The Magic of the Second Gift: Helping Children Distinguish Reality from Appearance

Place a wooden sphere and a wooden cube side by side on a table.

Now nudge them both with your finger.

The sphere rolls away immediately—smooth, effortless, unstoppable until something gets in its way. The cube? It barely moves. It sits there, stubborn and solid, as if it has decided that this spot on the table is exactly where it belongs.

Your child just witnessed something profound: two objects, made from the same material, the same size, behaving in completely opposite ways. And if you hand them both and ask “why?”—watch their face. You can almost see the thinking start.

This is the Second Gift. And it’s where Fröbel’s educational genius shifts from movement into meaning.

In our last post, we explored the First Gift—the soft ball—and how it serves as a child’s first “gymnastics coach.” Today, we step from soft wool into solid wood, from a single form into three contrasting ones: the sphere, the cylinder, and the cube.

These aren’t just shapes. They’re a lesson in how the world works—and how things aren’t always what they seem.

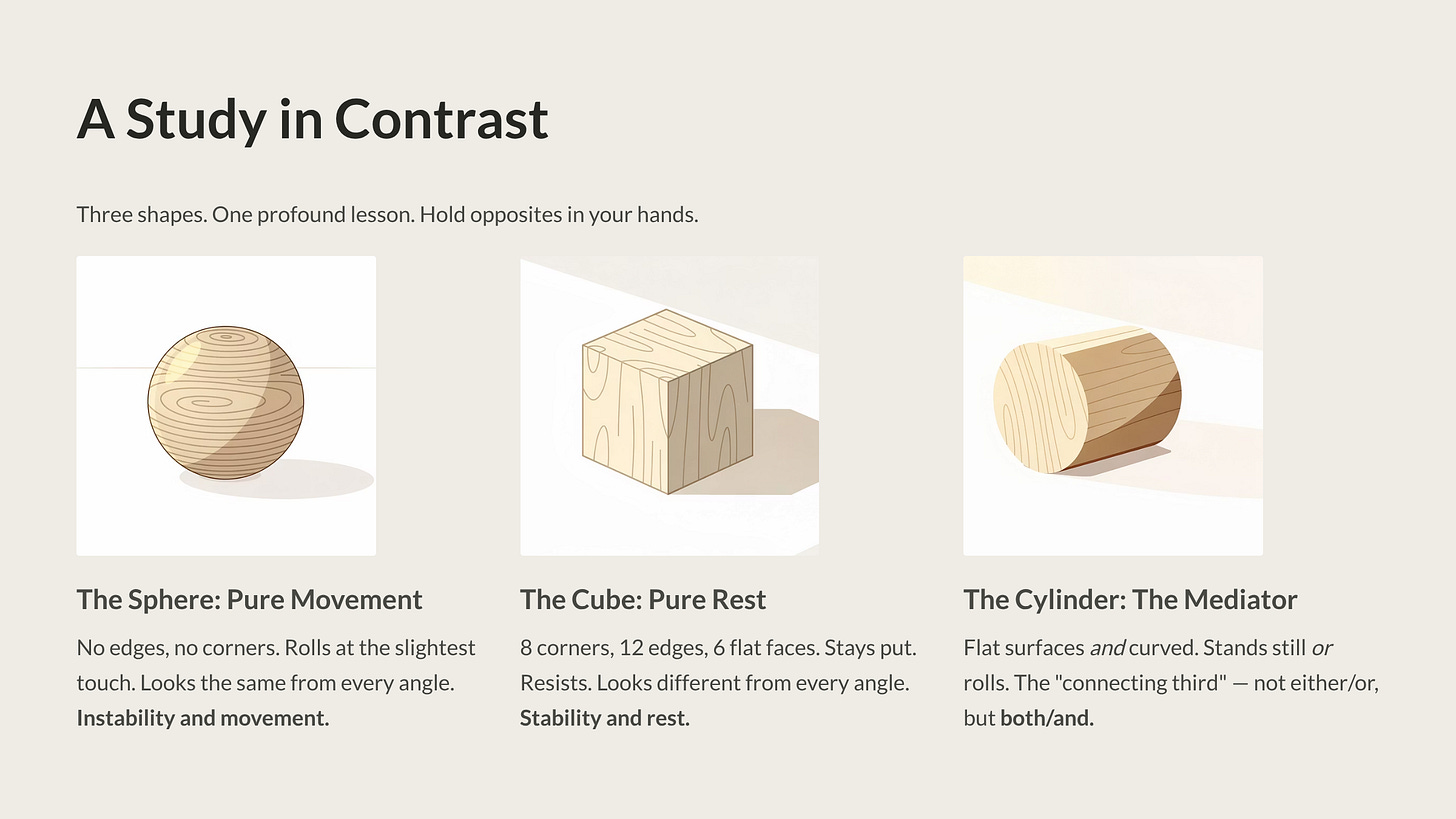

A Study in Contrast: The Law of Opposites in Your Hands

If you’ve been following our series, you’ll remember Fröbel’s “Law of Opposites”—his belief that children understand the world by encountering contrasts. Light makes sense because of dark. Soft makes sense because of hard. Movement makes sense because of stillness.

The Second Gift is the Law of Opposites made physical. You can hold it. You can roll it. You can stack it. And your child can feel the difference between two extremes of existence.

The Sphere: Pure Movement

Pick up the wooden sphere. Run your fingers over it. There are no edges, no corners, no flat surfaces. It’s smooth in every direction—what Fröbel called “all-sided.”

Set it on a table and it won’t stay put. Even the tiniest impulse sends it rolling. And no matter how it turns—no matter which angle you view it from—it always looks exactly the same.

The sphere represents instability and movement. It’s restless. Dynamic. Always ready to go somewhere.

Your child already knows this intuitively from the First Gift. The ball rolls. The ball bounces. The ball never sits still. The wooden sphere of the Second Gift confirms and extends that understanding into solid form.

The Cube: Pure Rest

Now pick up the cube. Feel the flat faces. Count the sharp corners—eight of them. Run your finger along the twelve edges. This is a shape with what Fröbel called “particular-sidedness.” Every face is distinct. Every angle is defined.

Set it on the table. It stays. Push it gently. It resists. Tip it on its edge and it falls flat again, settling firmly onto one of its six faces.

The cube represents stability and rest. It’s grounded. Dependable. It doesn’t roll, doesn’t wander, doesn’t change its appearance when you turn it. Each face looks different from the next.

Here’s the contrast that matters: the sphere has no preferred position. The cube has six. The sphere looks the same from every angle. The cube looks different from every angle. The sphere moves at the slightest touch. The cube holds its ground.

Same wood. Same size. Opposite behaviour. And your child, holding one in each hand, can feel that difference in their bones.

The Cylinder: The Mediator

This is where Fröbel’s thinking gets elegant.

He believed that every pair of opposites needs a “connecting third”—something that bridges the gap between extremes and brings them into harmony.

Enter the cylinder.

Look at it closely with your child. It has flat surfaces—like the cube. It has a curved surface—like the sphere. It can stand upright and stay perfectly still—like the cube.

Lay it on its side and give it a nudge—it rolls, like the sphere.

The cylinder is both and neither. It’s the peacemaker between movement and rest, between curved and flat, between stability and instability. And for your child, this is a revelation: seemingly contradictory traits can exist within a single object.

This is more than geometry. This is a way of thinking. The world isn’t always “either/or.” Sometimes it’s “both/and.” The cylinder teaches that lesson before your child can spell any of those words.

Reality vs. Appearance: The Spinning Experiment

Here’s where the Second Gift becomes genuinely magical for children. And I mean the kind of magic that makes a five-year-old gasp.

Take the cube. Suspend it from a thread through its centre, or mount it on a thin stick. Now spin it. Fast.

Watch what happens.

The edges blur. The corners vanish. And the cube—that solid, angular, stubbornly still cube—appears to transform into a cylinder. Spin it from a corner instead, and it looks like a double cone.

Now stop the spin. The cube is back. Edges. Corners. Flat faces. Nothing has changed.

Your child just learned one of the most important lessons in all of education: the way things appear to our senses isn’t always the full story.

The cube looked like it changed. But its essence—its corners, edges, and faces—remained exactly the same. The appearance shifted. The reality didn’t.

Fröbel designed this exercise deliberately. He wanted children to understand the difference between what something seems to be and what it actually is. That distinction is the foundation of:

- Scientific thinking: Appearances can deceive. We need to investigate, measure, and test before drawing conclusions.

- Critical thinking: Just because something looks a certain way doesn’t mean it is that way. Question what you see.

- Mathematical reasoning: Shapes have properties that remain constant regardless of perspective or motion. A cube rotated is still a cube.

And your child arrives at all of this not through a lecture, but through spinning a wooden block on a string and watching with wide eyes.

Bringing the Second Gift Into Your Homeschool

Here’s how to use the Second Gift intentionally at different ages, whether you have a Spielgaben set or are working with wooden shapes you already own.

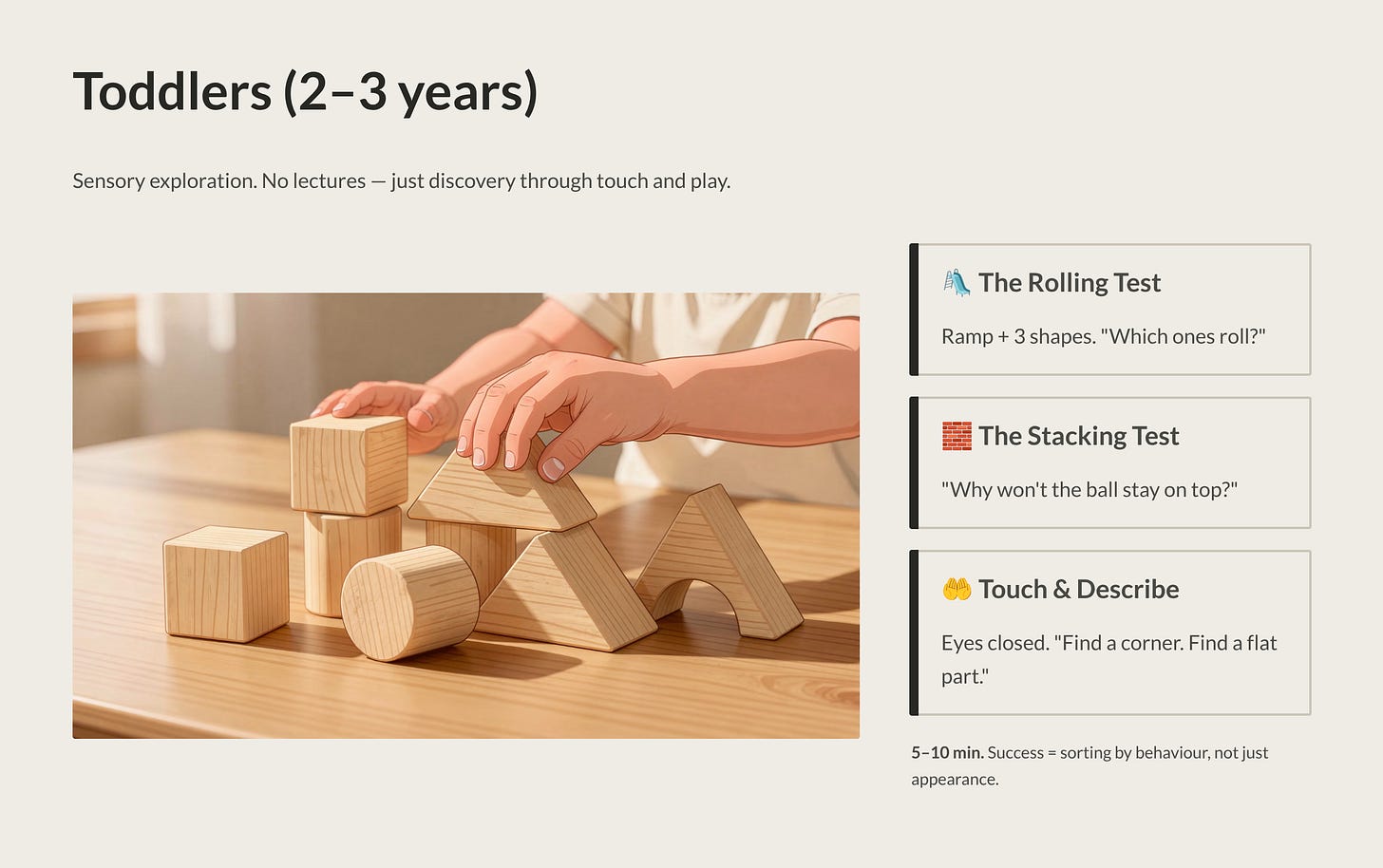

For Toddlers (2–3 years)

At this age, the focus is on sensory exploration and basic comparison. Don’t worry about naming properties—let your child discover them through touch and play.

Materials: A wooden sphere, cylinder, and cube of similar size. The Spielgaben Second Gift provides these in natural wood with a hanging frame, but you can start with any solid wooden shapes from a craft store or building set.

Activities:

- The rolling test. Place all three shapes at the top of a gentle ramp (a cutting board propped on a book works perfectly). Let your child release each one. “Which ones roll? Which one doesn’t?” No need to explain why—the observation itself is the lesson.

- The stacking test. Ask your child to stack the shapes. The cube stacks easily. The cylinder can stand upright. The sphere? It won’t cooperate. “Why won’t the ball stay on top?” Let them puzzle over it.

- Touch and describe. Have your child close their eyes and hand them each shape. “Does it feel smooth all over? Can you find a corner? Can you find a flat part?” This builds tactile discrimination and descriptive vocabulary.

Time commitment: 5–10 minutes. Follow their curiosity.

What success looks like: Your child begins sorting the shapes by behaviour (”these roll, this doesn’t”) rather than just by appearance. They start predicting which shape will roll before testing it.

For Preschoolers (3–5 years)

Now we introduce comparison, language, and the beginnings of the spinning experiment.

Activities:

- Opposite hunt. Hold up the sphere and the cube. Ask your child to tell you everything that’s different about them. Write or draw their observations. Then hold up the cylinder and ask: “Is this one more like the ball or more like the box?” Watch them wrestle with “both”—that’s exactly the point.

- The spinning reveal. Suspend the cube from a string and spin it. “What does it look like now? Has it really changed?” Stop the spin. “Look—it’s still a cube!” This never gets old for preschoolers. They’ll want to do it dozens of times, and every repetition deepens the lesson.

- Shape hunt in the house. “Can you find something shaped like a sphere? A cylinder? A cube?” Oranges, tin cans, tissue boxes—the world is full of these three forms. This connects the Gift to real life, just as Fröbel intended.

- Imprint exploration. Dip each shape in paint and press it onto paper. The cube leaves a square. The cylinder leaves a rectangle or circle depending on how it’s pressed. The sphere leaves a circle. “Why does the same shape make different prints?” This introduces the idea that three-dimensional objects create two-dimensional images—a concept that will matter enormously in maths later.

Time commitment: 15–20 minutes per session.

What success looks like: Your child uses comparison language spontaneously (”this one’s like the cube because…”). They predict what the spinning cube will look like before you spin it. They identify sphere, cylinder, and cube forms in everyday objects without being prompted.

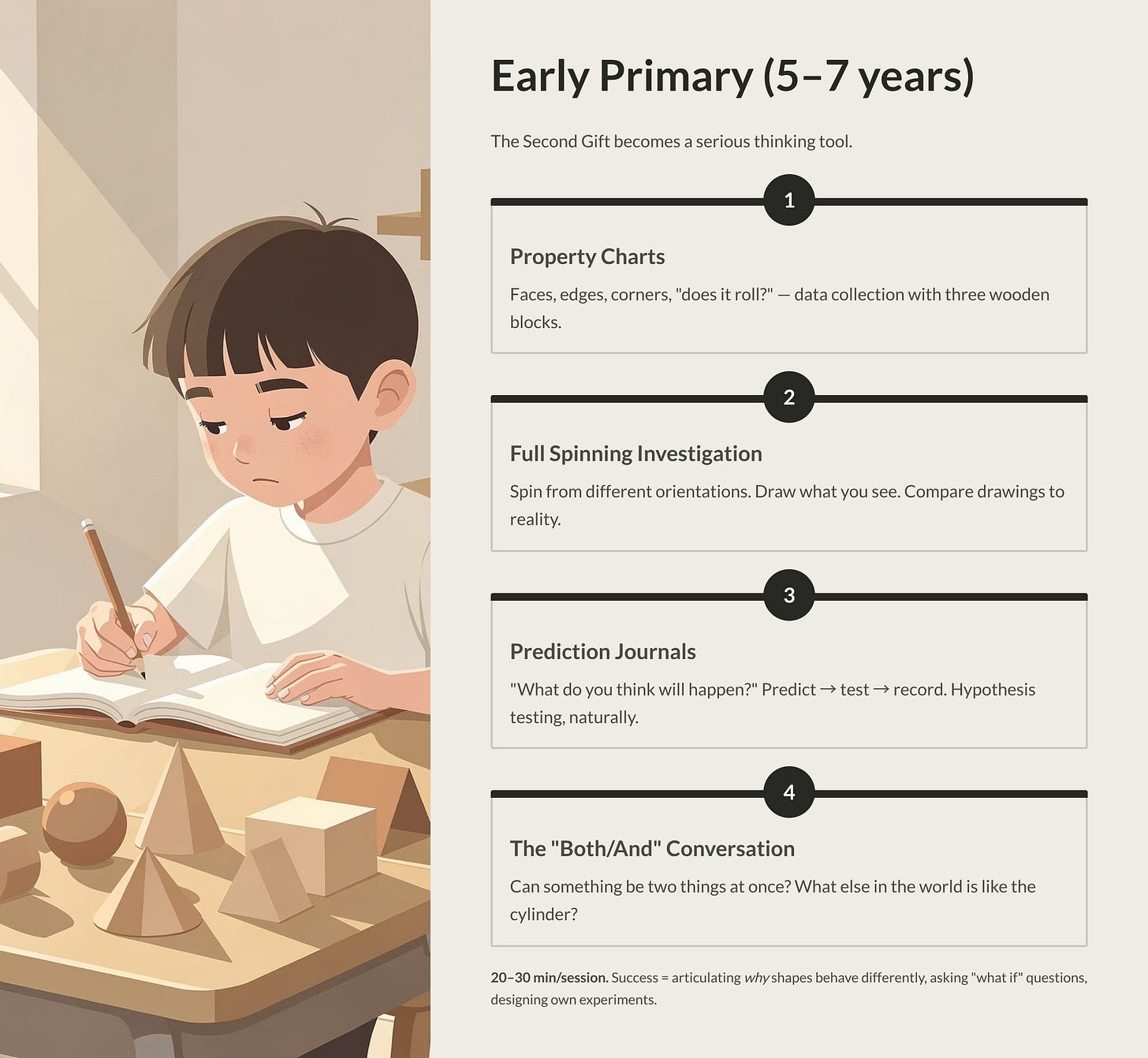

For Early Primary (5–7 years)

This is where the Second Gift becomes a serious thinking tool.

Activities:

- Property charts. Create a simple chart with your child: shape name, number of faces, number of edges, number of corners, “does it roll?”, “does it stack?” Fill it in together through observation. This is data collection and classification—core scientific skills—using three wooden blocks.

- The full spinning investigation. Spin each shape from different orientations. The cube from its face. The cube from its corner. The cylinder from its flat end. The cylinder from its curved side. Ask your child to draw what each one looks like while spinning. Compare the drawings to the actual shapes. “Which drawings look the same? Which look different? Why?”

- Prediction journals. Before each experiment, ask: “What do you think will happen?” Write the prediction. Test it. Write what actually happened. “Were you right? What surprised you?” This formalises hypothesis testing in a way that’s natural and engaging.

- The “both/and” conversation. Use the cylinder as a springboard for deeper thinking: “Can something be two things at once? Can something be still AND able to move? Can you think of other things in the world that are like the cylinder—a bit of this and a bit of that?” This builds abstract thinking and nuance.

Time commitment: 20–30 minutes per session.

What success looks like: Your child articulates why shapes behave differently, not just that they do. They connect the spinning illusion to the broader idea that appearances can be misleading. They ask “what if” questions and design their own shape experiments. They begin using the vocabulary of properties (faces, edges, corners) naturally.

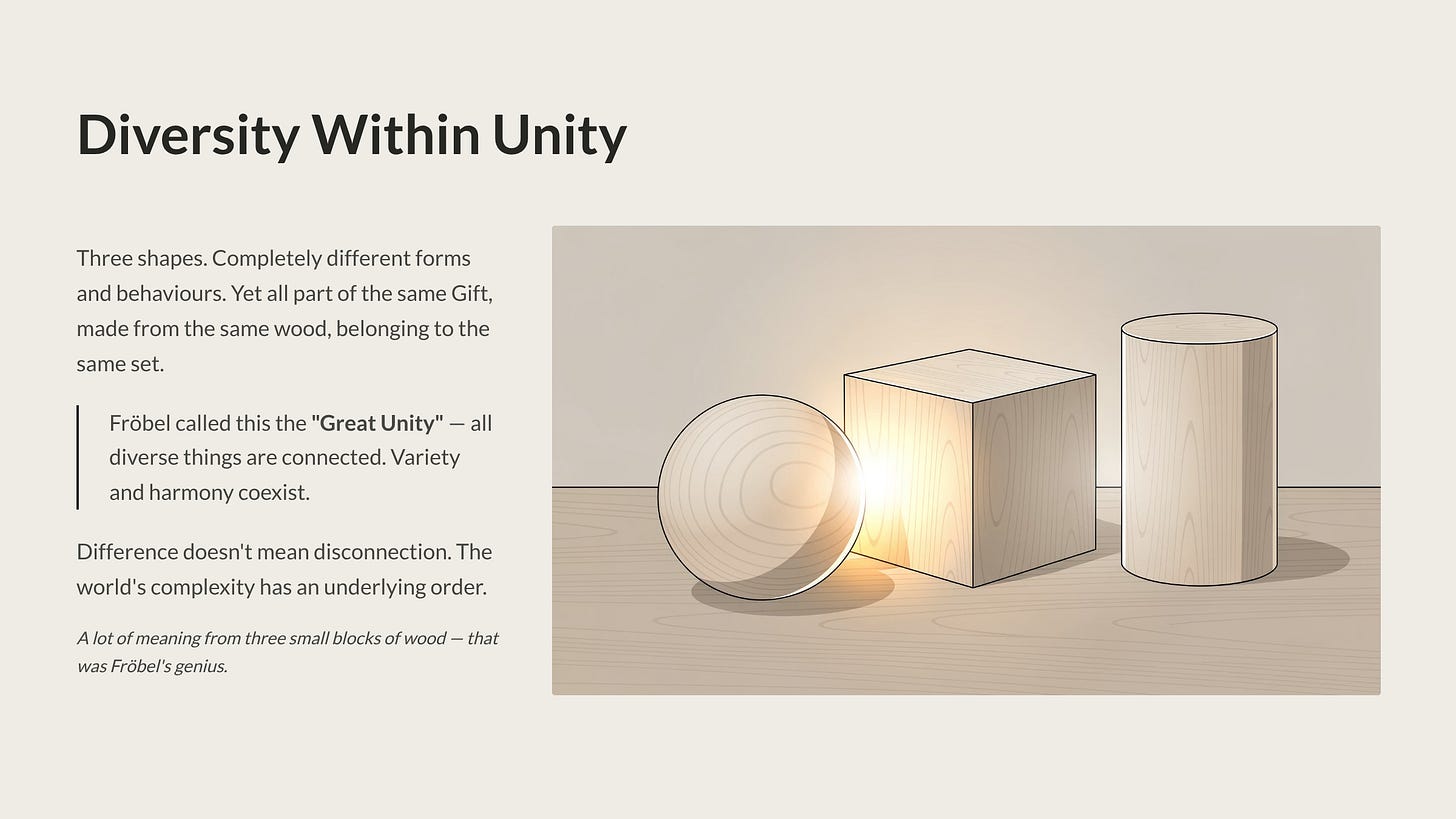

The Deeper Lesson: Diversity Within Unity

There’s one more thing Fröbel wanted children to take from the Second Gift, and it goes beyond geometry.

He intended for these experiences to show that diversity is not fragmentation. The sphere, cylinder, and cube look completely different. They behave in completely different ways. But they are all part of the same Gift, made from the same wood, belonging to the same set.

Different forms. One unity.

Fröbel called this the “Great Unity”—the idea that all diverse things in the world are connected, that variety and harmony coexist. For a young child, this begins as a physical experience with three wooden shapes. But the seed it plants grows into something much larger: an understanding that difference doesn’t mean disconnection, and that the world’s complexity has an underlying order.

That’s a lot of meaning from three small blocks of wood. But that was Fröbel’s genius—packing infinite lessons into the simplest possible forms, and trusting children to find them.

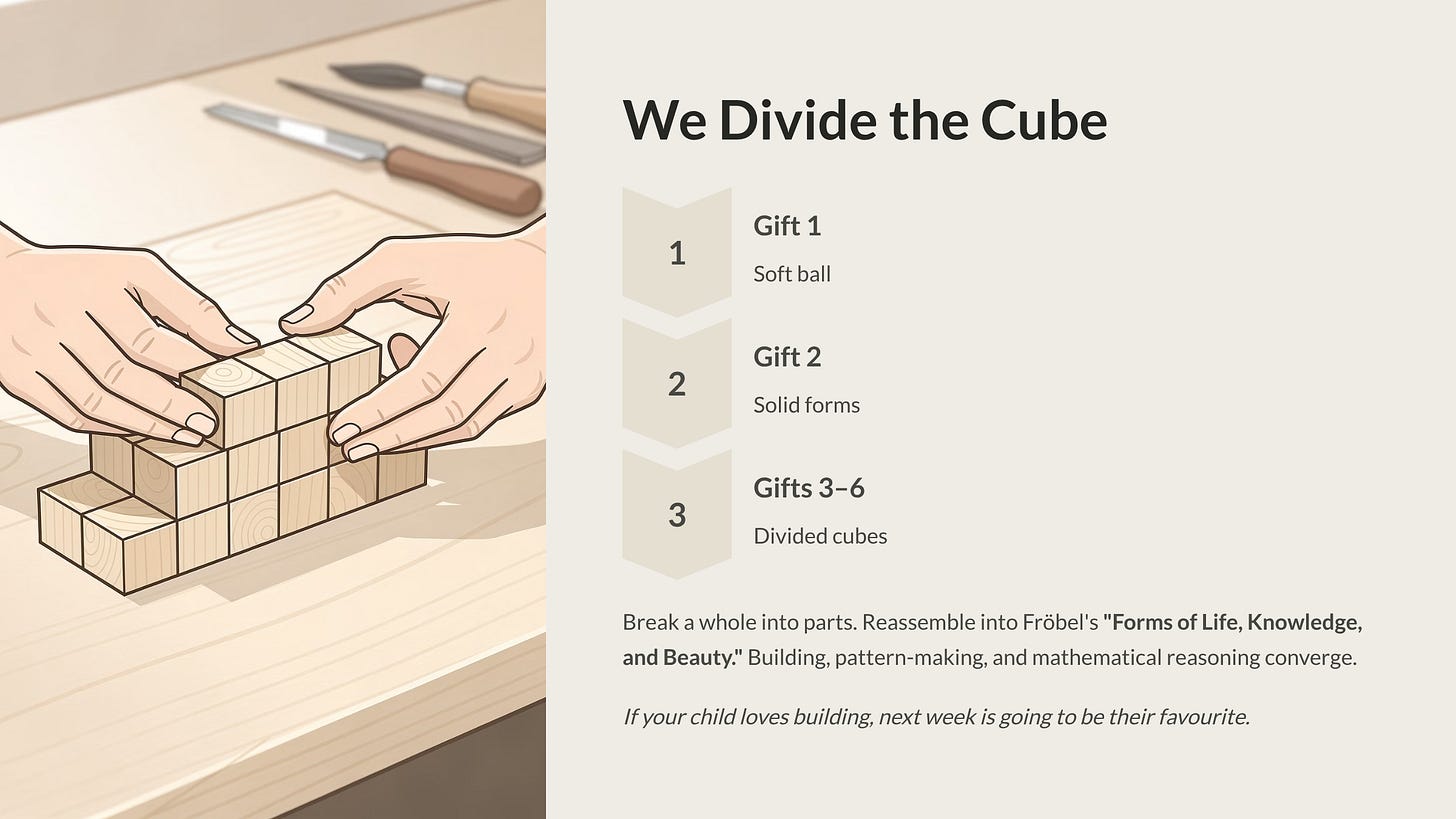

Coming Next Week

We’ve moved from the soft ball to solid forms. From a single shape to three contrasting ones. From pure movement to the tension between movement and rest.

Next week, we go further. We take the cube and divide it.

Gifts 3 through 6 introduce the magic of divided cubes—where children learn to break a whole into parts and reassemble those parts into what Fröbel called “Forms of Life, Knowledge, and Beauty.” It’s where building, pattern-making, and mathematical reasoning converge into one of the most powerful learning experiences Fröbel ever designed.

If your child loves building, next week’s post is going to be their favourite.

This is part of our ongoing Fröbel Gifts Masterclass at the Spielgaben Homeschool Series. If you’re new here, start with our earlier posts on Fröbel’s life story, the Law of Opposites, and Holistic Education: Head, Heart, and Hand and The First Gift: The Ball.

Subscribe here to follow the complete Masterclass series and give your child the gift of purposeful play.

LEAVE A COMMENT