The First Gift: The Ball — Your Child’s First “Gymnastics Coach”

Hand a toddler a ball.

Watch what happens. They squeeze it. They drop it. They throw it (probably at your face). They chase it across the room. They pick it up and do it all again.

Now watch more closely.

That squeeze? They’re learning about resistance and give. That drop? They’ve just discovered gravity. That throw? Cause and effect. That chase? Motor planning, spatial awareness, balance, and determination—all firing at once.

You thought they were playing. They’re conducting physics experiments.

Friedrich Fröbel knew this over 180 years ago. After careful consideration, he chose the simple ball as the very first object in his entire educational sequence—not because it was easy, but because it is, in his words, “a picture of the universe and an image of completeness.”

Welcome to the first lesson in our Fröbel Gifts Masterclass. And it starts with the most ordinary extraordinary object your child will ever hold.

Why a Ball? Why First?

Of all the possible starting points, Fröbel could have chosen blocks. He could have chosen shapes, tiles, or rings. He chose a ball.

Here’s why: the ball has no edges, no corners, no beginning, and no end. It looks the same from every angle. It’s the most unified, complete form in nature. For Fröbel, it was the perfect first “mediator” between the child and the natural world.

He encouraged parents to help children see the ball shape everywhere in their environment—from the tiniest seed to the radiant sun and moon in the sky. A dewdrop on a leaf. A berry on a bush. A bubble floating through the air. Every one of these is a sphere, and every one connects the child to the same fundamental form they’re holding in their hand.

This wasn’t just poetic thinking. Fröbel believed that when a child recognises the same shape in their toy and in the world around them, they begin to feel a deep sense of harmony—what he called “Life Unity”—between themselves and nature. That feeling of connection becomes the emotional foundation for all future learning.

For your homeschool, this means the ball isn’t just your child’s first toy. It’s their first window into the idea that the world has patterns, and those patterns can be understood.

The Ball as “Gymnastics Coach”

One of Fröbel’s most charming descriptions of the First Gift is as a child’s “gymnastics coach.” Not a toy to be passively observed—a trainer that demands physical response.

The ball embodies the principle of movement. Even the slightest impulse sets it in motion. And here’s the magic: a child doesn’t just watch a ball move. They move with it.

When the ball bounces, the child instinctively wants to bounce too. When it spins or flies through the air, the child reaches, jumps, or spins alongside it. When it rolls away, the child crawls, toddles, or runs after it. The ball leads; the child follows. And in following, the child develops physical strength, dexterity, balance, and motor coordination—without a single instruction from you.

This is what Fröbel meant when he talked about “self-active” learning. The ball doesn’t need to be explained. It invites. It provokes. It challenges. And the child responds with their whole body.

Think about it this way: You could spend twenty minutes trying to get a two-year-old to practise reaching, grasping, throwing, and balancing. Or you could hand them a ball and let the ball do the coaching.

Fröbel chose the coach.

Learning Physics Before They Can Spell It

While we often see a game of catch as simple fun, Fröbel saw a tool of education that introduces the child to the laws of the physical world. And he was right.

Through the soft wool or cloth balls of the First Gift—traditionally provided in the six colours of the rainbow—the child begins to grasp complex scientific concepts through direct sensory experience:

Three Dimensions of Space

Suspend a ball on a string. Swing it left and right. Now forward and back. Now up and down. Your child has just experienced all three dimensions of physical space—not as a diagram in a textbook, but as a felt, seen, lived experience.

They don’t know the words “horizontal,” “vertical,” or “depth” yet. But their body knows. And when those words arrive years later, they’ll land on a foundation that’s already built.

Gravity and Momentum

Drop the ball. It falls. Every time. Without exception.

Throw it up. It comes back down. Every time.

Roll it along the floor. It slows and stops.

Push it harder. It goes further before stopping.

Your child is learning about gravity, momentum, friction, and force—not through explanation, but through repetition and observation. They’re forming expectations about how the physical world behaves. And when those expectations are confirmed again and again, something powerful happens: they begin to trust that the world is predictable and knowable.

That trust is the emotional bedrock of scientific thinking.

Cause and Effect

This is perhaps the most important lesson the ball teaches. A specific push creates a specific result. A gentle roll stays close. A hard throw goes far. A sideways nudge sends the ball in a new direction.

Every interaction with the ball reinforces the idea that actions have consequences—predictable, repeatable consequences. This is the seed of logical reasoning, problem-solving, and eventually, mathematical thinking.

When your five-year-old says, “If I push it harder, it goes further,” they’re articulating a hypothesis. They’re doing science. With a ball.

The Gateway to Thinking

Fröbel designed the First Gift balls to be soft—made from wool or cloth—so they cannot hurt the child or their surroundings. This is a deliberate choice, not a safety afterthought.

A hard ball that breaks a vase teaches the child fear and hesitation. A soft ball that bounces harmlessly off everything teaches the child to explore without consequence. Fröbel wanted fearless exploration, because fearless exploration is where thinking begins.

As the child plays “self-actively” with the ball, their thinking awakens in stages:

Comparison: “This ball is red. That ball is blue. They’re different.” This is the very beginning of analytical thinking—noticing differences and similarities.

Pattern recognition: “When I drop the ball, it always falls down. Never up.” The child is identifying a reliable pattern, which is the foundation of all scientific reasoning.

Prediction: “If I roll the ball toward the wall, it will bounce back.” The child is forming a hypothesis based on prior experience. They’re not just reacting to the world anymore—they’re anticipating it.

Experimentation: “What happens if I throw it higher? Harder? With a spin?” The child is deliberately varying conditions to test outcomes. This is the scientific method, performed by a three-year-old in a living room.

All of this from a ball. No lesson plan required.

Bringing the First Gift Into Your Homeschool

Here’s how to use the First Gift intentionally at different ages, whether you have a Spielgaben set or are working with what you have at home.

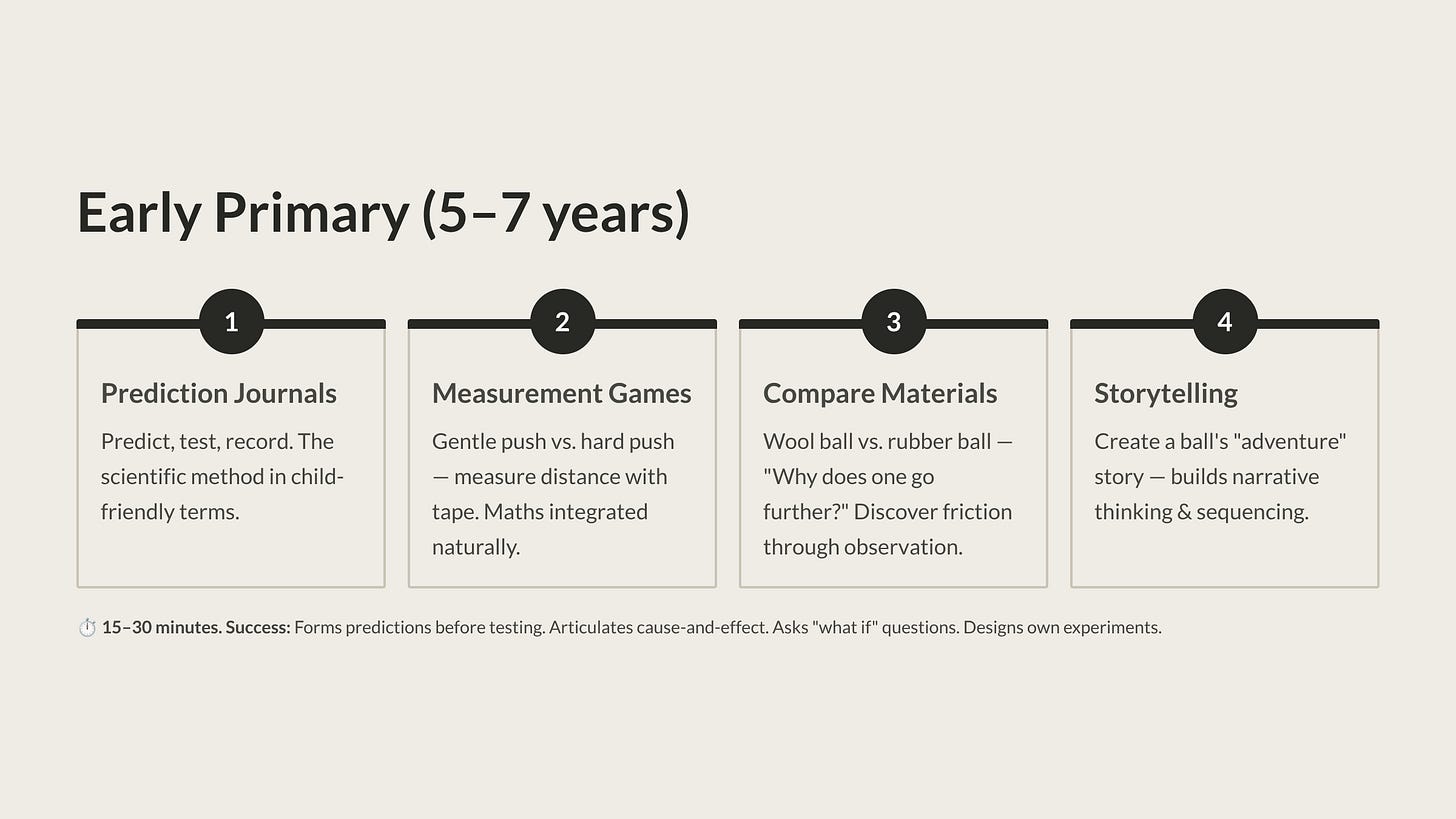

For Babies and Toddlers (6 months – 2 years)

Materials: Soft wool or knitted balls in solid, bright colours. The Spielgaben First Gift provides six rainbow-coloured yarn balls on strings, but you can also use soft fabric balls or even rolled-up socks in different colours for a start.

Activities:

- Dangling and tracking. Hold a ball on a string in front of your baby and swing it gently side to side. Watch their eyes follow. This builds visual tracking, which is a precursor to reading.

- Hiding and revealing. Place the ball behind your back. Bring it out. “Where did the ball go? Here it is!” This builds object permanence—the understanding that things exist even when you can’t see them.

- Rolling back and forth. Sit facing your toddler and roll the ball between you. This is their first experience of turn-taking, communication, and shared play. Head, Heart, and Hand—all three, in one simple game.

Time commitment: 5–10 minutes at a time is plenty. Follow your child’s interest, not a timer.

What success looks like: Your child anticipates the ball’s return. They reach for it before it arrives. They laugh when it appears from behind your back. They begin to roll it back to you deliberately rather than randomly.

For Preschoolers (3–5 years)

Materials: The same soft balls, plus a string for suspension experiments.

Activities:

- Colour naming and sorting. “Can you find the blue ball? Can you put all the warm colours together?” This builds colour recognition, vocabulary, and classification skills.

- Pendulum play. Hang a ball from a string on a doorframe or chair back. Push it gently. Let your child observe the swing. “What happens when you push it harder?” This introduces pendulum motion, arc, and the concept that force affects distance.

- Ball hunt in nature. Take a walk and challenge your child to find “ball shapes” in the environment. Berries. Pebbles. Seeds. Dandelion puffs. The moon at night. This is Fröbel’s original exercise—connecting the Gift to the natural world—and children love it.

- Directional language. Roll or swing the ball and narrate: “The ball goes up. Now it comes down. It swings left. Now right. It rolls forward. Now backward.” Your child absorbs spatial vocabulary through lived experience rather than memorisation.

Time commitment: 10–20 minutes, or as long as interest lasts.

What success looks like: Your child begins using directional words on their own. They predict what the ball will do before it does it. They find sphere shapes in the world without being prompted. They start inventing their own ball games with rules.

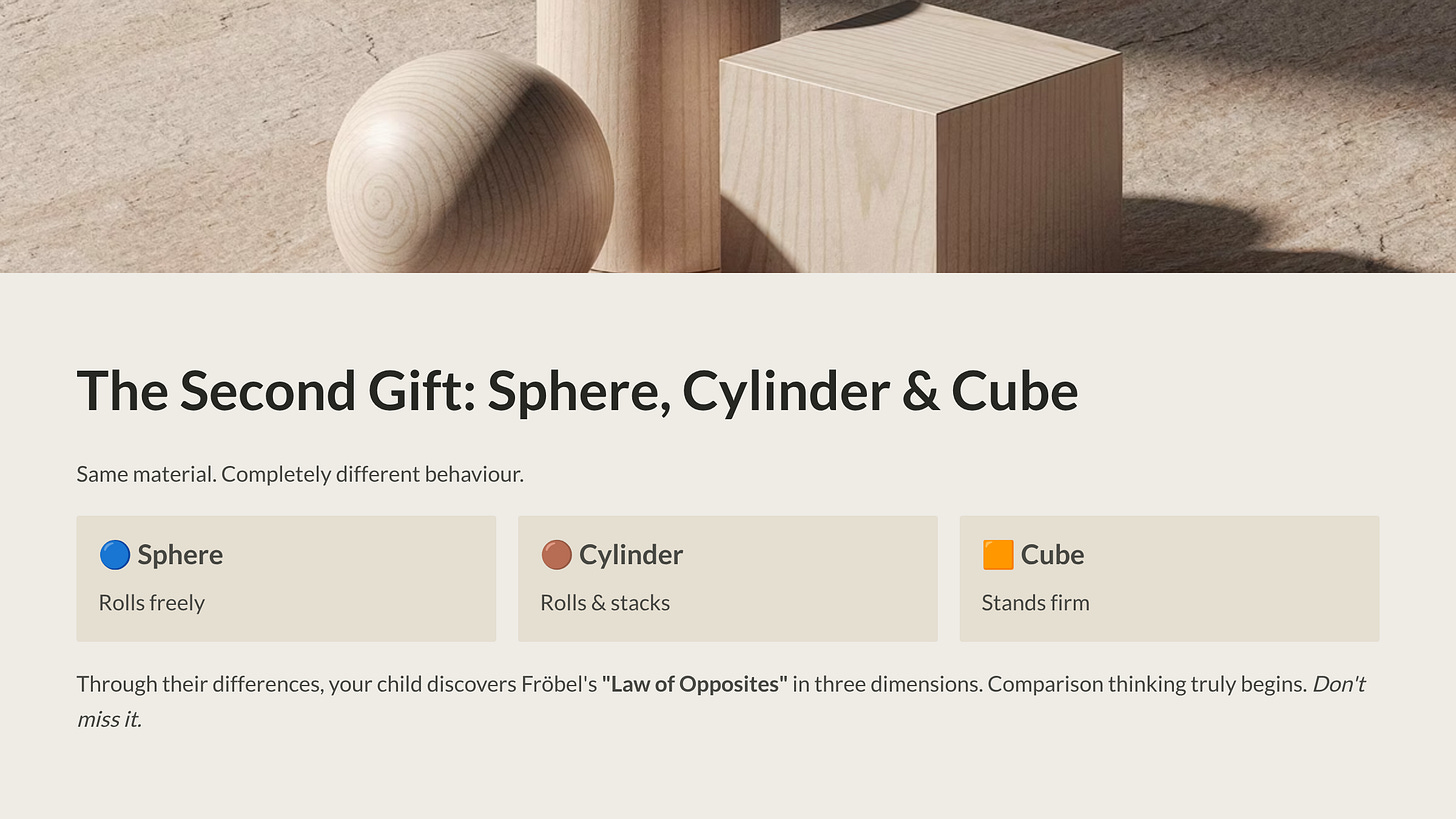

For Early Primary (5–7 years)

Materials: Soft balls plus harder balls (tennis balls, bouncy balls) for comparison.

Activities:

- Prediction journals. Before each experiment, ask your child to predict what will happen. “If I drop the soft ball and the hard ball at the same time, which lands first?” Write or draw the prediction, then test it. This formalises the scientific method in child-friendly terms.

- Measurement games. “How far does the ball roll when you push it gently? When you push it hard?” Use a tape measure or a piece of string to compare distances. This integrates maths naturally.

- Comparison of materials. Roll a wool ball and a rubber ball on the same surface. “Why does one go further?” Introduce the concept of friction through observation, not definition.

- Storytelling with balls. Ask your child to create a story about a ball’s “adventure”—where it rolls, what it bumps into, where it ends up. This builds narrative thinking and sequencing while staying connected to the Gift.

Time commitment: 15–30 minutes per session.

What success looks like: Your child forms predictions before testing. They articulate cause-and-effect relationships in their own words. They ask “what if” questions and design their own experiments. They connect ball play to concepts they encounter in books or everyday life.

Respect the Ball

It’s tempting to dismiss the First Gift as too simple. A ball? Really? My child needs something more advanced.

Fröbel would gently disagree.

By respecting the ball as a serious educational tool, we provide our children with their first “gymnastics” for both the body and the mind. The ball teaches movement, physics, pattern recognition, prediction, and social connection—all without a single worksheet, screen, or instruction manual.

And it does something else, too. It teaches your child that learning is joyful. That the world is knowable. That their actions matter.

That’s not a small beginning. That’s everything.

Coming Next Week

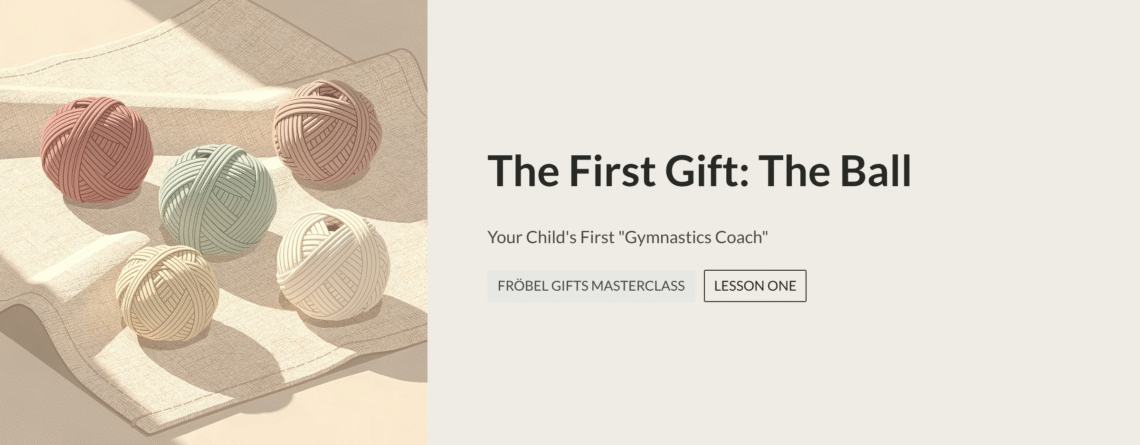

We move from the soft, unified ball to the Second Gift, where things get exciting—and challenging. Your child will encounter three contrasting forms: the Sphere, the Cylinder, and the Cube.

Same material. Completely different behaviour. And through those differences, your child will discover Fröbel’s “Law of Opposites” in three dimensions.

The Second Gift is where comparison thinking truly begins. Don’t miss it.

This is part of our ongoing Fröbel Gifts Masterclass at the Spielgaben Homeschool Series. If you’re new here, start with our earlier posts on Fröbel’s life story, the Law of Opposites, and Holistic Education: Head, Heart, and Hand.

LEAVE A COMMENT