How to Know When Your Child Has Truly Mastered a Math Concept (Without Tests)

You’ve just spent three weeks on addition with regrouping. Your child can solve the problems. She gets the right answers most of the time. The workbook page is finished.

So you move to the next lesson.

Two months later, when that same concept appears in a word problem, you watch your child stare at it blankly. “I don’t remember how to do this.”

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: completion is not mastery. And traditional tests don’t measure what matters most.

This is why so many homeschool parents feel caught in a perpetual cycle of “we covered this already” followed by “why doesn’t she remember?” You’re measuring the wrong thing. You’re looking for answers when you should be looking for understanding.

If you’re using manipulatives for math—whether Spielgaben, Cuisenaire rods, base-ten blocks, or objects from around your house—you already have the best assessment tool available. You just need to know what you’re looking for.

Why “Getting the Right Answer” Isn’t Enough

Let me show you what surface-level learning looks like.

A seven-year-old solves 8+5 by counting on his fingers. He gets 13. You smile. He writes it down. You move on.

Six weeks later, you give him 9+5. He counts on his fingers again, starting from scratch. There’s no recognition that this problem is structurally identical to dozens he’s solved before. He’s not building on previous knowledge—he’s starting fresh every single time.

This is procedural knowledge without conceptual understanding. And it’s heartbreakingly common.

Here’s what deep understanding looks like instead:

That same seven-year-old encounters 8+5. He pauses, then says: “Well, 8+2 is 10, and I still have 3 more, so it’s 13.” Or: “5+5 is 10, and 3 more is 13.” Or even: “I know 10+5 is 15, so 8+5 must be 2 less, which is 13.”

Same answer. Completely different cognitive process.

The first child has memorized a procedure. The second child understands number relationships and can manipulate them flexibly. When new challenges appear—word problems, multi-digit addition, even algebra years from now—guess which child has the foundation to succeed?

Traditional tests can’t measure this distinction. A multiple choice question about 8+5=? looks identical for both children. A timed fact test rewards the memorizer and penalizes the thinker.

But manipulatives reveal everything.

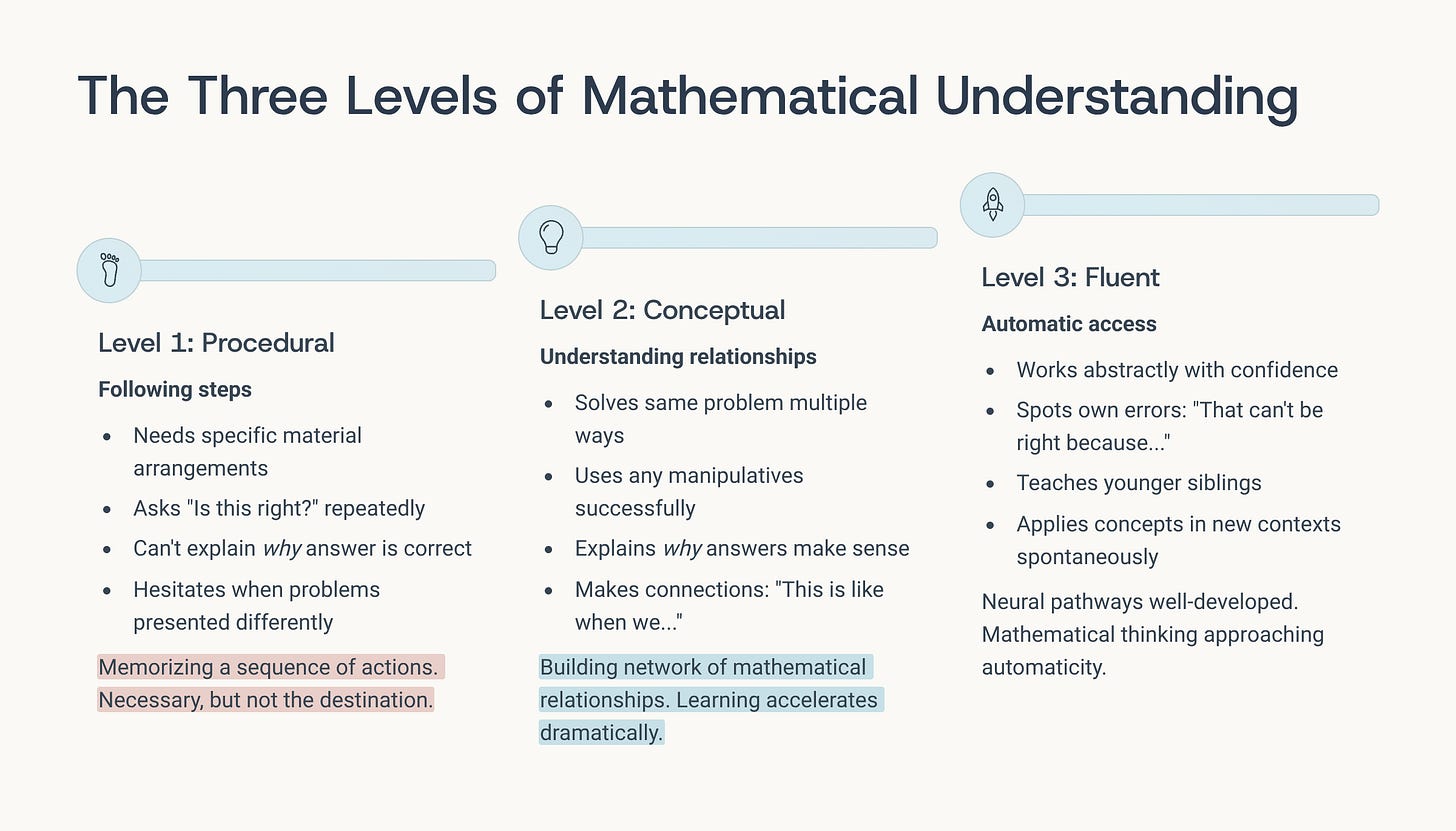

The Three Levels of Mathematical Understanding

Before we talk about assessment, you need to understand the progression every child moves through when learning any mathematical concept. This isn’t theoretical—this is observable reality in your homeschool.

Level 1: Procedural (Following Steps)

Your child can solve the problem if you set it up correctly. She needs the manipulatives arranged in a specific way. She follows the steps you showed her yesterday.

She can do 15-7 with base-ten blocks if you hand her one ten-rod and five unit cubes. She can tell you the answer. But if you give her two ten-rods and ask her to show 15-7, she’s lost. The procedure doesn’t transfer to a new setup.

What you see:

- Dependency on specific materials or arrangements

- Hesitation when problems are presented differently

- “Is this right?” asked multiple times during one problem

- Inability to explain why an answer is correct

- Successful completion of one problem doesn’t lead to faster solution of the next similar problem

What’s happening in her brain: She’s memorizing a sequence of actions. This is necessary and normal. This is where everyone starts. But this isn’t where anyone should stay.

Level 2: Conceptual (Understanding Relationships)

Your child understands what the numbers represent and how they interact. He can solve the same problem multiple ways because he sees the underlying mathematical relationships.

Give him 15-7 with any manipulatives—blocks, buttons, Spielgaben gifts, even drawings—and he can solve it. He might decompose 7 into 5 and 2, subtract the 5 from 15 to get 10, then subtract the 2 to get 8. Or he might count up from 7 to 15. Or he might know that 7+8=15, so 15-7 must be 8.

What you see:

- Flexible problem-solving approaches

- Ability to use different manipulatives for the same concept

- Explaining why an answer makes sense, not just how to get it

- Making connections: “This is like when we did…”

- Solving problems faster as pattern recognition develops

What’s happening in his brain: He’s building a network of mathematical relationships. Numbers aren’t isolated facts—they’re connected ideas. This is when learning accelerates dramatically.

Level 3: Fluent (Automatic Access)

Your child has internalized the concept so thoroughly that she can work abstractly. She doesn’t need manipulatives for every problem because she can visualize the mathematical relationships.

She sees 15-7 and immediately knows it’s 8, not from memorization but from deep pattern recognition. She can also tell you that 150-70=80, that 1.5-0.7=0.8, and can explain why these problems are mathematically identical.

What you see:

- Quick, confident responses to familiar problem types

- Choosing to work abstractly, but returning to manipulatives when confused

- Spotting errors in her own work: “Wait, that can’t be right because…”

- Teaching younger siblings: “Let me show you how this works”

- Applying the concept in completely new contexts without prompting

What’s happening in her brain: The neural pathways are so well-developed that mathematical thinking is approaching automaticity. This is where you want every foundational concept to land before you move forward.

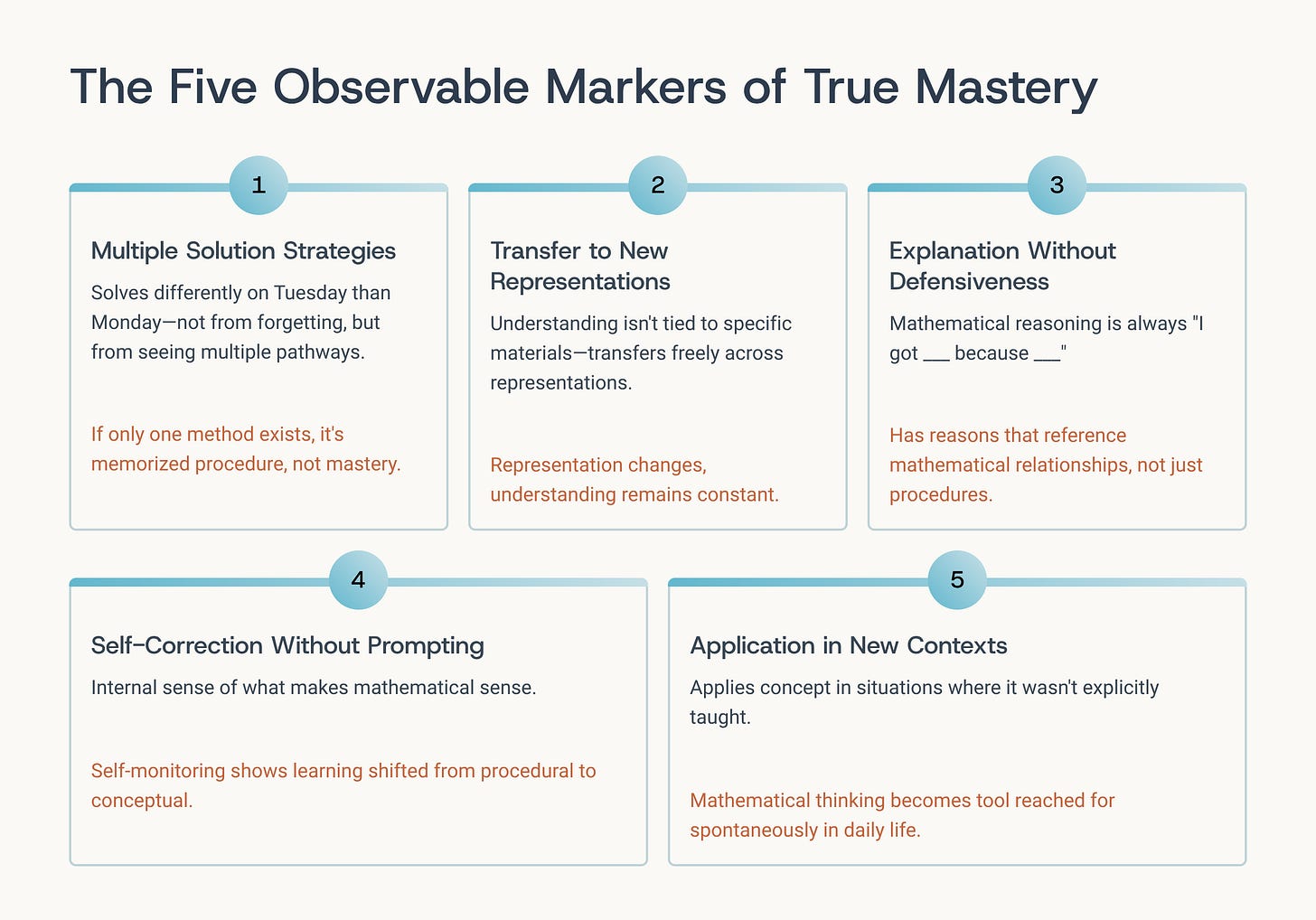

The Five Observable Markers of True Mastery

Forget the test. Forget the workbook page. Here’s what to watch for instead.

Marker 1: Multiple Solution Strategies

Set up a problem and walk away. Come back in five minutes.

A child who has truly mastered a concept will solve it differently on Tuesday than she did on Monday. Not because she forgot the “right way,” but because she sees multiple pathways to the solution and is experimenting with efficiency.

What this looks like:

Addition: Your child solves 7+8 by making ten (7+3=10, plus 5 more), then solves 6+9 by doubling (6+6=12, plus 3 more), then solves 8+8 by saying “I just know that one—it’s 16.”

Subtraction: She solves 13-5 by counting back, then solves 13-7 by counting up (”7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13—that’s 6 jumps”), then solves 13-8 by using her knowledge that 8+5=13.

Multiplication: He solves 6×4 with arrays one day (6 rows of 4), by skip counting the next (4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24), and by doubling two days later (3×4=12, so 6×4 is double that).

If your child has only one way to solve a problem, she hasn’t mastered it—she’s memorized a procedure.

How to test this: Present the same problem three days in a row without comment. Does your child use different approaches? Does he choose the most efficient method? Can he explain why he switched strategies?

Marker 2: Transfer to New Representations

True understanding isn’t tied to specific materials. It transfers freely across different representations.

If your child learned place value with base-ten blocks but can’t explain it with money, drawings, or bundled craft sticks, the learning is fragile. It’s attached to one particular manipulative rather than to the mathematical concept itself.

What this looks like:

Fractions: Your child learned 1/4 + 1/4 = 1/2 with fraction circles. Then you give her Spielgaben’s square tiles and ask her to show the same thing. She can do it. You draw a rectangle and ask her to shade the same relationship. She can do it. You present a word problem about pizza. She can solve it.

Multiplication: He learned 3×5 by building arrays with cubes. You ask him to draw it. He draws 3 rows of 5 circles. You ask him to show it by skip counting on a number line. He marks 5, 10, 15. You ask him to describe it in a story. “If I have 3 bags with 5 apples each…”

The representation changes, but the understanding remains constant.

How to test this: Once your child demonstrates competence with the primary manipulative you’ve been using, switch to something completely different. Pattern blocks to drawings. Base-ten blocks to money. Arrays to number lines. If understanding transfers smoothly, mastery is developing.

Marker 3: Explanation Without Defensiveness

Ask your child to explain how she got her answer.

If the only defense of the answer is “Because that’s what I got” or “Because you showed me yesterday,” understanding is shallow. Mathematical reasoning is always “I got ___ because ___.”

What this looks like:

Surface level: “What’s 12-7?” “Five.” “How do you know?” “I counted.” [Shows no understanding of why counting works or what 12-7 actually means]

Deep understanding: “What’s 12-7?” “Five.” “How do you know?” “Well, I know 7+5=12, so if I take 7 away from 12, I’m left with 5. Or I could think about it like 12-2=10, then 10-5=5.” [Demonstrates multiple relationship pathways]

A child with genuine understanding doesn’t just have answers—she has reasons. And those reasons reference mathematical relationships, not just procedures.

How to test this: Ask “How did you know?” or “Can you show me your thinking?” after every third or fourth problem. You’re not looking for the right words—you’re listening for evidence that your child sees the mathematical structure beneath the numbers.

If she can explain her thinking clearly, she’s building conceptual understanding. If she can’t, she may be following procedures she doesn’t truly understand yet.

Marker 4: Self-Correction Without Prompting

Children who truly understand a concept can spot their own errors because they have an internal sense of what makes mathematical sense.

When your child writes 8+9=18, pauses, and says “Wait, that’s not right—8+9 should be less than 20 but more than 16,” he’s demonstrating mastery. He knows what the answer should look like before he calculates it.

What this looks like:

Without mastery: Gets an answer, looks to you for confirmation, accepts your correction without understanding why the answer was wrong, makes the same type of error again tomorrow.

With mastery: Gets an answer, evaluates whether it’s reasonable, catches obvious errors (”I got 25, but 13+7 should be around 20, so I must have made a mistake”), explains the error (”Oh, I counted this block twice”), fixes it independently.

This self-monitoring is one of the most powerful indicators that learning has shifted from procedural to conceptual.

How to test this: When your child makes an error, don’t point it out immediately. Instead, ask: “Does that answer make sense to you?” or “Is there a way to check your work?” Children with deep understanding will often catch their own mistakes when prompted to reflect. Children still at the procedural level will look at you blankly.

Marker 5: Application in New Contexts

The ultimate test of mastery is whether your child can apply the concept in situations where it wasn’t explicitly taught.

You spend three weeks on area using manipulatives and grid paper. Then you’re planting a garden. Your child spontaneously says, “We should measure how many square feet we have so we know how many plants fit.” That’s transfer. That’s mastery.

What this looks like:

Fractions: You’ve been working with fraction circles. Your child is helping bake and says, “We need 3/4 cup but we only have a 1/4 measuring cup, so we need to fill it three times.”

Multiplication: You’ve practiced arrays. Your child is setting up chairs for a family gathering and says, “If we need 24 chairs and we put them in 4 rows, each row should have 6 chairs.”

Place value: You’ve worked with base-ten blocks. Your child is counting money and groups the dollar bills into stacks of ten without being asked, saying “It’s easier to count this way.”

When mathematical thinking becomes a tool your child reaches for spontaneously in daily life, you know the learning has rooted deeply.

How to test this: You can’t really manufacture this one. But you can stay alert for it. When you notice spontaneous mathematical thinking—in conversation, during play, while solving real problems—that’s your evidence that mastery is solidifying.

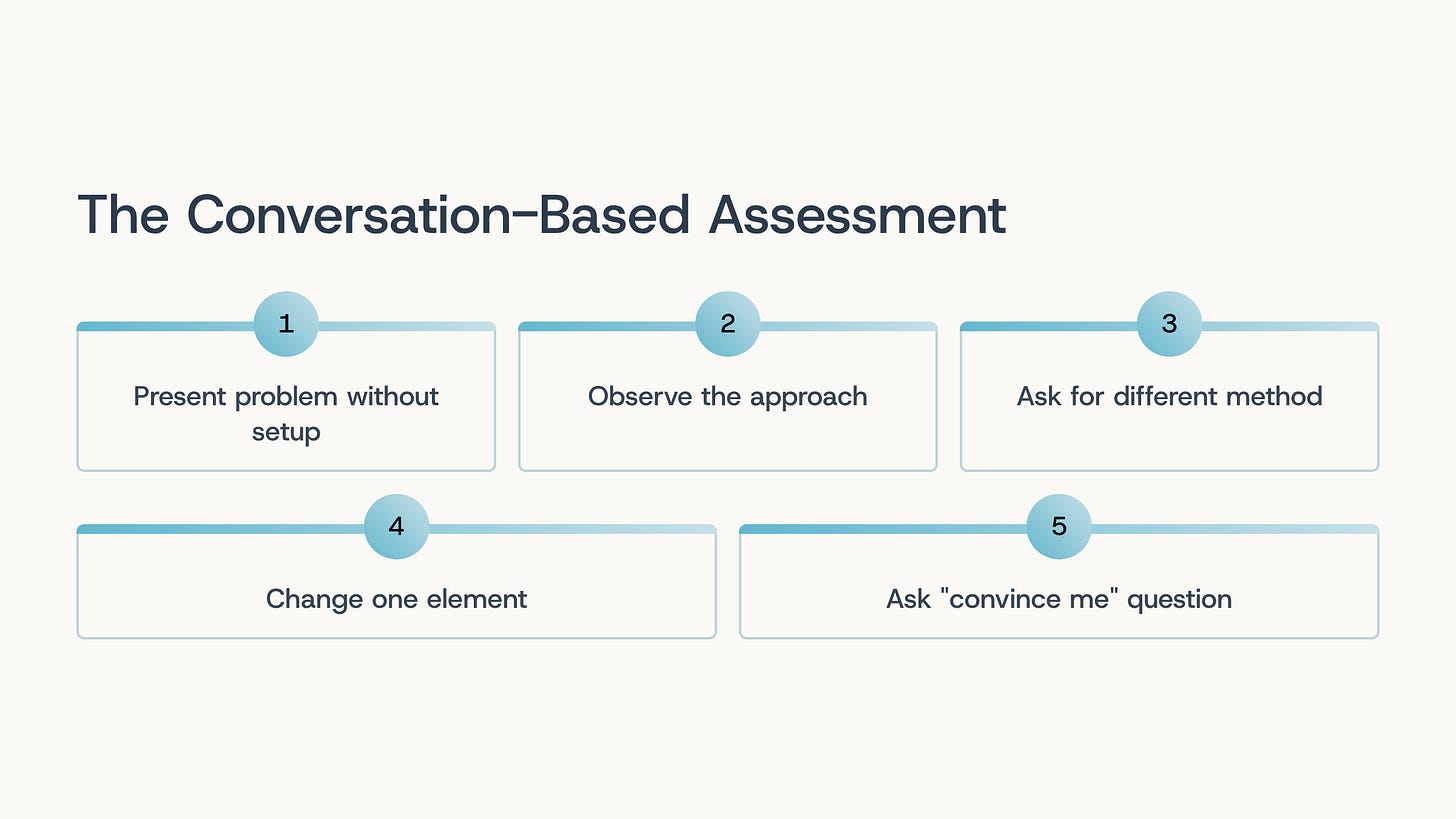

The Conversation-Based Assessment That Works Better Than Tests

Here’s a simple protocol you can use weekly to gauge where your child actually is. It takes 10 minutes and reveals far more than any written test.

Step 1: Present the problem without setup

Don’t prepare the manipulatives. Don’t remind your child how to do it. Just present the problem in whatever context feels natural.

“If I have 24 cookies and I want to put them into bags of 6, how many bags do I need?”

Then be quiet. Watch what your child does first.

Step 2: Observe the approach

Does he immediately reach for manipulatives? Good—he knows he needs to think concretely about this.

Does he stare at it uncertainly? He may not recognize this as a division problem yet.

Does he start drawing? Excellent—he’s building a representation.

Does he solve it mentally and explain his reasoning? He may be ready to work more abstractly.

Step 3: Ask for a different method

After your child solves the problem one way, say: “Interesting! Is there another way you could figure that out?”

If he’s stuck on one method, he’s still at the procedural level. If he can show you two or three approaches, conceptual understanding is developing.

Step 4: Change one element

“What if I had 25 cookies instead of 24?”

A child with surface learning will start completely over. A child with deeper understanding will say, “Oh, then I’d have 4 bags and 1 leftover” because he can modify his existing solution rather than rebuilding from scratch.

Step 5: Ask the “convince me” question

“How do you know that’s right? Could you explain it to someone who didn’t understand?”

This is where the depth of understanding becomes unmistakable. Can your child articulate the mathematical reasoning behind the solution? Or is the defense simply “because I did it”?

What you’re listening for:

- References to mathematical relationships (”because 6 four times is 24”)

- Connection to previously learned concepts (”it’s like when we divided the blocks”)

- Multiple justifications (”I know it’s right because I can multiply back: 4×6=24”)

- Clear explanations that demonstrate actual understanding, not memorized scripts

If you have these conversations regularly—even just once a week—you’ll know exactly where your child is. Not based on how many problems they completed or what percentage they got correct, but based on the quality of their mathematical thinking.

When to Move Forward (And When to Wait)

This is the question that haunts every homeschool parent: “Are we ready for the next concept, or should we stay here longer?”

Here’s your decision framework.

Move forward when:

- Your child demonstrates at least 3 of the 5 mastery markers consistently

- She can explain her thinking clearly on most problems

- He chooses efficient strategies more often than not

- Understanding transfers to at least 2 different representations

- You see spontaneous application in daily life

Notice that “completed all the workbook pages” isn’t on this list. Neither is “got 80% on a quiz.” Those measure completion, not comprehension.

Stay put when:

- Your child relies on the same procedure every time

- He can’t explain why an answer is correct beyond “I counted”

- She needs you to set up each problem

- Manipulatives are removed and panic sets in

- The same errors appear repeatedly without self-correction

This doesn’t mean drilling the same problems until your child is bored to tears. It means finding new contexts, new manipulatives, new applications for the same underlying concept until it clicks at a deeper level.

The pacing paradox:

Going slowly now means going faster later. A child who truly masters addition with regrouping will fly through multi-digit subtraction, multiplication, and eventually algebra. A child who barely memorized the procedure will struggle with each new concept because the foundation is shaky.

You’re not behind. You’re building something that lasts.

Practical Mastery Checks for Common Concepts

Let me give you specific, observable markers for concepts you’re likely teaching right now.

Single-digit addition/subtraction (K-2):

- Makes ten flexibly (7+8 becomes 7+3+5)

- Recognizes fact families (knows 6+7=13 means 13-7=6)

- Solves mentally within 20 without finger counting

- Explains: “8+5 is 13 because 8+2 makes 10, and 3 more makes 13”

Place value (1-3):

- Represents any number to 1000 with multiple manipulatives

- Explains: “245 is 2 hundreds, 4 tens, and 5 ones”

- Compares numbers by place value (”347 is bigger than 329 because even though 2 is less than 4 in the tens place, 3 hundreds is more than 3 hundreds—wait, they’re the same in hundreds, so I look at tens, and 4 tens is more than 2 tens”)

- Regroups mentally: “ten tens is the same as one hundred”

Multiplication/division (3-5):

- Knows multiplication as repeated addition, arrays, and scaling

- Switches between multiplication and division: “If 7×8=56, then 56÷7=8”

- Uses properties: “6×4 is the same as 4×6” or “5×12 is the same as 5×10 plus 5×2”

- Estimates before calculating: “7×9 should be close to 70 because 7×10=70”

Fractions (3-6):

- Represents fractions with multiple models (circles, bars, area, number line)

- Compares fractions conceptually: “3/8 is less than 1/2 because 4/8 would be half”

- Knows equivalent fractions: “2/4 is the same as 1/2 because I can fold it”

- Explains: “1/3 + 1/3 = 2/3 because I’m putting together two pieces that are each one-third of the whole”

If your child can do these things, you’re ready to move forward—even if the workbook isn’t finished.

What to Do When Mastery Seems Stuck

Sometimes you’ve spent weeks on a concept and your child still hasn’t reached mastery. You’re both frustrated. The manipulatives aren’t helping anymore. What now?

First, check the prerequisite concepts.

Often, apparent difficulty with a concept is actually a gap in earlier learning. A child struggling with multiplication might not have truly mastered skip counting or addition. A child confused by fractions might need more work with division and equal parts.

Go back one step. Make sure the foundation is solid before building higher.

Second, change the representation completely.

If you’ve been using Spielgaben’s counting boards and your child is still stuck, switch to something entirely different. Draw pictures. Use food. Go outside and use sidewalk chalk. Build with LEGO.

Sometimes the manipulative itself becomes the obstacle. The child has associated the concept so tightly with one specific material that changing representations forces fresh thinking.

Third, make it a game.

Pressure inhibits learning. Playfulness enhances it.

Turn the concept into a challenge, a race against the timer, a teaching game where your child explains it to a stuffed animal. Remove the “we’re doing math now” formality and see what happens.

Fourth, take a strategic break.

If you’ve been working on double-digit multiplication for six weeks with minimal progress, put it aside. Go back to concepts your child has mastered. Build confidence. Do math that feels successful.

Then return to the difficult concept in two weeks. Often, the brain has been processing in the background. The breakthrough comes after the break, not during the grind.

Fifth, consider developmental readiness.

Some concepts require cognitive development that simply hasn’t happened yet. Trying to teach formal fractions to a six-year-old is fighting biology. Backing off for six months and trying again often results in immediate success.

This isn’t failure. This is honoring how children actually learn.

The Long Game

Ten years from now, your child won’t remember whether you finished the second-grade math book in second grade or third grade.

But she will carry the mathematical foundation you’re building right now into every quantitative challenge she faces for the rest of her life.

The student who truly understands place value becomes the adult who catches accounting errors.

The child who can explain why 3/4 + 1/4 = 1 becomes the carpenter who calculates measurements without a calculator.

The kid who learned to check whether an answer makes sense becomes the professional who spots flawed reasoning in research papers.

This is why mastery matters more than coverage. Why deep understanding beats wide exposure. Why you should pace according to your child’s comprehension, not some arbitrary scope and sequence chart.

You’re not teaching math. You’re teaching mathematical thinking. And that requires patience, careful observation, and trust in the process.

So watch your child with manipulatives in hand. Listen to her explanations. Notice when she applies concepts spontaneously. Pay attention to the five markers.

And when you see true understanding developing—flexible thinking, clear reasoning, confident application—move forward with confidence.

You’re building something beautiful. Something that lasts.

Your child’s mathematical journey is unique. If you’re using Spielgaben materials, you already have a comprehensive set of manipulatives that support learning from counting through algebra—designed specifically to help children progress from concrete to abstract thinking at their own pace. But regardless of what materials you use, these mastery markers remain constant. Trust the process. Trust your child. And trust yourself to recognize deep understanding when you see it.

LEAVE A COMMENT