The “Discoverer of the True Child”: Why Play is More Than Just Fun

Last week, we met Friedrich Fröbel—the lonely boy in a walled garden who grew up to revolutionize how we understand childhood. Today, we’re diving into his most important insight, the one that earned him the title “discoverer of the real child.”

Here it is: Play isn’t what children do when they’re not learning. Play is how children learn everything that matters.

This wasn’t obvious in Fröbel’s time. It still isn’t obvious to many adults today.

What Everyone Else Saw

Before Fröbel, educated adults across Europe believed children’s play was “mere playfulness”—a way to burn energy until they were mature enough for real instruction.

Play was the appetizer. School was the main course.

Parents tolerated play. Teachers waited for it to end. And children? They were rushed through childhood as quickly as possible toward “serious” adult work.

Fröbel watched children differently.

What Fröbel Saw

He observed something radical: “Playing and being a child are the same thing.”

Not similar. Not related. The same thing.

A child who no longer wants to play, Fröbel believed, is actually sick—they’ve lost their natural drive for development. This wasn’t metaphor. He meant it clinically. A child’s desire to play is as essential as their desire to eat or sleep.

Why? Because play is the highest phase of development in childhood. It’s the free expression of a child’s inner being.

The Bridge Between Inner and Outer Worlds

Here’s where Fröbel’s thinking gets profound.

Through play, children do something miraculous: they make their “inner external and outer internal.”

Let me translate that into kitchen-table language:

Making the inner external: Your child has thoughts, feelings, ideas, and understanding that exist only in their mind and heart. Through play—building towers, arranging patterns, creating worlds—they make those invisible inner realities visible and tangible.

Making the outer internal: The world is big and complex and overwhelming. Through play, your child takes that external chaos, shrinks it down to manageable size, recreates it with blocks or dolls or drawings, and makes it understandable. They internalize reality by recreating it.

Play is the bridge. It’s how the soul speaks to the world and how the world speaks to the soul.

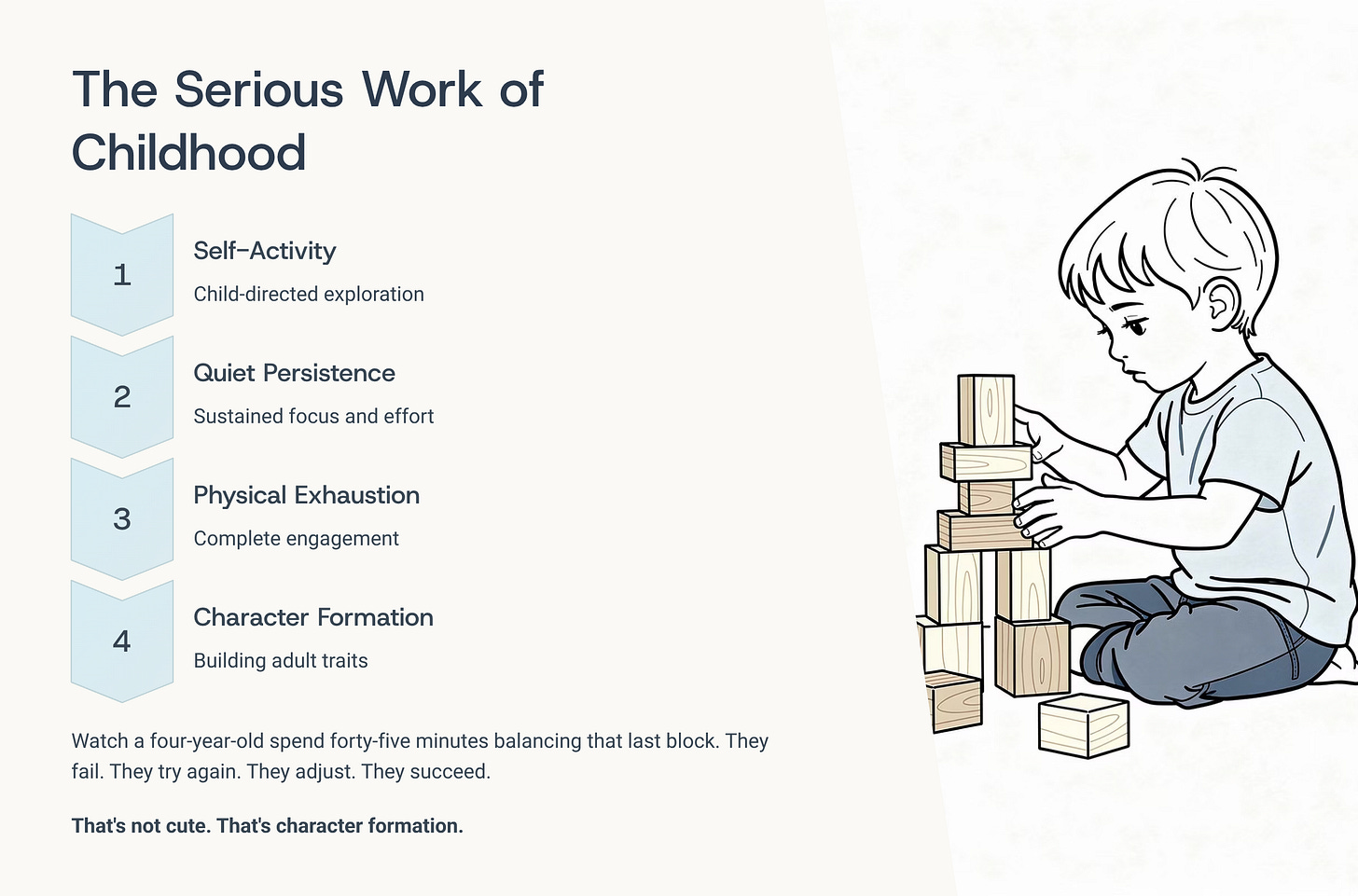

The Serious Work of Childhood

You’ve probably said it yourself: “They’re just playing.”

Fröbel would gently push back on that “just.”

He observed that when a child plays “self-actively, quietly, and perseveringly” until physically exhausted, something remarkable is happening. That child isn’t merely having fun. They’re building the character traits that will define them as adults: perseverance, focus, the capacity for sustained effort, even self-sacrifice.

Watch a four-year-old spend forty-five minutes trying to balance that last block on top of a tower. They fail. They try again. They adjust their approach. They slow down. They succeed.

That’s not cute. That’s character formation.

The play has “great seriousness and deep meaning,” even though it looks simple from the outside. Especially when it looks simple from the outside.

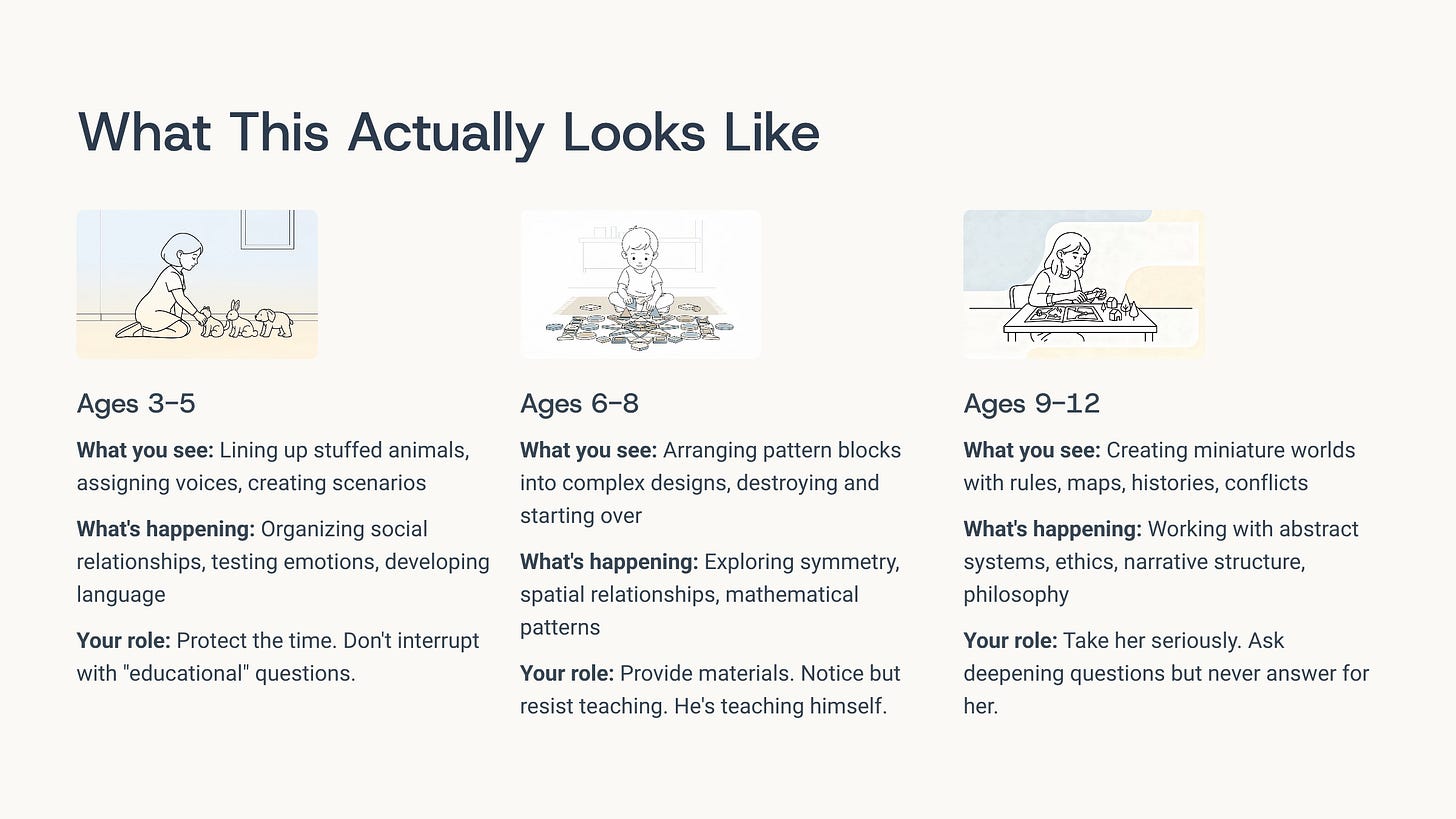

What This Actually Looks Like

Ages 3-5:

- What you see: Your daughter lines up her stuffed animals, assigns them names, gives them different voices, creates elaborate scenarios

- What’s actually happening: She’s organizing social relationships, testing emotional responses, working through her own experiences, developing language and narrative thinking

- Your role: Protect the time and space. Don’t interrupt with “educational” questions. The education is already happening.

Ages 6-8:

- What you see: Your son arranges pattern blocks (or Spielgaben shapes, colored tiles, tangrams—whatever you have) into increasingly complex designs, then destroys them and starts over

- What’s actually happening: He’s exploring symmetry, balance, spatial relationships, color theory, mathematical patterns—all without a single worksheet

- Your role: Provide materials that respond to his manipulation. Wooden blocks are better than plastic because they stack less easily—the resistance teaches. Notice what he’s working on, but resist the urge to teach. He’s already teaching himself.

Ages 9-12:

- What you see: Your daughter creates an entire miniature world with specific rules, maps, histories, conflicts, and resolutions

- What’s actually happening: She’s working with abstract systems, cause and effect, governance, ethics, narrative structure, worldbuilding—the foundations of philosophy, political science, and creative thinking

- Your role: Take her seriously. Ask questions that deepen her thinking (”What would happen if…?” “How did you decide…?”) but never answer for her. She’s not playing at something. She’s genuinely creating.

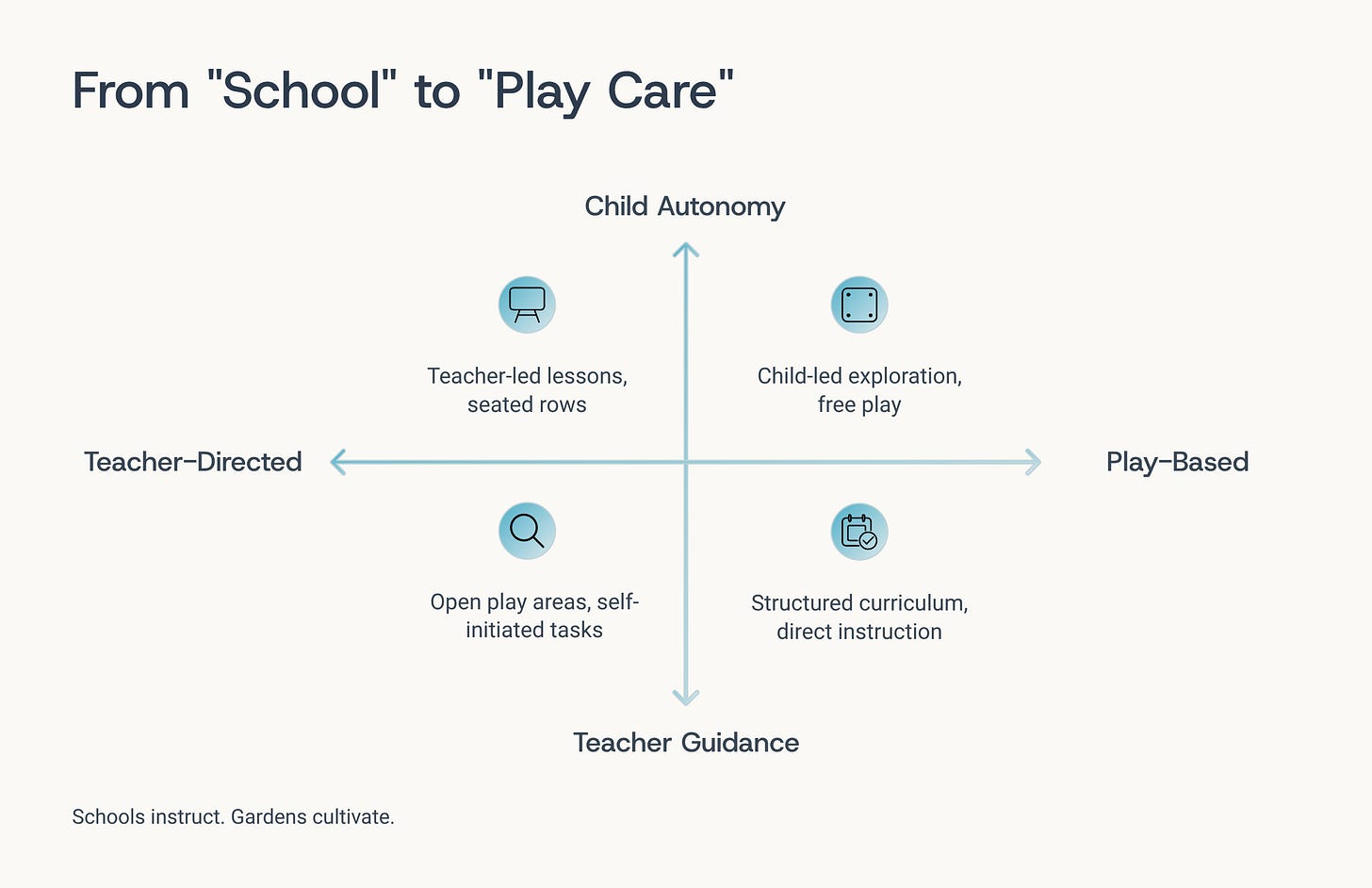

From “School” to “Play Care”

Because Fröbel recognized play as the child’s primary “developmental medium,” he rejected traditional instruction for young children entirely.

This is why he called it “kindergarten” (children’s garden) instead of “school.”

Schools instruct. Gardens cultivate.

He believed the educator’s task wasn’t to fill children with facts through “frontal verbal instruction”—standing at the front of the room, talking at seated children.

Instead, educators should provide “play care”: supporting children’s self-activity by giving them space, time, and materials to develop their own inner strengths.

What Play Care Means in Your Home

It means you’re not the instructor. You’re the gardener.

Gardeners don’t make plants grow. They create conditions for growth:

- Rich soil (materials that respond to manipulation)

- Sunlight (protected time without interruption)

- Water (gentle guidance when requested)

- Space (freedom to grow in their own direction)

Practical play care looks like:

The materials you provide:

- Natural materials (wood, stones, shells, pinecones)

- Simple geometric shapes (blocks, Spielgaben, or homemade alternatives from cardboard)

- Open-ended items that can become anything (fabric scraps, boxes, sticks)

- Tools that require skill development (child-safe scissors, pencils, paintbrushes)

The time you protect:

- Minimum 1-2 hours of uninterrupted play daily for ages 3-8

- No screen interruptions during play time

- No rushing to “activities” or structured lessons during peak play hours (usually mid-morning)

- Long stretches (even weeks) with the same materials, allowing deep exploration

The space you create:

- A dedicated play area where half-finished creations can stay out

- Low shelves where children can access materials independently

- Natural light and, ideally, access to outdoor space

- Simplicity over abundance—too many toys paralyzes choice

The restraint you practice:

- Watching without commenting

- Allowing failure and repetition

- Not asking “What is it?” when they create something

- Resisting the urge to show them the “right” way

This is harder than it sounds. We’re trained to instruct. Fröbel asks us to trust instead.

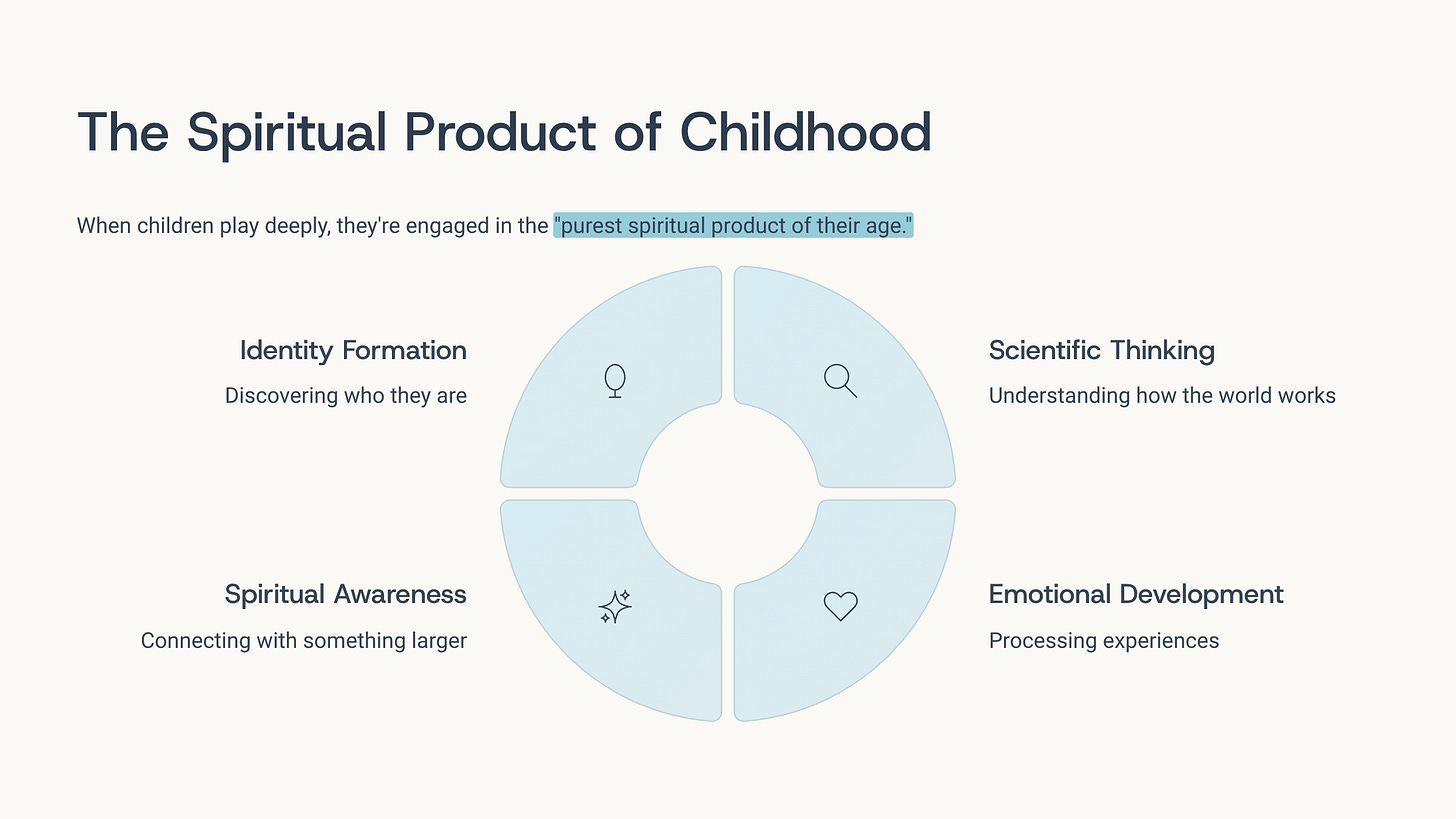

The Spiritual Product of Childhood

Fröbel used religious language that might sound old-fashioned, but his point remains urgent: when children play deeply, they’re engaged in what he called “the purest spiritual product of their age.”

Spiritual here doesn’t necessarily mean religious (though it can). It means essential to the soul.

Play is how children:

- Discover who they are (identity formation)

- Understand how the world works (scientific thinking)

- Process what they’ve experienced (emotional development)

- Connect with something larger than themselves (spiritual awareness)

When we respect play as a serious necessity rather than optional entertainment, we protect what Fröbel called the “divine spark” in our children. We help them find “Life Unity”—a harmony between themselves, nature, and their Creator (however you understand that term).

What Changes When You See Play Differently

Before Fröbel’s insight: “Stop playing and come do your schoolwork.”

After Fröbel’s insight: “Your play time is your schoolwork. Everything else supports it.”

Before: Worksheets at 8am, play as a reward at 2pm if work is finished.

After: Protected play time during peak mental hours, with any formal instruction happening during naturally lower-energy times.

Before: “What are you making? Is that a house? Let me show you how to make it better.”

After: Silent observation, genuine curiosity, trust that they know what they’re building even if you don’t recognize it yet.

Starting Tomorrow

If this philosophy resonates but feels overwhelming to implement, start with just one change:

Protect two hours of play time tomorrow morning. That’s it.

No lessons. No worksheets. No “educational games.” Just materials (blocks, shapes, natural objects, whatever you have) and time.

Watch what happens when you stop interrupting their natural developmental process.

Most parents report being stunned by what emerges when children are given sustained time with simple materials. The complexity, the focus, the problem-solving, the creativity—it was always there. We just kept interrupting it.

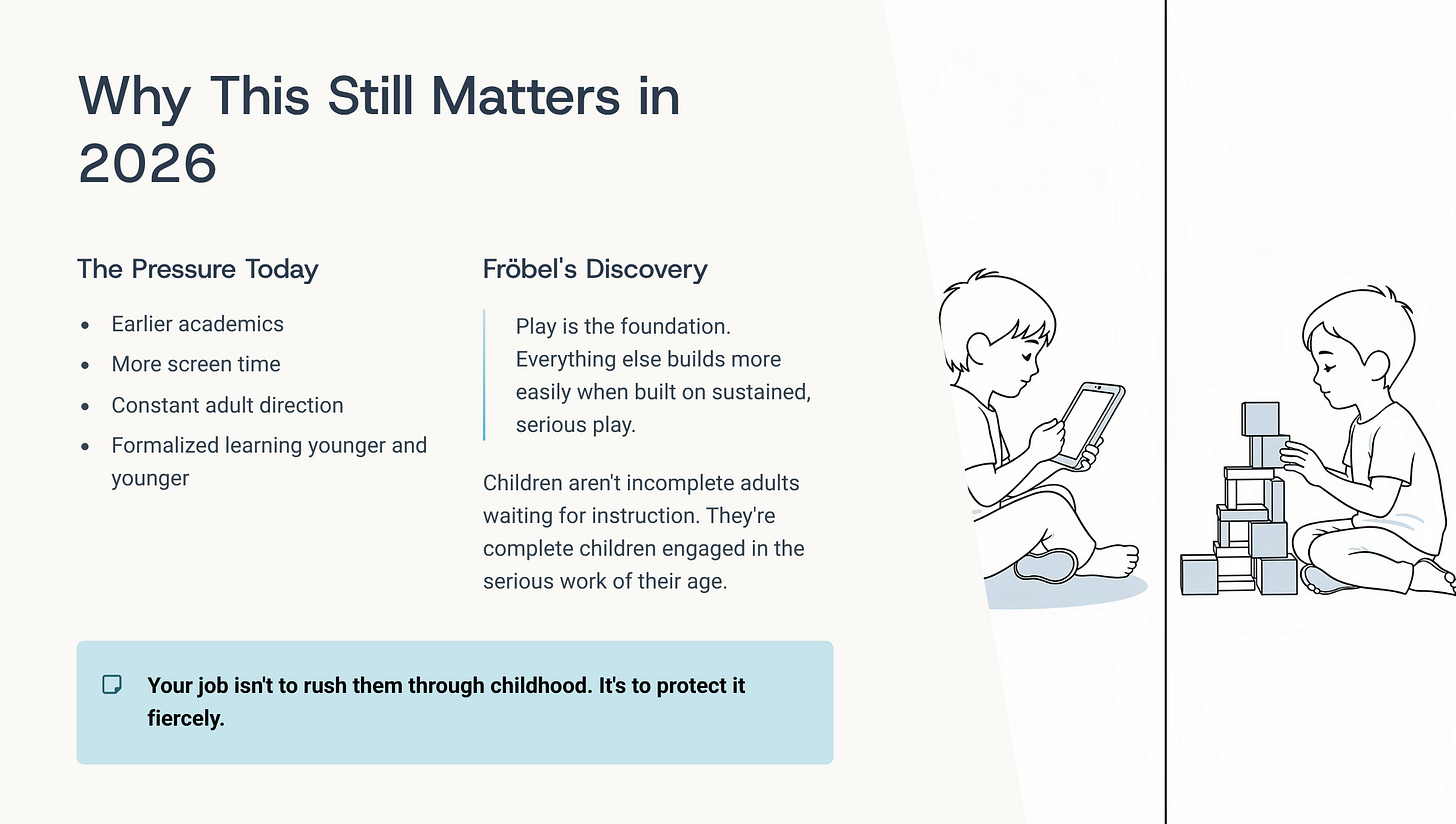

Why This Still Matters in 2026

We live in an age of earlier academics, more screen time, and constant adult direction. The pressure to formalize learning younger and younger grows every year.

Fröbel’s discovery stands against all of it.

Not because formal academics are inherently bad, but because trying to build a house before the foundation is set guarantees structural problems later.

Play is the foundation. Everything else—reading, writing, mathematics, science, history, art—builds more easily and more solidly when built on the foundation of self-directed, sustained, serious play.

Martha Muchow called Fröbel “the discoverer of the real child” because he saw what everyone else had missed: children aren’t incomplete adults waiting for instruction. They’re complete children engaged in the serious work of their age.

Your job isn’t to rush them through childhood. It’s to protect it fiercely.

Coming Next: We’ve explored who Fröbel was and why play matters. Next, we’ll examine the how—his philosophy of “Holistic Learning” and what it means to educate the Head, Heart, and Hand together in your homeschool.

Has understanding play as serious work changed anything about your homeschool day? I’d love to hear what you’re discovering. Reply and share your observations.

P.S. If you’re looking for simple materials to support serious play, the Spielgaben sets were designed specifically around Fröbel’s principles—but honestly, a set of plain wooden blocks, some natural materials from your backyard, and protected time will accomplish the same thing. The materials matter less than your understanding of what’s happening when you step back and let children work.

LEAVE A COMMENT