The Day My Daughter Spotted the Manipulation (And I Realized Schools Never Taught Her How)

My 10-year-old came home from school last Thursday unusually quiet.

“Sophie wants to come over this weekend,” she finally said. “But she said if I don’t let her, she’ll invite Emma instead and won’t be my friend anymore.”

I felt my jaw tighten. Sophie had pulled this move before—the ultimatum disguised as friendship.

“What do you think about that?” I asked.

She shrugged. “I guess I have to say yes?”

That’s when it hit me: We’d taught her to manage money. We’d taught her to negotiate for herself. But she has not learned how to recognize when someone was manipulating her.

She saw Sophie’s threat as a normal request, not a manipulation tactic. She thought she had no choice. She was ready to say yes to something she didn’t want because she couldn’t see the pattern.

And here’s the terrifying part: This same manipulation shows up everywhere as kids get older—peer pressure, advertising, relationships, social media, salespeople, even authority figures who use emotional tactics instead of logic.

Schools don’t teach kids to spot these patterns. They teach critical thinking about books and historical events, not about the manipulation happening in the hallway and on their phones.

The Problem: Schools Teach Critical Thinking About The Wrong Things

Here’s what happens in most classrooms:

Teachers ask kids to analyze why Shakespeare’s characters made certain choices. They teach them to identify bias in historical sources. They assign persuasive essay analysis for literary techniques.

All valuable skills. All focused on text and theory.

But nobody’s teaching them to analyze the manipulation happening in real time:

The friend who says: “If you don’t send me your homework answers, we are not friends any longer.”

The ad that says: “Only cool kids have this. Don’t be the only one without it.”

The classmate who says: “Everyone else is going to the party. Why are you being so lame?”

The manipulative adult who says: “You’re so mature for your age. You can handle this.”

Kids learn to analyze texts critically, but not people or situations. They graduate knowing how to write five-paragraph essays about propaganda in World War II, but they can’t spot the propaganda in their own lives.

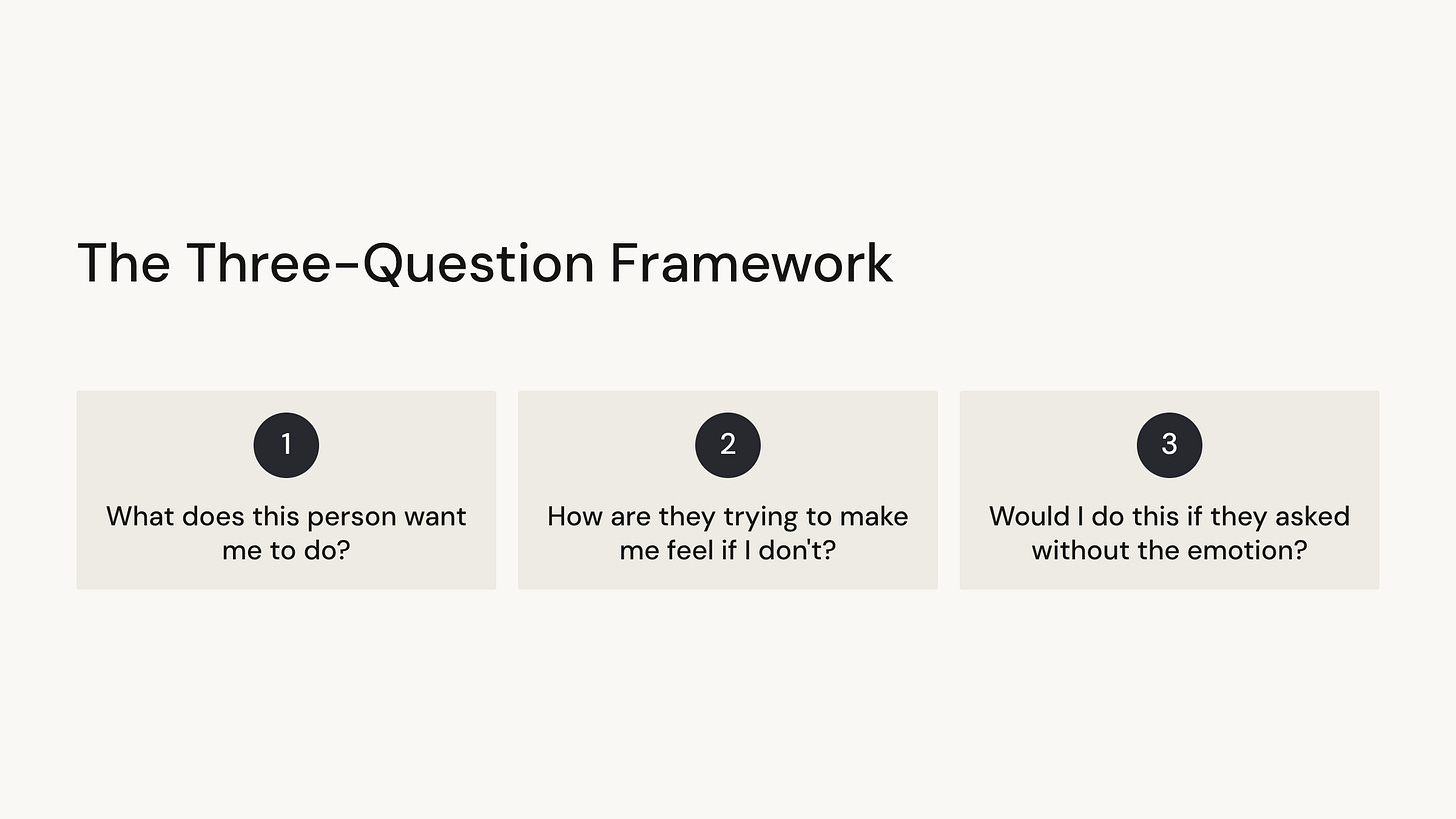

The Solution: The Three-Question Framework

After the Sophie incident, I taught my daughter three simple questions to ask herself anytime someone wants her to do something:

1. What does this person want me to do?

(Name it clearly—not just “be friends,” but the specific action)

2. How are they trying to make me feel if I don’t do it?

(Guilty? Scared? Left out? Stupid? Unimportant?)

3. Would I do this if they asked without the emotion?

(Remove the manipulation, keep the request)

With Sophie, we walked through it:

“What does Sophie want you to do?”

“Let her come over this weekend.”

“How is she trying to make you feel if you don’t?”

She thought about it. “Like… I’ll lose her as a friend. Like I’m being mean.”

“Okay. If Sophie had just asked ‘Can I come over this weekend?’ without the threat, would you want to say yes?”

Long pause. “Probably not. I kind of wanted to just read and have a quiet weekend.”

That’s when her face changed. She’d seen the pattern.

“She’s trying to make me feel bad so I’ll say yes even though I don’t want to!”

Yes. Exactly.

What Actually Happened

I didn’t tell my daughter what to do about Sophie. Instead, I asked: “So what’s your decision?”

She thought about it. “I’m going to tell her I already have plans this weekend. And if she says she won’t be my friend anymore, then she’s not actually a good friend.”

She did. Sophie didn’t react well at first—lots of dramatic texts about how my daughter was “being mean” and “didn’t care about friendship.”

But here’s what happened:

By Monday, Sophie was back to normal, acting like nothing happened. The manipulation didn’t work, so she stopped using it.

By the following weekend, Sophie asked again—this time without the threat. My daughter said yes. They had a great time.

The bigger transformation? Two weeks later, my daughter came home and said: “I think that Tik Tok video I watched this week was trying to manipulate me into buying stuff.”

She’d spotted the pattern on her own. In a completely different context. That’s when I knew this was working.

The three questions had become her filter for everything—friendships, advertising, peer pressure, even sometimes checking whether I was being fair in my parenting decisions (which, honestly, keeps me sharper too).

Give these three questions a try with your child, and please share your experience with us.

Author

Jim – Chief Editor of Spielgaben and a dad with two beautiful children

LEAVE A COMMENT