The Birth of the Kindergarten: When “Babysitting” Became Education

We’ve explored who Friedrich Fröbel was and why he believed play is serious work. Today, we’re looking at what he actually built with those insights—and why it sparked both a revolution and a government ban.

The question Fröbel answered: What’s the difference between keeping children safe and actually educating them?

His answer changed early childhood care across the globe.

What Already Existed in 1839

Long before Fröbel founded his kindergarten, working parents needed somewhere to put their children during the day.

Enter the Kinderbewahranstalten—literally “child safeguard institutions” or “infant schools.”

These weren’t cruel places. They served a real economic need, especially during harvest seasons when both parents worked long hours in the fields. Children were gathered together, kept safe, given basic care, and “unattended” in the sense that they weren’t actively taught anything in particular.

The goal was simple: prevent harm until parents returned.

Children were safeguarded the way you might safeguard valuables in a vault—protected from damage, but not expected to grow or develop. Staff watched them. Fed them. Broke up fights. Sent them home intact.

That was considered enough.

What Fröbel Saw That Others Didn’t

Fröbel looked at these institutions and recognized they were missing something essential: a systematic pedagogical program rooted in the nature of childhood itself.

“Safeguarding” treated children as passive objects to be preserved.

“Educating” recognizes children as active beings in the midst of their most critical developmental phase.

The difference isn’t semantic. It’s fundamental.

Safeguarding asks: “How do we keep children from being harmed until they’re old enough for real education?”

Educating asks: “What does this specific phase of human development require, and how do we provide it?”

Fröbel’s decisive step was creating places dedicated not just to keeping children safe, but to the education, training, and care of the whole child.

The Moment “Kindergarten” Was Born

In 1839, Fröbel founded an institution in Blankenburg. He called it the “Institution for the Cultivation of the Activity Instinct.”

Accurate? Yes. Memorable? Not remotely.

Then, in 1840, during a hike from Blankenburg to Keilhau, the right word came to him. He later described it as a “revelation.”

Kindergarten. Children’s garden.

Why “Garden” Instead of “School”?

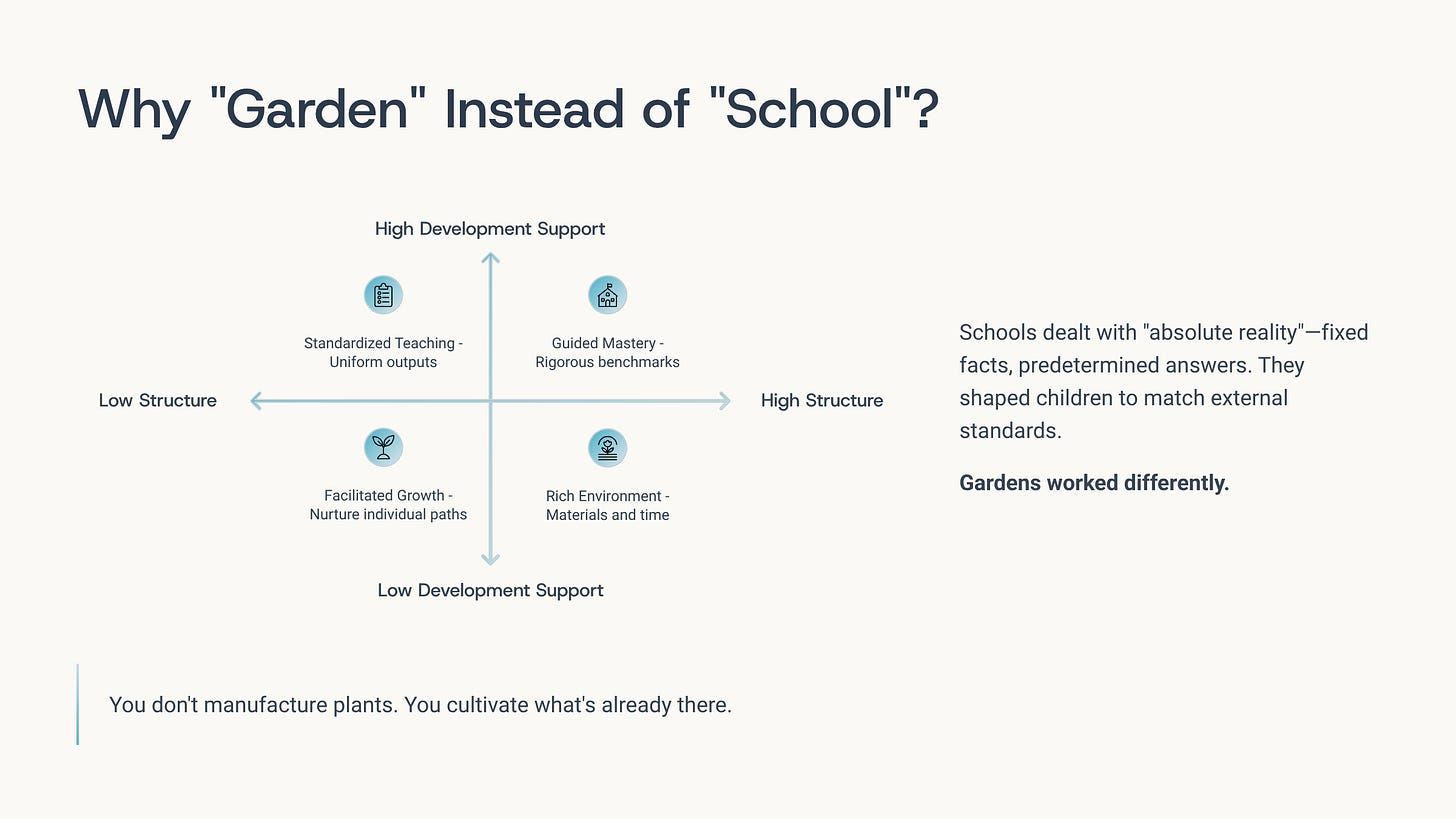

This wasn’t poetic license. Fröbel deliberately rejected the word “school” for young children.

Schools, in his view, dealt with “absolute reality”—fixed facts, predetermined answers, knowledge transferred from teacher to student. Schools shaped children to match external standards.

Gardens worked differently.

In a garden, you don’t manufacture plants. You cultivate what’s already there.

Each seed contains its own potential. The gardener’s job is to provide:

- Rich soil (appropriate materials)

- Sunlight (protected time and space)

- Water (gentle guidance)

- Protection from harsh weather (safety without confinement)

- Patience (trust in natural developmental timing)

Fröbel viewed children as “noble plants” and small seeds that should be cultivated in harmony with nature, humanity, and God. The educator’s role wasn’t to fill children with predetermined content but to provide “play care”—nurturing the “divine spark” already within each child toward its full expression.

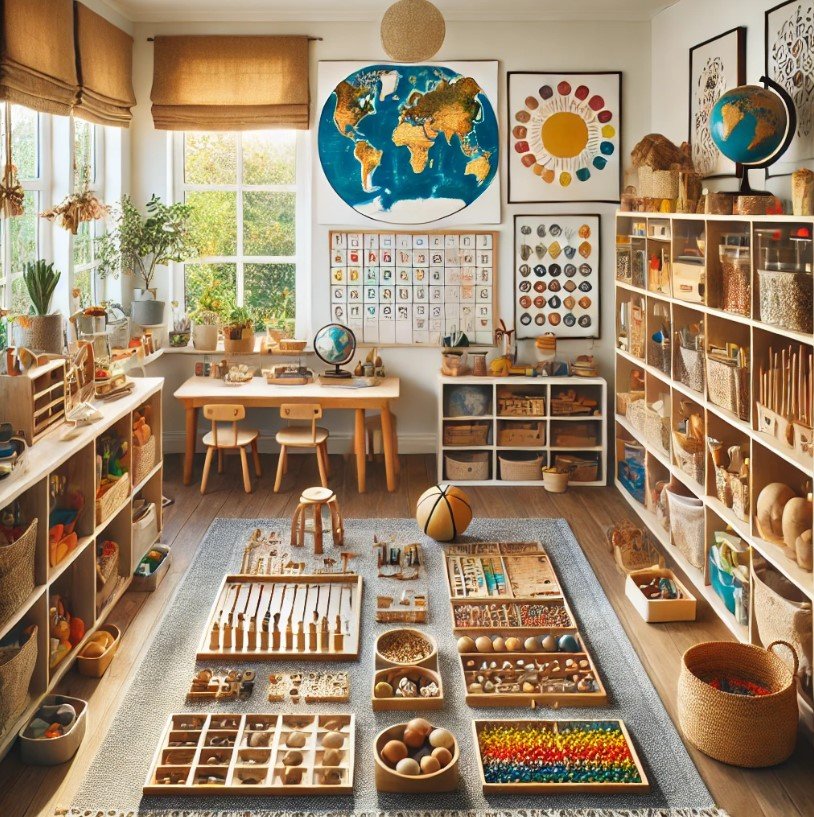

The metaphor went all the way down. Even the layout of early kindergartens included actual gardens where children could observe growth, tend plants, and participate in the cycles of nature.

A New System: The Triad of Care

The Fröbelian kindergarten introduced something genuinely revolutionary: a unified system defined by education, upbringing, and care working together—not as separate functions, but as three aspects of the same thing.

Traditional schools educated (filling minds with information). Orphanages provided care (meeting physical needs). Families handled upbringing (shaping character and values).

Fröbel’s kindergarten did all three simultaneously, through a single medium: play.

The Three Pillars

1. Play as the Primary Medium

Remember Fröbel’s insight: “Playing and being a child are the same thing.”

This wasn’t a teaching method. It was recognition of reality. You can’t separate a young child from play any more than you can separate a plant from photosynthesis. It’s the fundamental process through which development happens.

Therefore, all education for young children should happen through play and self-activity—not as a reward for completing “real work,” but as the real work itself.

2. The Educator as “Play Leader”

Teachers in Fröbel’s kindergarten weren’t called “instructors.” They were Spielführerinnen—play leaders or play companions.

Their job wasn’t to:

- Stand at the front delivering information

- Correct children toward predetermined outcomes

- Fill empty vessels with knowledge

- Train children in specific skills

Their job was to:

- Observe what naturally emerged in children’s play

- Provide materials that supported emerging interests

- Follow the child’s natural instincts while gently guiding

- Remove obstacles to development

- Protect sustained play from unnecessary interruption

The play leader doesn’t lead the parade. They clear the path.

3. Holistic Development

Fröbel’s system focused on the “whole” human being—biological, psychological, and social development happening simultaneously.

This meant:

- Physical development through movement and manipulation of objects

- Cognitive development through pattern-making and problem-solving

- Social development through shared play and cooperation

- Emotional development through creative expression

- Spiritual development through connection with nature and beauty

Early childhood wasn’t “preparation” for later life. It was an irretrievable and essential phase with its own dignity and purpose.

Children weren’t incomplete adults. They were complete children.

What This Actually Looked Like (Then and Now)

Let me translate Fröbel’s 1840 kindergarten into terms that help you see what he was doing—and how it applies to your homeschool.

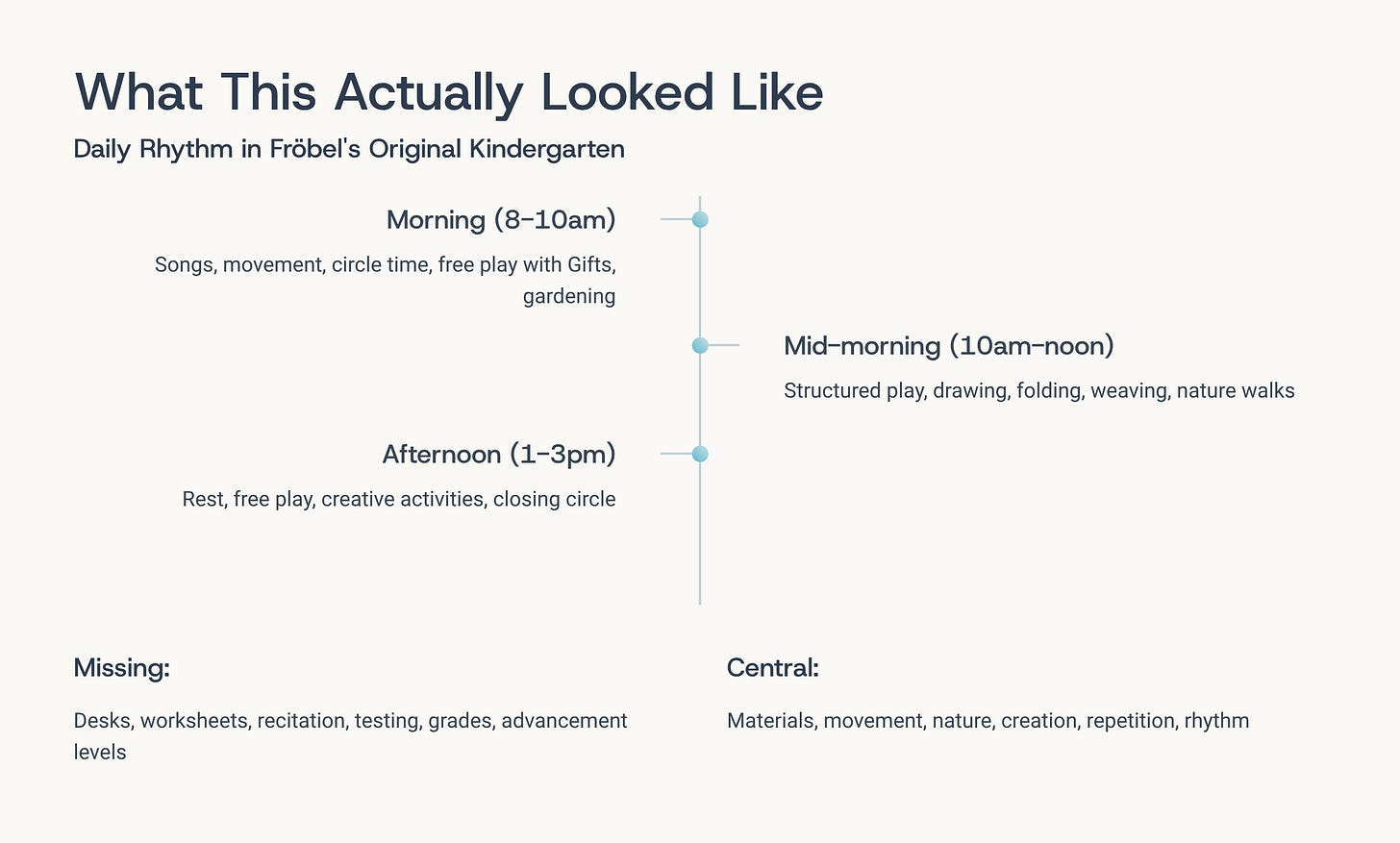

Daily Rhythm in Fröbel’s Original Kindergarten

Morning (roughly 8-10am):

- Arrival with songs and movement

- Circle time with stories, finger plays, simple games

- Free play with the Gifts (wooden blocks, balls, shapes)

- Gardening time in actual outdoor gardens

Mid-morning (roughly 10am-noon):

- Structured play with materials

- Drawing, paper folding, weaving (the Occupations)

- Songs and movement games

- Nature walks and observation

Afternoon (roughly 1-3pm):

- Rest or quiet activities

- More free play

- Creative activities

- Closing circle

Notice what’s missing: desks, worksheets, recitation, testing, grades, advancement levels.

Notice what’s central: materials, movement, nature, creation, repetition, rhythm.

How This Translates to Your Homeschool

You’re not running an institution. You’re a parent-educator working with your own children. But Fröbel’s three pillars still apply.

For Ages 3-5: The Foundation Years

Your role as play leader:

- Set out simple materials in the morning (blocks, shapes, natural objects, art supplies)

- Observe what captures their attention

- Resist the urge to direct or improve their creations

- Protect 2-3 hours of uninterrupted play time

- Introduce new materials gradually based on what they’re working on

What holistic development looks like:

- Physical: Building towers teaches hand-eye coordination, finger strength, spatial awareness

- Cognitive: Creating patterns develops mathematical thinking without numbers or symbols

- Social: Sharing materials teaches negotiation, turn-taking, cooperation

- Emotional: Free creation allows expression of inner states without words

- Spiritual: Connection with natural materials (wood, stones, water) creates awareness of the created world

Concrete example: Your 4-year-old spends an hour arranging colored wooden blocks by size, then by color, then by size within color groups. They’re not “just playing.” They’re working on classification systems—the foundation of logic, mathematics, and scientific thinking. Your job is to not interrupt this with “helpful” suggestions or questions like “What are you making?”

For Ages 6-8: Expanding the Garden

Your role as play leader:

- Introduce more complex materials (Spielgaben Forms of Life/Beauty/Knowledge, tangrams, pattern blocks, weaving materials, simple tools)

- Ask questions that extend thinking without providing answers (”What would happen if…?” “How could you…?”)

- Invite them into real work alongside play (cooking, gardening, simple repairs)

- Allow sustained projects that take days or weeks

What holistic development looks like:

- Physical: Fine motor skills through drawing, cutting, weaving, folding

- Cognitive: Abstract thinking through pattern replication and creation

- Social: Collaborative projects with siblings or friends

- Emotional: Expression through art, storytelling, dramatic play

- Spiritual: Observing cycles and patterns in nature, creating beauty

Concrete example: Your 7-year-old discovers they can create symmetrical designs with pattern blocks. For three weeks, they make increasingly complex symmetrical patterns each morning. They’re learning geometry, spatial relationships, mirror imaging, and the mathematical concept of symmetry—without a single worksheet. They’re also building focus, persistence, and aesthetic judgment.

For Ages 9-12: Sophisticated Play

Your role as play leader:

- Provide materials for increasingly sophisticated creation (advanced building sets, art supplies, tools, raw materials)

- Support long-term projects without taking them over

- Connect their interests to formal learning when they’re ready

- Respect that play looks different but remains essential

What holistic development looks like:

- Physical: Complex manipulation, tool use, extended projects requiring stamina

- Cognitive: Abstract problem-solving, system design, hypothesis testing

- Social: Leadership, collaboration, conflict resolution in group projects

- Emotional: Expression of complex ideas and feelings through creation

- Spiritual: Questions about meaning, purpose, beauty, contribution

Concrete example: Your 10-year-old becomes obsessed with bridge design. They spend weeks building increasingly complex bridges from blocks, then cardboard and tape, then branches and string. They test weight limits. They research real bridges. They redesign based on failure. This is physics, engineering, materials science, mathematics, and perseverance—all emerging from sustained play with materials. Eventually, they might be ready for a book about bridge engineering, but the foundation is already built.

The Spread and the Ban

On June 28, 1840, Fröbel officially established the first “General German Kindergarten” in Blankenburg.

It lasted exactly eleven years before the Prussian government banned it.

Why the Ban?

In 1851, the Prussian Ministry of Education declared kindergartens part of a “socialist system” that threatened traditional social structures. The government feared that Fröbel’s emphasis on the child’s inner nature and self-activity undermined authority and promoted dangerous individualism.

They weren’t entirely wrong about what kindergarten threatened.

If you genuinely believe each child contains a “divine spark” that should be nurtured according to its own nature rather than shaped to fit external requirements, you are promoting a fairly radical view of human development and social organization.

The Unexpected Consequence

The ban backfired spectacularly.

Fröbel’s trained teachers emigrated, taking the “kindergarten” idea across Europe, to America, to Japan, to Australia. The German word “kindergarten” became standard terminology for early childhood education in over 40 languages—one of the few German words to achieve truly global usage.

The ban that was meant to suppress the idea instead spread it worldwide.

By the early 20th century, kindergartens existed on every inhabited continent. Fröbel’s insight that early childhood required its own dedicated educational approach—not just safeguarding, not just preparation for “real school”—became foundational to modern early childhood education.

Even institutions that don’t follow Fröbel’s methods anymore still carry his central insight: this phase of life matters on its own terms.

What This Means for Your Homeschool

Fröbel’s transition from “keeping” to “educating” asks you a pointed question:

Are you safeguarding your children’s time, or are you cultivating their development?

Both have value. Safety matters. But Fröbel would push you to ask whether your daily rhythm creates a “play garden” where inner thoughts can be made external through materials and time, or just a safe holding pattern until “real learning” begins.

Practical Questions to Ask Yourself

About materials:

- Do you provide materials that respond to manipulation? (Blocks stack and fall; screens don’t.)

- Are materials simple enough that children must add their own creativity? (Generic blocks become anything; themed playsets become only one thing.)

- Can children access materials independently, or must they ask permission for everything?

About time:

- Do you protect sustained play time (minimum 1-2 hours for ages 3-8), or is play always fragmented into 15-20 minute windows?

- Does play happen during children’s peak mental energy (usually morning), or only as afternoon reward?

- Can children leave creations out overnight to continue the next day?

About your role:

- Do you observe more than you direct?

- Can you watch play without asking “What is it?” or offering improvements?

- Do you see yourself as a gardener providing conditions, or a manufacturer producing outcomes?

About philosophy:

- Do you view early childhood as preparation for “real learning,” or as essential education on its own terms?

- Is your goal to fill your children with predetermined knowledge, or to nurture what’s already within them?

- Are you safeguarding time, or cultivating development?

Moving from Safeguarding to Play Care

If you recognize you’ve been more focused on safeguarding (keeping children busy, preventing problems) than educating (creating conditions for development), here’s how to shift:

Week 1: Observe without changing anything

- Watch what your children do during free time

- Notice what materials they return to repeatedly

- Track how long they stay engaged before asking for intervention

- Document what you learn

Week 2: Simplify and consolidate

- Remove half the toys (yes, really—abundance paralyzes choice)

- Keep only open-ended materials (blocks, art supplies, natural objects, simple tools)

- Create accessible storage so children can set up independently

- Clear a space where half-finished projects can stay out

Week 3: Protect time

- Block out 2 hours of play time during peak energy (usually 9-11am)

- Remove your own agenda for this time

- Practice non-intervention unless safety is at risk

- Resist fixing, teaching, or improving their creations

Week 4: Notice what emerges

- What themes keep appearing in their play?

- What problems are they working on?

- What skills are developing without your instruction?

- How has the quality of engagement changed?

Most parents report being shocked by what emerges when they stop interrupting natural development. The focus, complexity, and learning were always there—we just kept disrupting them with our helpful involvement.

The Garden Principle

Fröbel didn’t call it kindergarten because it sounded nice. He called it a garden because that’s what it was: a protected space where living things grow according to their nature when given appropriate conditions.

You can’t make a seed grow faster by pulling on the shoot. You can’t make it grow straighter by tying it to a stick before it needs support. You can’t make it bloom earlier by painting the buds.

You can only provide: rich soil, sufficient light, appropriate water, protection from harsh conditions, and patient trust in the seed’s inherent program.

The same applies to children.

Your homeschool can be a kindergarten in Fröbel’s original sense: not a rigid institution, but a protected garden where the divine spark within each child is carefully, patiently, trustingly cultivated toward its full expression.

Not shaped to match external standards. Not rushed through natural phases. Not manufactured toward predetermined outcomes.

Cultivated. Like noble plants. Like small seeds containing everything they need to become what they’re meant to be.

That’s the difference between safeguarding and education.

That’s why kindergarten sparked a revolution.

That’s what your homeschool can be.

Coming Next: We’ve covered who Fröbel was, why play matters, and what kind of space supports development. Next, we dive into his philosophy of “Holistic Learning”—how to educate the Head, Heart, and Hand together, and what that looks like in practical daily rhythm.

Have you noticed the difference between safeguarding time and cultivating development in your own home? What shifted when you stopped interrupting natural play? Reply and share your observations—I learn as much from you as you learn from these articles.

P.S. The Spielgaben sets were designed as modern versions of Fröbel’s original Gifts—materials specifically created to support self-directed developmental play. But the principle works with whatever you have: plain wooden blocks, natural materials from outside, simple art supplies, basic tools. The materials matter far less than your understanding of what’s happening when you step back and trust the process.

LEAVE A COMMENT