Making the Inner External: The Heart of Fröbelian Learning

We’ve explored Froebel’s life, his discovery of play as serious work, and how kindergarten transformed from safeguarding to cultivation. Now we’re diving into the mechanism itself—the actual process through which children develop.

This is where philosophy becomes practice.

Froebel believed the ultimate goal of human development and education is to find what he called “Life Unity”—a state of harmony between the individual, nature, and the Creator. But how does a child actually move toward this unity?

Through a single, elegant process: making the “internal external and the external internal” through purposeful action.

Let me translate that into kitchen-table language.

What “Making the Inner External” Actually Means

Your four-year-old has thoughts, feelings, ideas, and understanding that exist only inside their head and heart. No one else can see them. Not you. Not their siblings. Not even the child themselves, really—these inner realities are fuzzy, half-formed, difficult to grasp.

Making the inner external means giving these invisible thoughts visible form.

When your child builds a tower with blocks, they’re not just stacking wood. They’re taking an inner concept—maybe “tall,” maybe “balance,” maybe “power,” maybe something they can’t yet name—and making it real in the physical world.

When they arrange colored shapes into a symmetrical pattern, they’re taking an inner sense of order, beauty, or rightness and making it visible.

When they draw a family portrait with everyone holding hands, they’re taking an inner feeling about connection and relationship and making it external.

Froebel viewed play as the highest phase of development specifically because it is the free representation of a child’s inner being.

Not controlled representation. Not directed representation. Free representation.

The child chooses what to make external. They choose how to express it. They choose when to stop and when to continue. The freedom is essential because it’s their inner world being expressed, not yours.

The Reverse Process: Making the Outer Internal

Now flip it around.

The world is enormous, complex, overwhelming. There are patterns everywhere—in nature, in buildings, in relationships, in how things work. But these patterns are too big, too abstract for a young child to grasp directly.

Making the outer internal means the child takes that overwhelming external world and brings it inside themselves where they can understand it.

How? By recreating it in play.

When your child builds a “house” with blocks, they’re taking the abstract concept of “shelter” and “home” and making it small enough to manipulate, understand, and control.

When they line up toy animals and create relationships between them, they’re taking the complex reality of social structures and internalizing it at a scale they can manage.

When they watch seeds grow in your garden, then recreate the growth sequence with drawings or gestures, they’re taking the external natural law of growth and making it internal—understood not just intellectually, but bodily, experientially.

By recreating the ordinary phenomena of life through their own play, children begin to internalize and understand the underlying laws of the universe.

This isn’t passive observation. It’s active reconstruction.

The Two-Way Street

Here’s what makes this profound:

The same activity does both things simultaneously.

When your child builds a tower, they’re:

- Making their inner concept of “tall” external (you can now see what they mean by tall)

- Making the outer law of gravity and balance internal (they’re learning how the world works)

When your child creates a symmetrical pattern, they’re:

- Making their inner sense of order external (you can see their aesthetic sense)

- Making the outer mathematical law of symmetry internal (they’re learning geometry without knowing it)

This is why Froebel insisted that through this active play, thinking awakens and the child’s relationship to the world truly opens up.

The child isn’t being told about the world. They’re actively discovering it through their own hands while simultaneously discovering themselves.

Action as the Bridge

Froebel had a specific term for this: being “active in thought” and turning that thinking into action is the very spring of all productive education.

Not thinking without action (abstract, disconnected). Not action without thinking (mechanical, meaningless).

Thinking-active. Active-thinking. The two become one process.

This is why Froebel’s famous Gifts and Occupations weren’t just toys or crafts. They were specifically designed to serve as the “third factor”—a mediator or bridge that allows this internalizing and externalizing to take place.

What the “Third Factor” Actually Does

Think of it this way:

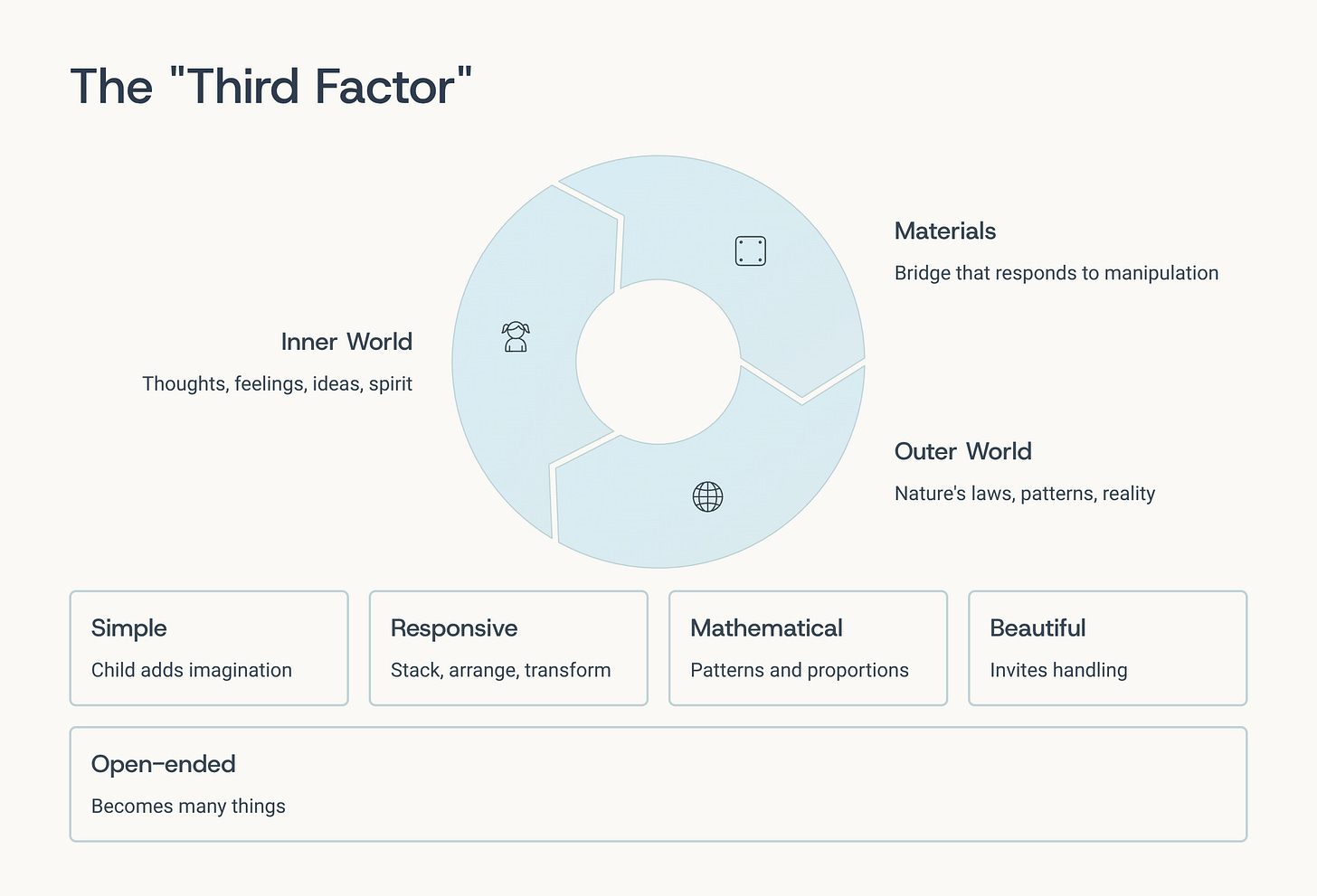

First factor: The child’s inner world (thoughts, feelings, ideas, spirit)

Second factor: The outer world (nature’s laws, mathematical patterns, social relationships, physical reality)

Third factor: Materials that respond to manipulation (blocks, shapes, art supplies, natural objects)

Without the third factor, the inner and outer stay separated. The child has thoughts but no way to make them visible. The world has laws but no way for the child to grasp them experientially.

The materials are the bridge.

But not just any materials. Froebel designed specific characteristics:

Materials should be:

- Simple enough that the child must add imagination

- Responsive to manipulation (they stack, arrange, combine, transform)

- Mathematical in structure (containing patterns, proportions, relationships)

- Beautiful in themselves (inviting handling and arrangement)

- Open-ended (capable of becoming many things)

Through these materials, children learn the “law of things” not through verbal instruction, but through the tangible experience of doing.

What This Looks Like at Each Age

Let me make this concrete with examples you’ll recognize.

Ages 3-5: The Foundation

What you see: Your three-year-old spends twenty minutes arranging blocks in a line, then picks them all up and does it again slightly differently.

What’s actually happening:

- Inner to outer: They have an inner sense of order, sequence, maybe even narrative (this block goes here, then this one, then this one). They’re making that invisible sequence visible and tangible.

- Outer to inner: They’re discovering that objects stay where you put them, that space has properties, that sequence has beginning and end. They’re internalizing spatial relationships.

Your role: Provide simple unit blocks (all the same size and shape) and protected time. Don’t ask “What are you making?” That interrupts the process. The making itself is the point.

Spielgaben connection: Gifts 3-6 (wooden blocks in various forms) were specifically designed for this age. But plain wooden unit blocks, or even cardboard boxes cut into uniform sizes, work the same way.

What you might notice: After weeks of this seemingly repetitive play, your child suddenly starts building vertical structures, or creating enclosures, or balancing blocks in increasingly complex ways. The inner understanding has been slowly forming; now it’s showing up in new external forms.

Ages 6-8: Increasing Complexity

What you see: Your seven-year-old creates symmetrical patterns with colored shapes, studies them, adjusts one piece, studies again, then carefully copies the pattern on paper.

What’s actually happening:

- Inner to outer: They have an inner sense of balance, beauty, mathematical relationship. They’re testing different external forms until one matches the inner sense of “rightness.”

- Outer to inner: They’re discovering the mathematical law of symmetry, color relationships, spatial organization. When they copy it to paper, they’re internalizing it at an even deeper level—the pattern is now inside them, not just in the materials.

Your role: Provide materials for pattern-making (pattern blocks, colored tiles, Spielgaben Forms of Beauty, or even cut paper shapes) and extended time—this isn’t a 15-minute activity. It’s 60-90 minutes of deep work.

What success looks like: The child becomes absorbed to the point where they don’t hear you call them. They make small adjustments repeatedly. They look at their creation from different angles. They might spontaneously explain their system to you—not because you asked, but because they’ve internalized it enough to articulate it.

Real example: Your daughter creates a symmetrical flower pattern using red, blue, and yellow shapes. She studies it. Adds another layer of petals. Studies again. Finally satisfied, she draws it on paper. Two days later, she notices symmetry in a real flower in your garden. She’s made the outer (mathematical symmetry) internal (she now sees it everywhere). When she creates her next pattern, it’s more complex—the inner understanding has grown.

Ages 9-12: Abstract Thinking Through Hands

What you see: Your ten-year-old builds an elaborate structure with blocks, then draws it from multiple angles, then tries to build it again from memory, then modifies the design based on what they learned.

What’s actually happening:

- Inner to outer: They have complex inner concepts—stability, proportion, aesthetic preference, maybe even architectural principles they’ve absorbed from observation. They’re testing these ideas in physical form.

- Outer to inner: They’re discovering principles of engineering, geometry, spatial relationships, even physics. When they draw from multiple angles, they’re internalizing three-dimensional thinking. When they rebuild from memory, they’re cementing the “law of things” deeply enough to reproduce without the model.

Your role: Provide materials that allow increasingly sophisticated building (advanced blocks, construction materials, craft supplies, tools). Protect substantial time—2-3 hours isn’t unusual for this kind of deep work. Ask questions that deepen thinking without providing answers: “What would happen if…?” “How did you decide…?” “What’s the relationship between…?”

What breakthrough looks like: They start explaining principles to you. “See, if I put the weight here, it needs a counterbalance there.” They’re not parroting what you taught—they discovered it through their hands, made it internal, and can now articulate it externally through language.

Real example: Your son becomes fascinated with bridge design. He builds bridge after bridge with blocks, testing how much weight each can hold. The structures get more complex. He starts drawing designs before building. One day he announces, “Triangles are the strongest shape because the weight gets distributed to all three points.” He discovered this not because you told him, but because he made the outer principle (structural engineering) internal through hundreds of attempts. Now when he sees a real bridge, he understands it from the inside out.

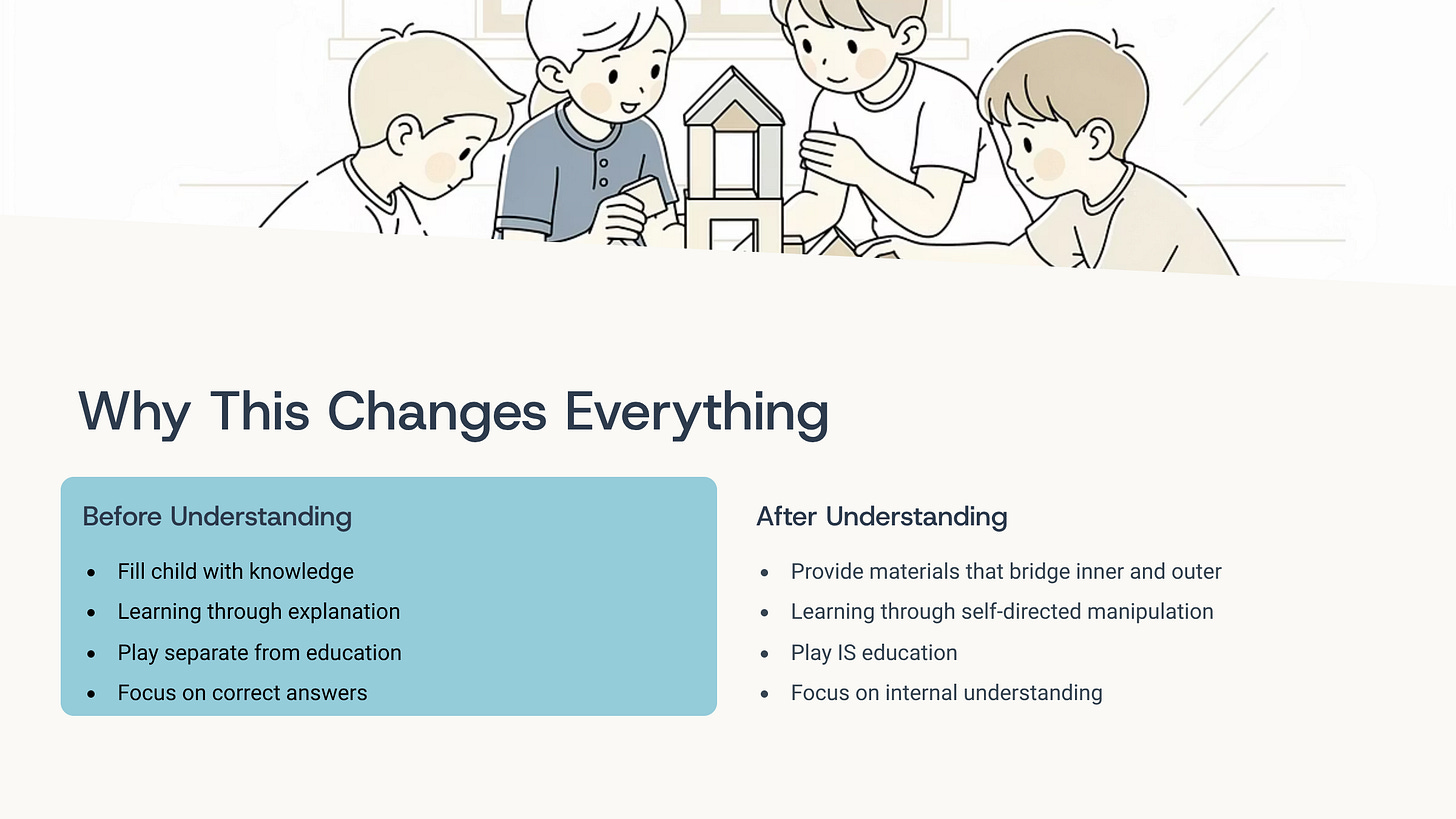

Why This Changes Everything

Once you understand that children develop through making the inner external and the outer internal, your entire approach to education shifts.

Before This Understanding

You think:

- My job is to fill my child with knowledge

- Learning happens through explanation and instruction

- Play is nice but education is separate

- The goal is correct answers

You do:

- Explain concepts verbally

- Correct mistakes immediately

- Move quickly from topic to topic

- Focus on measurable outcomes (worksheets completed, facts memorized)

After This Understanding

You think:

- My job is to provide the “third factor”—materials that bridge inner and outer

- Learning happens through self-directed manipulation of those materials

- Play is education; there’s no separation

- The goal is internal understanding that shows up in external competence

You do:

- Provide materials and time

- Observe what emerges without constant intervention

- Allow sustained focus on self-chosen projects

- Focus on the process (are they actively thinking? are they making inner concepts visible? are they internalizing outer patterns?)

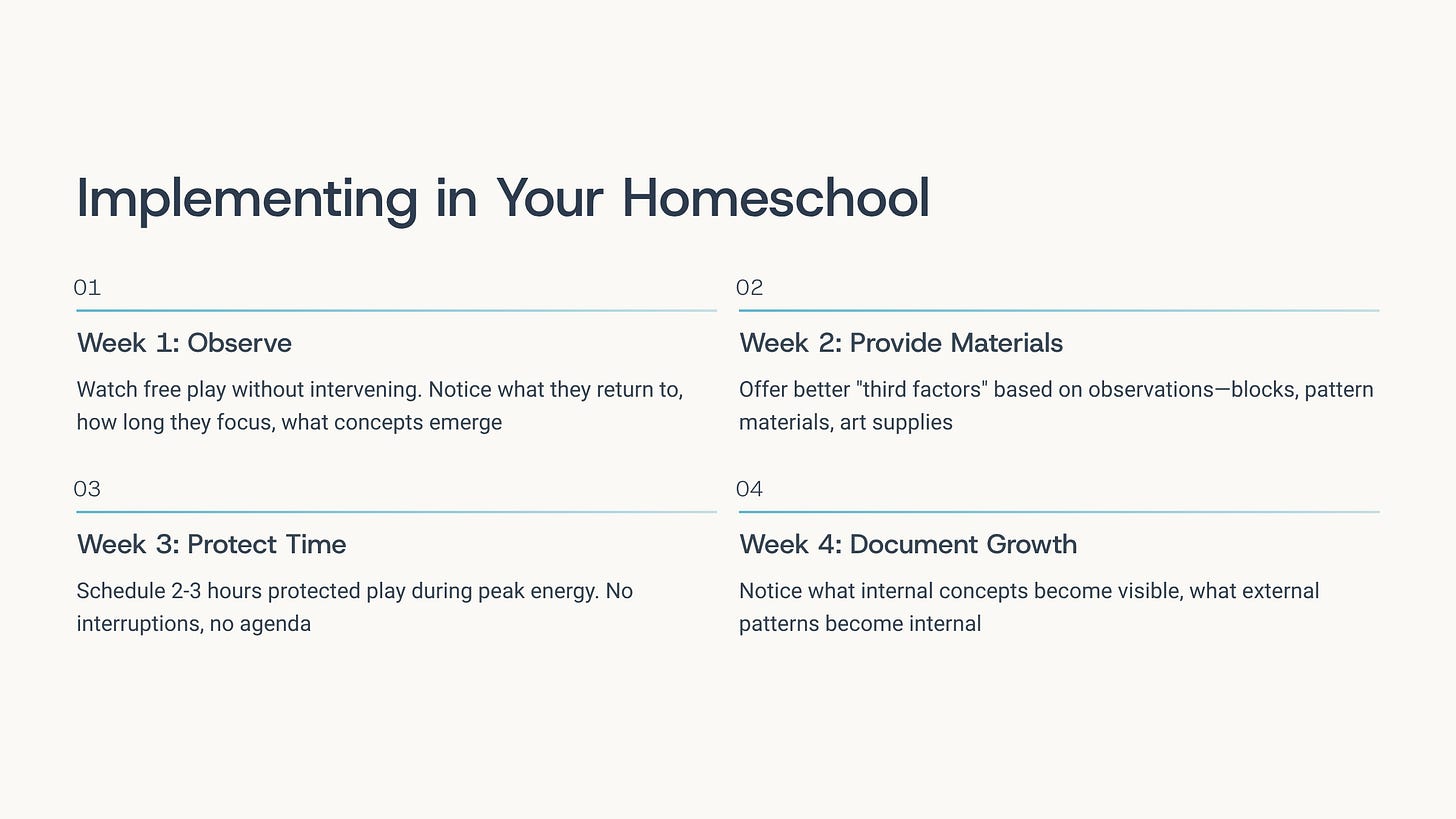

Implementing This in Your Homeschool

Here’s how to shift from filling children with facts to supporting the inner-external process.

Week 1: Observe the Process

Your task: Watch your children during free play time without intervening. Notice:

- What do they return to repeatedly?

- How long do they sustain focus?

- What are they making external (what inner concept is being expressed)?

- What are they making internal (what outer pattern are they trying to understand)?

Example observation: “Maya spent 45 minutes arranging rocks by size. First in a line, then in a circle, then in groups. She seemed to be working on something about relationships between big and small. This is making the outer mathematical concept of seriation internal.”

Week 2: Provide Better “Third Factors”

Your task: Based on what you observed, provide materials that better support the process they’re working on.

If they’re working on spatial relationships:

- Wooden blocks (unit blocks or Spielgaben Gifts 3-6)

- Boxes of various sizes

- Nesting containers

If they’re working on patterns and order:

- Pattern blocks or tangrams

- Spielgaben Forms of Life, Beauty, Knowledge

- Colored tiles or paper shapes

- Natural materials (shells, stones, leaves) for arrangement

If they’re working on representation and narrative:

- Simple figures (wooden peg dolls, felt animals)

- Building materials that can become structures

- Art supplies (paper, crayons, clay)

Key principle: Simpler is better. Materials that can become anything (generic blocks) support the process better than materials that can only be one thing (themed plastic toys).

Week 3: Protect Extended Time

Your task: Schedule 2-3 hours of protected play time during your children’s peak mental energy (usually morning).

Rules for this time:

- Materials are accessible

- No interruptions unless safety is at risk

- No “helpful” questions or improvements

- Projects can stay out overnight

- No agenda except to support the inner-external process

What to expect: First few days might be chaotic as children adjust to real freedom. By day 4-5, you’ll likely see deeper engagement. By week 2-3, you’ll see the kind of sustained, complex play that builds genuine understanding.

Week 4: Notice What Emerges

Your task: Document what you observe:

- What internal concepts are they making visible?

- What external patterns are they internalizing?

- How has the complexity evolved?

- What are they now able to articulate that they couldn’t before?

Example: “Day 1: Ben stacked blocks randomly. Day 5: Ben built an enclosure with a door. Day 10: Ben built a two-story structure with interior rooms. Day 15: Ben drew a floor plan before building. Day 20: Ben explained to his sister why her tower kept falling—he’s internalized principles of stability and can now make them external through language.”

Common Questions

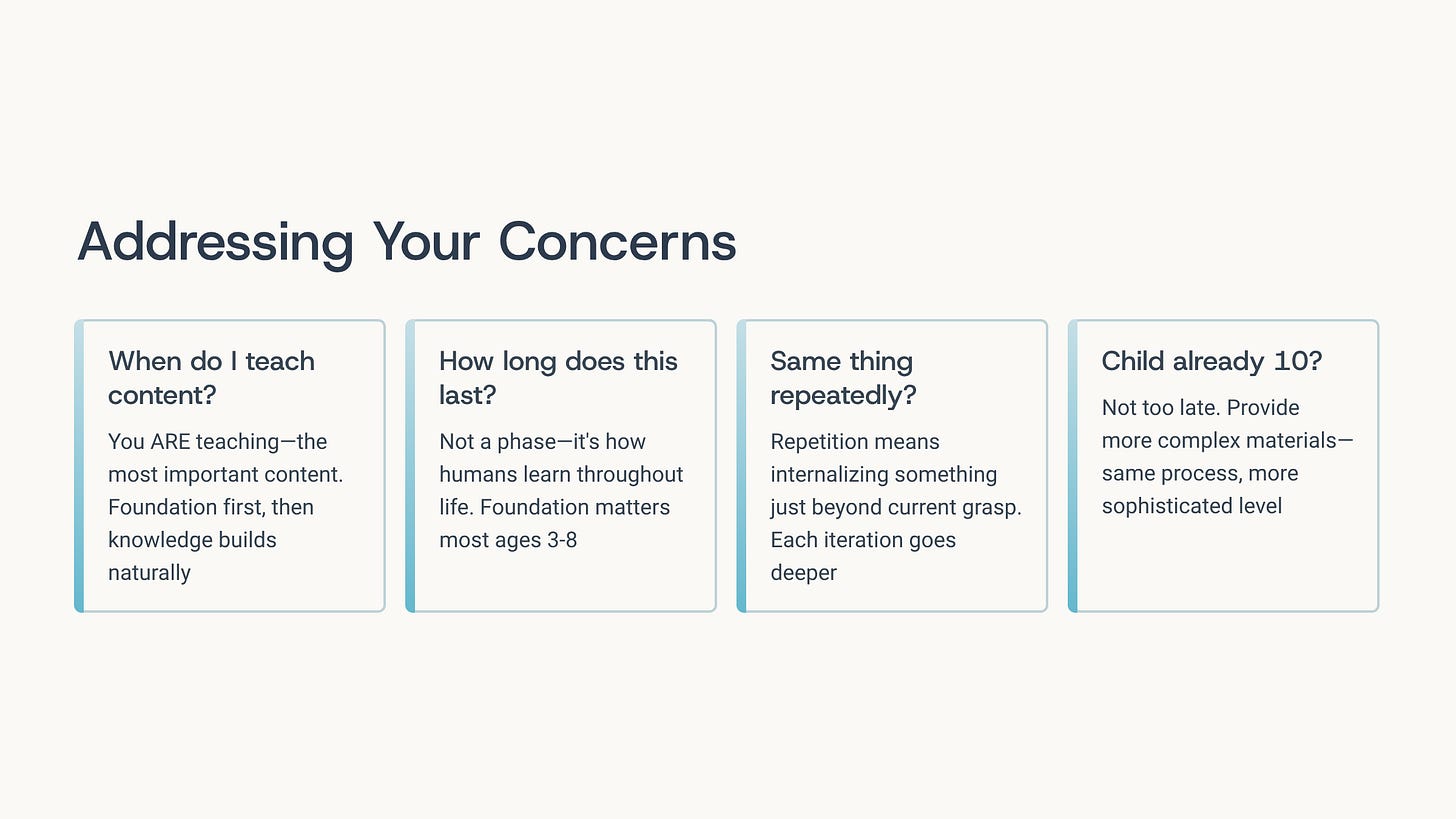

“But when do I teach actual content?”

You are teaching content—the most important content. The child who has deeply internalized mathematical relationships through block play will understand written mathematics easily when introduced later. The child who hasn’t internalized these relationships will struggle with abstract symbols no matter how much you drill.

Build the foundation first. The content knowledge builds naturally on top of it.

“How long does this phase last?”

This isn’t a phase you complete and move past. Making the inner external and the outer internal is how humans learn throughout life. But the foundation matters most in early childhood (ages 3-8), when children are primarily learning through direct manipulation rather than abstract symbol systems.

“What if my child just makes the same thing over and over?”

That’s exactly what you want to see. Repetition means they’re working on internalizing something just beyond their current grasp. When they’ve fully internalized it, they’ll naturally move to new challenges. Adults interrupt this process way too early because the repetition looks boring to us. To the child, each iteration is slightly different, slightly deeper.

“My child is already 10. Did I miss the window?”

No. Older children still need materials and time to make concepts external and internal, just at a more sophisticated level. Provide more complex materials (advanced building sets, craft supplies, tools, raw materials) and respect that their “play” looks different but serves the same developmental purpose.

The Gift of the “Third Factor”

Froebel called his materials “Gifts” for a reason.

Not because they were presents (though children do love them).

Because they gift the child with the means to bridge their inner and outer worlds.

The greatest gift you can give your children isn’t information downloaded into their heads. It’s the tools and time they need to discover themselves and the world through their own hands.

That’s Life Unity: the child finding harmony between their inner being, the natural world, and their Creator through active engagement with materials that respond to thought.

Everything else—reading, writing, mathematics, science, history, art—builds more solidly and more joyfully on this foundation.

Starting Today

If you remember nothing else from this article, remember this:

When your child is deeply engaged in building, arranging, creating, or manipulating materials, they’re not preparing for learning. They’re doing the most important learning there is.

Your job isn’t to interrupt it with “better” activities.

Your job is to protect it, support it, and trust it.

Make the inner external. Make the outer internal. Bridge the two with materials that respond to thinking hands.

That’s Fröbelian education in its purest form.

Coming Next: Now that we understand how children learn (making the inner external), we’ll explore one of Froebel’s key teaching methods: the “Law of Opposites.” How does comparing contradictory concepts—big and small, rough and smooth, straight and curved—help children build a deeper understanding of reality? And what does this look like in your daily homeschool rhythm?

Have you noticed your children making inner concepts external through their play? What patterns or ideas have emerged through their hands before they could articulate them in words? Reply and share your observations—these stories help all of us see the process more clearly.

P.S. The Spielgaben sets include Gifts (structured forms for free play) and Occupations (guided activities). Both serve as “third factors”—bridges between inner and outer. But the principle works with whatever you have: blocks, natural materials, art supplies, simple tools. Understanding the process matters infinitely more than owning specific products. Froebel would insist on this.

LEAVE A COMMENT