Holistic Education: Nurturing the Head, Heart, and Hand

You’ve probably seen it happen without knowing what to call it.

Your child is in the garden, hands deep in soil, planting seeds. She’s measuring how far apart to space them (maths). She’s wondering why some seeds need more sunlight than others (science). She’s feeling responsible for something alive (empathy). And she’s completely absorbed—no complaints, no “I’m bored,” no checking out.

That’s not just gardening. That’s holistic education in action. And a man named Friedrich Fröbel built his entire philosophy around it over 200 years ago.

In our previous posts, we explored Fröbel’s remarkable life story and how his “Law of Opposites” builds a child’s understanding of the world. Today, we’re unpacking what might be his most powerful idea for homeschooling families: educating the Head, Heart, and Hand as one inseparable whole.

This isn’t abstract philosophy. It’s the difference between a child who memorises multiplication tables and forgets them by summer—and a child who understands numbers because she’s touched them, built with them, and shared them with someone she cares about.

Where Fröbel Got the Idea: The Pestalozzian Foundation

Fröbel didn’t develop this concept in isolation. In the early 1800s, he studied under the Swiss social reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, who argued that genuine education must engage three inherent “powers” within every child:

The Head — intellectual power. Thinking, reasoning, understanding.

The Hand — physical or bodily strength. Doing, making, moving.

The Heart — moral and emotional self-power. Feeling, caring, connecting.

Pestalozzi saw all three as essential. But Fröbel took it further.

He didn’t just want to develop each power separately. He wanted to unify them into what he called “Life Unity”—a state where the child’s thinking, doing, and feeling work together in complete harmony with nature and the world around them.

Think of it this way: Pestalozzi said “train all three.” Fröbel said “you can’t truly train one without the other two.”

This distinction matters enormously for homeschoolers. It means that a maths lesson that only engages the head is, by Fröbel’s standard, incomplete. And an art project that only engages the hands is missing two-thirds of its potential.

The Complete Human: Three Dimensions, One Child

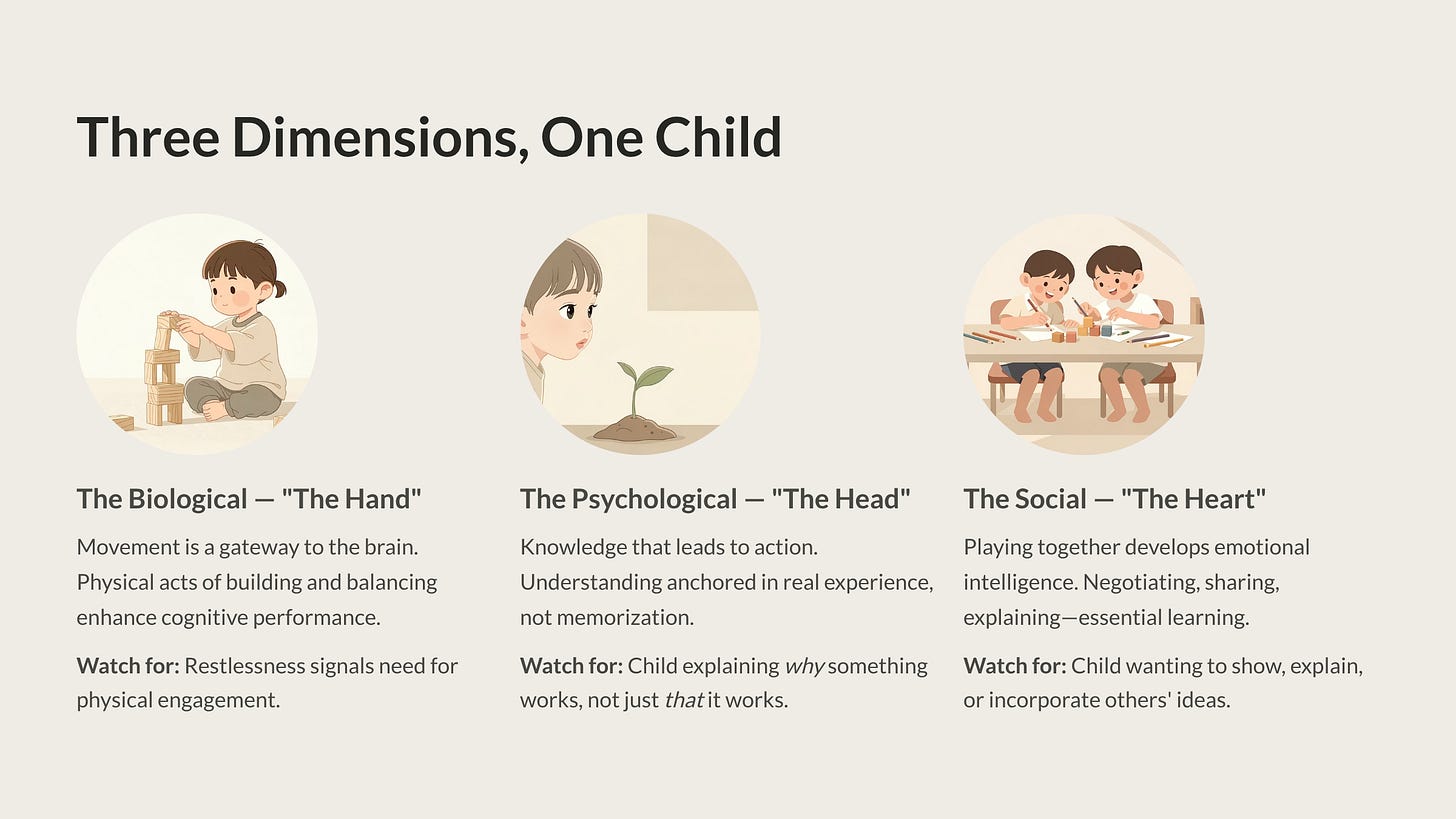

Fröbel viewed every human being as a complex totality. Not a brain to be filled. Not a body to be trained. Not a heart to be moulded. All three, woven together in what he understood as biological, psychological, and social dimensions.

Here’s how he understood each—and what it means for your homeschool:

The Biological — “The Hand”

This includes physical growth, movement, and the deep urge children have to do things with their bodies. Fröbel recognised something neuroscience has since confirmed: movement is a gateway to the brain.

When your child builds a tower with Spielgaben wooden blocks, she isn’t just exercising her fingers. The physical act of stacking, balancing, and adjusting is directly enhancing her cognitive performance. The hand teaches the head.

This is why worksheets alone fall short for young learners. A child who physically groups objects into sets of three understands multiplication differently—more deeply—than one who only sees “3 × 4 = 12” on paper.

What to watch for: Children who are restless, fidgety, or “can’t sit still” during lessons aren’t misbehaving. Their biological dimension is screaming for engagement. Give it something meaningful to do, and the head and heart follow.

The Psychological — “The Head”

This encompasses perception, sensation, feeling, and thinking. But Fröbel’s goal wasn’t to create children who simply know things. He wanted what he called the “thinking-active human being”—a person who turns internal thoughts into external actions.

Not just “I know that plants need water.”

But “I’m going to water the garden because I understand what will happen if I don’t.”

Knowledge that leads to action. Understanding that becomes doing. That’s the kind of intellectual development Fröbel was after, and it’s the kind that sticks—because it’s anchored in real experience, not memorised from a page.

What to watch for: When your child starts explaining why something works rather than just that it works, you’re seeing psychological development in motion. “The tall tower fell because it’s heavier on top” is a child connecting thinking to observation. Celebrate it.

The Social — “The Heart”

Fröbel believed the child is a “member of a larger whole.” Education isn’t complete if it only sharpens the mind and strengthens the body but leaves the child unable to communicate, cooperate, and care.

This is where playing together becomes essential. When children negotiate rules during a game, share materials during a building project, or take turns explaining what they’ve created, they’re developing social and emotional intelligence that no textbook can teach.

For homeschoolers, this is a powerful reminder: collaborative play sessions—with siblings, co-op groups, or neighbourhood friends—aren’t a break from learning. They are the learning.

What to watch for: A child who builds something and immediately wants to show it to someone, explain it, or incorporate another person’s idea is exercising the heart dimension. A child who adjusts their creation to make room for a sibling’s addition is learning something no worksheet can assess.

The “Dividing Spirit” Fröbel Fought Against

Here’s where Fröbel’s critique of traditional schooling hits uncomfortably close to home—even today.

He called it the “dividing spirit.”

He argued that conventional schools “killed” subjects by breaking them into disconnected fragments. Maths in one box. Science in another. Art over here. Physical activity squeezed into a separate timeslot. Each piece severed from the others, and all of them severed from real life.

Fröbel saw this as deeply damaging. When you separate thinking from doing, or recognising from acting, you create a fractured learning experience. The child might pass the test, but they haven’t truly understood anything—because understanding requires the whole person.

His solution was radical for his time and still radical for ours: playing, learning, and working must remain an “undivided whole of life.”

Whether a child is tending a garden, building structures with the Spielgaben Gifts, composing a song, or solving a problem, they should be simultaneously engaging their physical strength, their intellectual reasoning, and their emotional care for life.

That’s not three separate lessons. It’s one experience, complete and alive.

A moment of honesty for homeschool parents: Many of us left the traditional school system precisely because of this “dividing spirit.” We could feel that something was wrong with chopping learning into disconnected 45-minute blocks. Fröbel gave that instinct a name over 180 years ago. Trust it.

What This Means for Your Homeschool

If you take one thing from Fröbel’s holistic philosophy, let it be this:

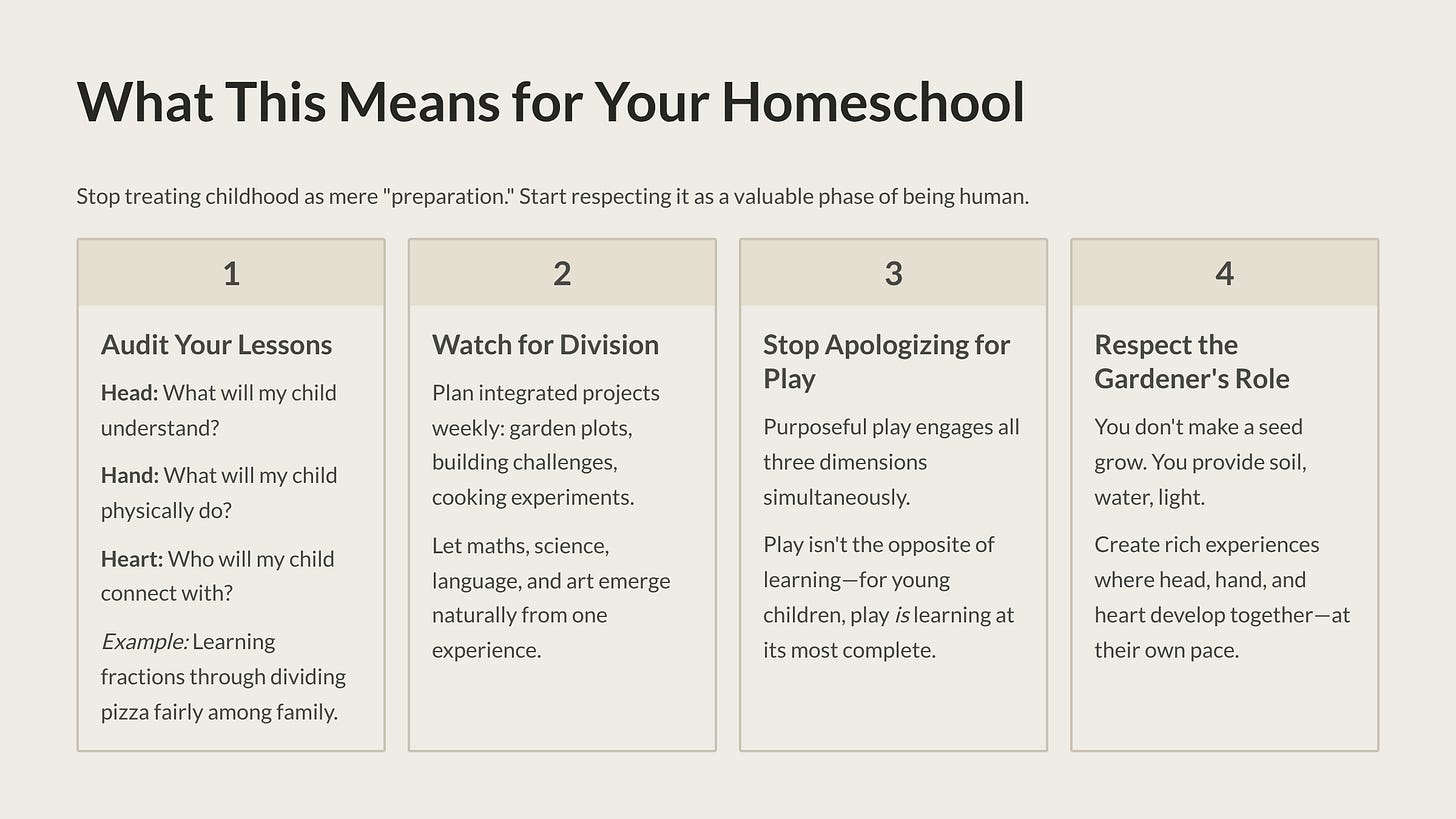

Stop treating childhood as mere “preparation” for the future. Start respecting it as a valuable and irretrievable phase of being human.

Your child isn’t a rough draft of an adult. They are a complete person, right now, who learns best when their whole self is invited into the process.

Here’s what that looks like practically:

1. Audit Your Lessons for All Three Dimensions

Next time you plan an activity, ask yourself three questions:

Head: What will my child think about, figure out, or understand?

Hand: What will my child physically do, touch, build, or move?

Heart: Who will my child connect with, care about, or communicate with?

If you can answer all three, you have a Fröbelian lesson. If one is missing, it’s not ruined—but look for a way to bring it in.

Example: Your child is learning about fractions.

- Head: Understanding that 1/2 + 1/4 = 3/4

- Hand: Using Spielgaben wooden tiles or cutting a homemade pizza into equal pieces

- Heart: Dividing the pizza fairly among family members, discussing what “equal share” means when someone is hungrier

That ten-minute pizza exercise hits all three dimensions. A worksheet asking “what is 1/2 + 1/4?” hits only one.

2. Watch for the “Dividing Spirit” in Your Own Planning

It’s easy to fall into the trap of scheduling “maths time” and “science time” and “art time” as separate, disconnected blocks—especially if you’re using a structured curriculum.

Try this instead: once a week, plan a single project that refuses to be divided. A garden plot. A building challenge. A cooking experiment. A nature walk with sketching.

Let the maths, science, language, and art emerge naturally from one integrated experience.

You’ll be amazed at how much ground you cover without a single worksheet.

3. Stop Apologising for Play

If Fröbel were alive today, he’d have one message for homeschool parents who feel guilty about “too much play”: don’t.

When your child plays with purpose—building, experimenting, creating, collaborating—they are engaging all three dimensions simultaneously. Play isn’t the opposite of learning. For young children, play is learning at its most complete.

This doesn’t mean unstructured chaos. Fröbel’s play was intentional. The Spielgaben Gifts, for instance, are carefully designed to invite specific kinds of exploration. But within that structure, the child leads—and when they lead with their hands, head, and heart together, genuine understanding follows.

4. Respect the Gardener’s Role

Fröbel’s favourite metaphor wasn’t the teacher as instructor. It was the teacher as gardener. Our task is to perceive the whole personality of the child and provide the right conditions for their unique talents to grow.

You don’t make a seed grow. You give it soil, water, and light. You protect it from harsh conditions. And then you step back and watch.

The same is true for your child. Your job isn’t to pour knowledge into them. It’s to create rich, whole experiences where their head, hand, and heart can develop together—at their own pace, in their own way.

Looking Ahead: From Philosophy to Practice

Over the past several weeks, we’ve explored the philosophical foundations of Fröbel’s approach—his life story, his understanding of play, the Law of Opposites, and now his holistic vision of Head, Heart, and Hand.

Starting next week, we shift gears.

We’re beginning our Masterclass on the Fröbel “Gifts”—the carefully designed sequence of learning materials that Fröbel created to put his philosophy into children’s hands. Literally.

We’ll start with the very first Gift: The Ball.

It sounds simple. It’s anything but. The Ball is Fröbel’s introduction to movement, colour, and the very first opposites a child can grasp. It’s where the entire journey begins.

If you’ve ever wondered why your toddler is obsessed with throwing, rolling, and chasing balls—Fröbel had the answer two centuries ago. And next week, we’ll share it with you.

LEAVE A COMMENT