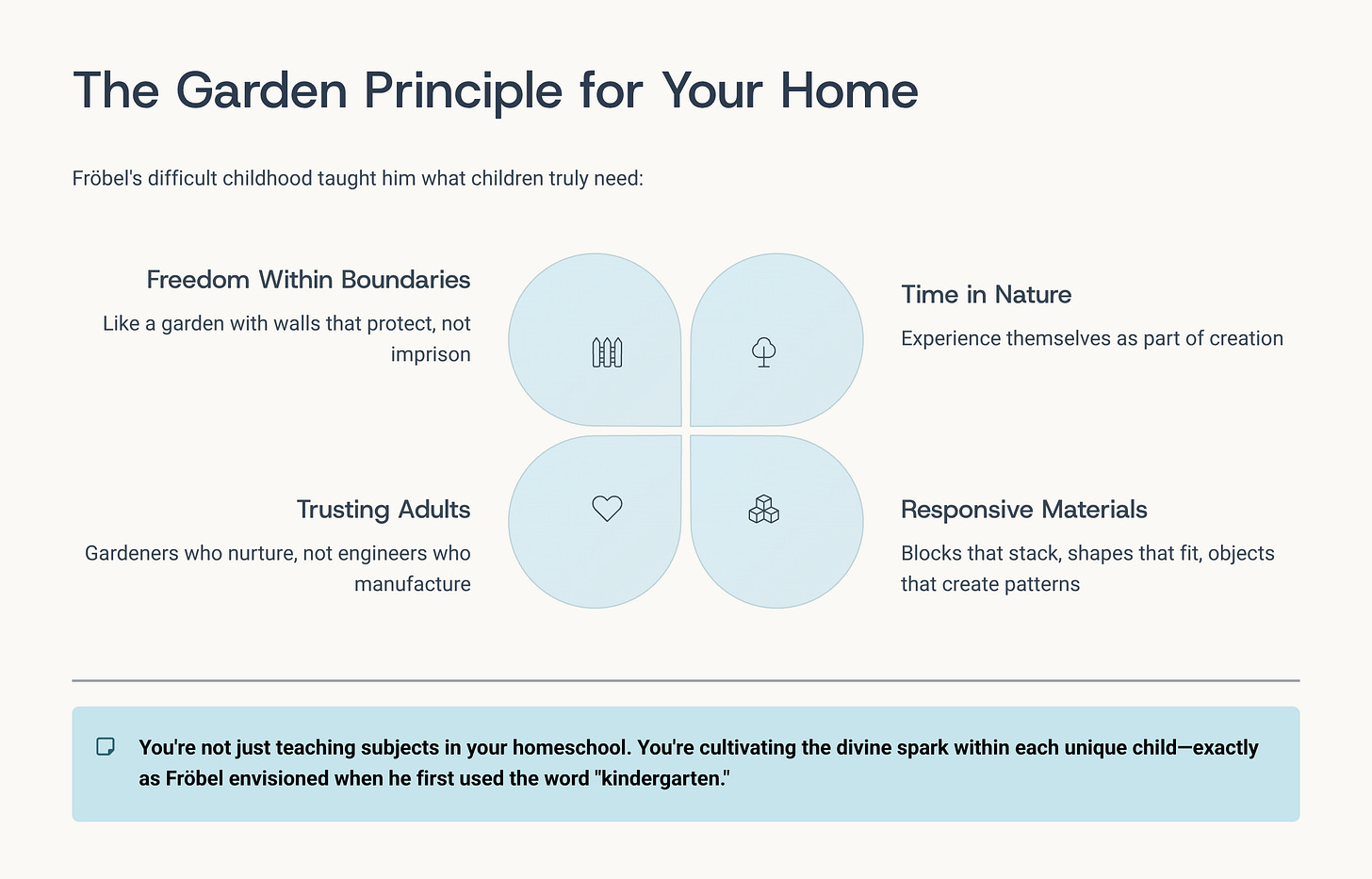

The Garden Principle for Your Home

Fröbel’s life embodied what he called “Life Unity”—bringing God, nature, and humanity into harmony. His difficult childhood taught him that children need:

- Freedom within boundaries (like a garden with walls that protect rather than imprison)

- Time in nature (where they experience themselves as part of creation)

- Materials that respond to their touch (blocks that stack, shapes that fit, objects that create patterns)

- Adults who trust their process (gardeners who nurture, not engineers who manufacture)

You’re not just teaching subjects in your homeschool. You’re cultivating the divine spark within each unique child—exactly as Fröbel envisioned when he first used the word “kindergarten.”

Coming Next: In our next article, we’ll explore Fröbel’s philosophy of “Holistic Learning”—how he sought to educate the Head, Heart, and Hand together, and what that means for your homeschool curriculum choices today.

Have you noticed your children learning through play in ways that surprised you? I’d love to hear your observations. Reply or comment and share your story.

LEAVE A COMMENT