Daily Routines for Manipulative Math That Actually Work (Not Just Look Good on Paper)

You bought the manipulatives. You read about the philosophy. You understand why hands-on math matters.

Now you’re staring at Monday morning, wondering: “What does this actually look like? How long do we spend? What’s my role? And how do I keep this from devolving into chaos?”

Here’s what nobody tells you when they recommend manipulative-based math: the curriculum is only half the challenge. The other half is building a sustainable daily routine that works with real children in your actual home.

I’ve watched parents invest in beautiful educational materials—Spielgaben sets, Cuisenaire rods, base-ten blocks, fraction circles—only to see them gather dust on the shelf within a month. Not because the materials don’t work. But because the daily implementation felt overwhelming, unstructured, or impossible to maintain.

The problem isn’t you. The problem is that most manipulative math resources explain what to teach but not how to structure your day around it.

Let me fix that right now.

Why Your Current Math Block Isn’t Working

Before we talk about what works, let’s diagnose why the typical approach fails.

The 45-minute math block fantasy:

You sit down with your child at 9am. You pull out the manipulatives. You introduce the concept. Your child explores. You guide. You ask questions. Understanding develops organically. At 9:45, you clean up, having covered exactly what you planned.

Beautiful. Impossible.

The 45-minute math block reality:

9:00 – Sit down. Child asks for a snack. 9:03 – Get snack. Sit down again. Can’t find the manipulatives you need. 9:07 – Find manipulatives. Younger sibling grabs half of them. 9:10 – Retrieve manipulatives. Older child has forgotten what you’re doing. 9:12 – Reintroduce concept. Child explores for 4 minutes productively. 9:16 – Child gets distracted. You redirect. 9:18 – Make real progress for 6 minutes. 9:24 – Child announces they need the bathroom. 9:28 – Resume. Momentum is gone. 9:35 – Give up. Nobody learned anything. Manipulatives everywhere.

You’re not failing. You’re fighting a structure that doesn’t match how young children actually learn.

Here’s what works instead.

The Three-Phase Approach (That Respects Reality)

Forget the single 45-minute block. That’s adult-brain thinking applied to child learning.

Young children learn math best in three short, distinct phases spread across the day. Each phase has a different purpose. Together, they create deeper understanding with less friction than any single marathon session.

Phase 1: Morning Exploration (10-15 minutes)

When: First thing after breakfast, before any formal academics

Purpose: Concrete manipulation and concept introduction

Your role: Minimal. You’re a facilitator, not a teacher.

This is when your child’s brain is fresh and their hands are ready to work. You set up the materials, introduce the concept or problem briefly, then step back.

What this looks like:

You’re working on addition with regrouping. You set out base-ten blocks on a tray: two ten-rods and eight unit cubes.

You say: “You have 28. Show me what happens when you add 7 more.”

Then you leave. Make your coffee. Tidy the kitchen. Check in after 5 minutes.

Your child experiments. Makes mistakes. Self-corrects. Discovers that adding 7 to 28 means you need to regroup the units into another ten-rod.

Key principles:

- Setup before your child arrives (materials organized, problem ready)

- Brief introduction only: “Here’s what we’re exploring today”

- No lecturing, no step-by-step instruction yet

- Allow genuine exploration and productive struggle

- Observe but don’t hover

Time commitment: 10-15 minutes of child engagement, 5 minutes of your setup beforehand

What success looks like: Your child engages with the materials, attempts the problem, and shows thinking—even if the initial approach is wrong. You’re building comfort with concrete manipulation.

Phase 2: Midday Discussion (5-10 minutes)

When: Late morning or after lunch, at least 90 minutes after Phase 1

Purpose: Language development and conceptual clarity

Your role: Active participant in mathematical conversation

Now you return to what your child explored earlier. You ask questions. You introduce vocabulary. You help them articulate what they discovered through manipulation.

What this looks like:

You sit together with the same manipulatives from the morning.

“Show me what you figured out about 28+7.”

Your child demonstrates. You ask: “Why did you need to make a new ten-rod?”

“Because I had more than ten units.”

“Exactly. We call that regrouping. When you have ten or more of something, you can regroup it into the next place value. Can you show me another problem where you’d need to regroup?”

Key principles:

- Reference the morning’s concrete work

- Ask questions more than you explain

- Introduce precise mathematical vocabulary naturally

- Have your child teach you: “Explain it like I don’t understand”

- Make connections to previous concepts

Time commitment: 5-10 minutes of focused conversation

What success looks like: Your child can explain the concept in their own words, uses the manipulatives to demonstrate understanding, and makes connections you didn’t explicitly state.

Phase 3: Evening Application (5-10 minutes)

When: Late afternoon or early evening

Purpose: Transfer to symbolic representation and real-world application

Your role: Guide the transition from concrete to abstract

Now your child works with the concept in a different form—drawings, written problems, or real-life applications. You’re building the bridge from manipulatives to abstract thinking.

What this looks like:

“Remember this morning when you added 28+7 with the blocks? Can you draw what you did?”

Your child draws two long rectangles (tens) and eight small squares (ones), then adds seven more squares, showing how ten of them become another long rectangle.

“Now write it as a number problem: 28+7=___”

Your child writes: 28+7=35

“Tomorrow, let’s see if you can solve 36+8 the same way.”

Key principles:

- Connect directly to the morning’s concrete work

- Move gradually toward symbolic representation

- Apply to real situations when possible (”If we have 28 crackers and Dad brings home 7 more…”)

- Keep it brief—you’re reinforcing, not re-teaching

- End with a preview of tomorrow’s work

Time commitment: 5-10 minutes

What success looks like: Your child can represent the concrete work symbolically (in drawings or numbers), explains the connection between the manipulatives and the written problem, and feels confident about tomorrow’s challenge.

Why This Three-Phase Approach Actually Works

This structure aligns with how children’s brains process and retain information.

Spaced repetition: Your child encounters the same concept three times in one day, with breaks between. This is vastly more effective than one long session.

Different cognitive modes: Morning exploration is hands-on and discovery-based. Midday discussion is verbal and conceptual. Evening application is abstract and synthetic. Each mode strengthens different neural pathways.

Natural energy rhythms: You’re working with your child’s attention span, not against it. Three 10-minute sessions are easier than one 30-minute battle.

Built-in assessment: By Phase 3, you know exactly whether your child understood the concept. No quiz needed. If they can’t explain it or draw it, you stay on the same concept tomorrow.

Reduced parent fatigue: You’re not spending 45 minutes facilitating math. You’re spending 30 minutes total, spread across the day, with most of it being your child’s independent work.

The Weekly Rhythm That Prevents Overwhelm

Daily structure is only half the picture. You also need a weekly rhythm that allows concepts to deepen without feeling repetitive.

Here’s the framework I use and recommend:

Monday & Tuesday: New concept introduction

Use the three-phase approach to introduce a new concept or variation. Expect messiness. Expect confusion. That’s normal. Your job is exposure, not mastery.

Example: If you’re teaching area, Monday and Tuesday focus on “What is area? How do we measure space inside a shape?”

Wednesday & Thursday: Exploration and variation

Same concept, different context or manipulatives. Wednesday might be area with square tiles. Thursday might be area with graph paper. The mathematical idea is constant; the representation changes.

This is where understanding deepens. This is where transfer happens.

Friday: Application and assessment

Lighter, more playful. Apply the concept to a real problem. Use it in a game. Have your child teach it to a younger sibling. Assess informally whether you’re ready to move forward or need another week.

Example: Calculate the area of your child’s bedroom floor. How many square feet? How do we know? What if we used square inches instead?

Weekend: Mathematical play (optional)

No formal instruction. But leave the manipulatives accessible. Read a math-related picture book. Play a strategy game. Notice mathematical thinking in daily life.

Many parents report that their best “aha moments” happen on Saturday morning when their child spontaneously returns to the manipulatives from the week.

Material Organization That Saves Your Sanity

You can have the perfect routine and still fail if your materials are chaotic.

Here’s the organization system that works:

Organize by concept, not by type

Don’t keep all your blocks in one bin, all your tiles in another. You’ll waste 15 minutes searching every morning.

Instead, create concept-based trays or boxes:

- Addition/subtraction tray: Small manipulatives for counting and combining (buttons, Spielgaben’s counting pieces, colored cubes)

- Place value tray: Base-ten blocks, bundled craft sticks, place value cards

- Multiplication/division tray: Arrays materials (square tiles, graph paper, counters)

- Fraction tray: Fraction circles, pattern blocks, fraction strips

- Measurement tray: Rulers, measuring cups, string, unit cubes

The night-before rule

Every evening, set up tomorrow’s morning exploration. Five minutes of preparation prevents morning chaos.

Pull the tray you need. Set it on the table. Place a note card with the problem or prompt. Done.

When your child arrives at the table after breakfast, everything is ready. No delays. No excuses.

The cleanup protocol

This matters more than you think. Manipulative chaos kills momentum faster than anything.

Your rule: “Manipulatives return to their tray before we move to the next activity.”

Not “clean your room.” Not “put away all the toys.” Just: return the math materials to their designated spot.

This takes 2 minutes. It’s non-negotiable. It’s what makes tomorrow morning possible.

Teaching Multiple Ages Simultaneously (Without Losing Your Mind)

If you have children at different levels, the three-phase approach becomes even more valuable.

Strategy 1: Stagger Phase 1

Older child explores at 8:30. Younger child explores at 9:00. You’ve set up both trays the night before. Each child gets 10-15 minutes of individual exploration while the other is occupied elsewhere (breakfast, independent reading, play).

Strategy 2: Shared Phase 2

The midday discussion can often include both children, especially if they’re working on related concepts.

Eight-year-old is learning multiplication. Six-year-old is learning skip counting. You can have a conversation about both: “Show me how you counted by fives, Sophie. Now Sam, show me how 3×5 is related to what Sophie just did.”

Different manipulatives, different complexity, same underlying pattern.

Strategy 3: Phase 3 back-to-back

Evening application happens sequentially. Older child first (takes 5-7 minutes), then younger child (takes 5-7 minutes). Total time: 15 minutes for two children.

The secret: You’re not teaching two separate math lessons. You’re facilitating two different explorations of mathematical thinking within the same daily structure.

What Your Role Actually Is (And Isn’t)

The biggest mistake parents make with manipulative math is thinking they need to teach every moment.

You don’t.

Phase 1 – You are: The Preparer

You set up. You introduce briefly. You disappear.

You are not: hovering, correcting, explaining, directing.

Phase 2 – You are: The Questioner

You ask. You listen. You introduce vocabulary. You make connections.

You are not: lecturing, showing the “right way,” rushing to correct errors.

Phase 3 – You are: The Bridge-Builder

You help your child see the connection between concrete and abstract. You guide the representation.

You are not: completing the work for them, accepting “I don’t know” without gentle probing.

Across all phases – You are: The Observer

You’re watching for the five mastery markers we discussed last week. You’re noting what clicked and what confused. You’re deciding whether tomorrow continues this concept or moves forward.

You are not: performing. This isn’t about your teaching skills. It’s about your child’s thinking development.

Troubleshooting the Common Problems

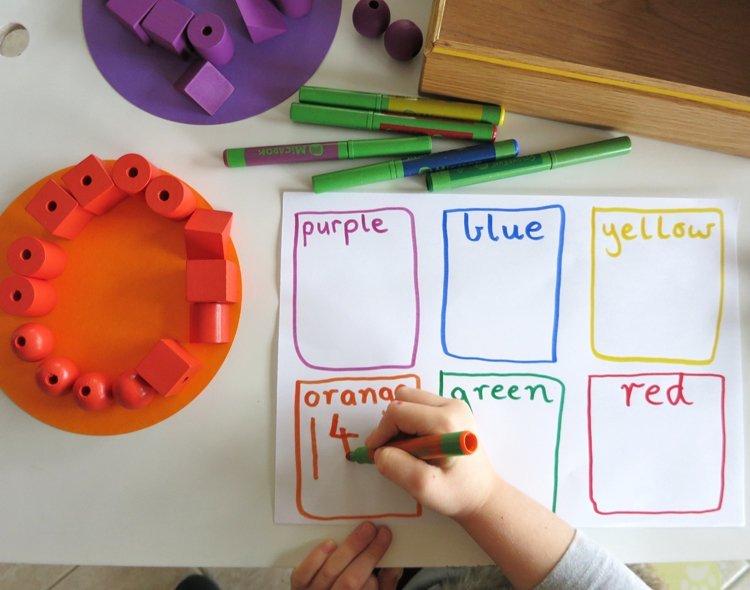

Problem 1: “My child just plays with the manipulatives instead of doing math”

Good. That’s Phase 1 working correctly.

Mathematical play is mathematical thinking. Your five-year-old building towers with unit cubes is exploring volume, stability, and counting. Your seven-year-old making patterns with Spielgaben tiles is working with symmetry and geometric relationships.

As long as your child is engaged with the materials, thinking is happening. You’ll bring focus during Phase 2.

If random play continues for weeks with no progression, you’re probably introducing concepts that are too advanced. Back up. Start with open exploration, then gradually add structure.

Problem 2: “We never get through all three phases in one day”

Then don’t.

Some days, you do Phases 1 and 2. Some days, just Phase 1. Some days, nothing at all because someone is sick or you have appointments.

The three-phase structure is a goal, not a rule. What matters is that when you do math, you’re building understanding through concrete exploration first, language second, and abstraction third.

Do those three things over two days if needed. Or three. The sequence matters more than the timeline.

Problem 3: “My child resists returning to the same concept multiple days in a row”

Change the representation. Same concept, different materials.

Monday: Addition with regrouping using base-ten blocks Tuesday: Addition with regrouping using money (dimes and pennies) Wednesday: Addition with regrouping by drawing on graph paper Thursday: Addition with regrouping with a word problem and whatever manipulative your child chooses

It’s the same mathematics. It feels like variety to your child.

Problem 4: “I don’t know enough math to answer my child’s questions”

Perfect. Say: “I don’t know. Let’s figure it out together.”

Then explore with manipulatives. Model mathematical curiosity. Show your child that not knowing is the beginning of learning, not the end.

You don’t need a math degree. You need manipulatives and questions: “What if…?” “Can you show me…?” “What do you notice…?”

Problem 5: “This feels like we’re going so slowly”

You’re not going slowly. You’re going deeply.

A child who spends three weeks genuinely understanding addition with regrouping will spend three days on subtraction with regrouping. A child who rushes through both in one week will struggle with both for months.

You’re not behind. You’re building foundations that accelerate everything that comes after.

Sample Week: Addition with Regrouping (Age 7-8)

Let me show you what this looks like in practice.

Monday

Phase 1 (8:45am, 12 minutes): Child has base-ten blocks arranged as 2 rods + 7 units (27). Note card says: “Add 6 more. What happens?” Child explores independently.

Phase 2 (11:30am, 8 minutes): You return together. “Show me what you discovered.” Child demonstrates that adding 6 units creates 13 units total, which becomes 1 rod + 3 units. You introduce vocabulary: “We call that regrouping—when you have enough units to make a new rod.”

Phase 3 (4:00pm, 7 minutes): “Draw what you did this morning.” Child draws the process. You write together: 27+6=33. “Tomorrow, try this: 35+8.”

Tuesday

Phase 1 (8:45am, 10 minutes): Child has 3 rods + 5 units (35). Challenge: “Add 8 more.” Child works independently, applies yesterday’s discovery about regrouping.

Phase 2 (11:30am, 6 minutes): “Was today easier than yesterday?” Child explains the process more confidently. You ask: “When do you know you need to regroup?” Child articulates the rule: “When I have 10 or more units.”

Phase 3 (4:00pm, 6 minutes): Child draws and writes 35+8=43. You present three problems on paper: 46+7, 28+5, 54+9. “Which ones will need regrouping? How do you know?” Child predicts correctly: first and third need regrouping because adding 7 to 6 units and 9 to 4 units both go over 10.

Wednesday

Phase 1 (9:00am, 15 minutes): Switch materials. Use dimes and pennies. 4 dimes + 3 pennies (43 cents). “Add 8 more cents.” Same concept, different representation. Child discovers that 10 pennies = 1 dime, just like 10 units = 1 rod.

Phase 2 (12:00pm, 7 minutes): “How is money like base-ten blocks?” Child makes the connection: place value is place value, whether blocks or coins.

Phase 3 (4:15pm, 8 minutes): Real-world application: “If we have 37¢ and Dad gives us 5¢ more, how much do we have?” Child solves it mentally, explaining: “37+5… I can take 3 from the 5 to make 40, then add 2 more to get 42¢.”

Thursday

Phase 1 (8:45am, 12 minutes): Graph paper and colored pencils. “Show 28+6 by coloring squares.” Child colors 2 complete rows of 10 (rods) and 8 more squares (units), then adds 6 more squares. Discovers regrouping by completing the third row.

Phase 2 (11:15am, 6 minutes): “What’s the same about blocks, money, and graph paper for addition?” Child identifies: all use groups of 10. This is the conceptual breakthrough.

Phase 3 (4:00pm, 5 minutes): Written practice: 5 problems, some requiring regrouping, some not. Child completes them with confidence, choosing to draw quick sketches on two of them.

Friday

Phase 1 (9:00am, 10 minutes): Game time. You say random addition problems. Child chooses whether to use manipulatives, draw, or solve mentally. “48+7” “55” “How did you know?” “I made 50, then added 5 more.”

Phase 2 (11:30am, 5 minutes): “What did you learn this week about addition?” Child explains regrouping in their own words. You assess: ready to move forward.

Phase 3: Skip today. Mastery demonstrated.

Weekend: Leave base-ten blocks accessible. Child builds structures during free play, unconsciously reinforcing place value.

Adjusting for Younger and Older Children

For younger children (ages 5-7):

- Shorten Phase 1 to 8-10 minutes

- Make Phase 2 more playful and less formal

- Phase 3 might just be telling a story about what they did, not written work

- Expect the weekly rhythm to stretch: one concept might take 2-3 weeks

For older children (ages 9-12):

- Phase 1 can extend to 20 minutes with more complex problems

- Phase 2 includes more sophisticated mathematical language and connections

- Phase 3 includes written explanations: “Explain why this method works”

- The weekly rhythm might compress: some concepts take just 3-4 days

The constant across all ages: Concrete before abstract. Manipulation before explanation. Understanding before speed.

What Spielgaben Offers (And What You Can Use Instead)

If you’re using Spielgaben, you already have a comprehensive system designed specifically for this three-phase approach. The gifts progress systematically from concrete to abstract, and each set builds on previous understanding.

Spielgaben advantages for this routine:

- All materials organized by mathematical concept (Gifts 3-6 for early numeracy, Gifts 7-8 for patterns and fractions, Gift 9 for place value and advanced operations)

- Each gift contains enough variety that you can change representations within the same concept without buying separate materials

- The progression is built-in, reducing your planning time

- The materials transition from concrete (solid blocks) to representational (flat tiles) to abstract (lines and points) as your child’s thinking develops

But you absolutely don’t need Spielgaben to make this work.

Alternative materials by phase:

Early addition/subtraction (K-2):

- Collections: buttons, dried beans, small toys, craft pom-poms

- Store-bought: counting bears, linking cubes, any small identical objects

- Homemade: cut squares from cardboard, collect pebbles, use LEGO bricks

Place value (1-4):

- Store-bought: base-ten blocks (widely available)

- Homemade: bundle popsicle sticks with rubber bands (ones, bundles of 10, bundles of 100)

- Household: money (pennies, dimes, dollars)

Multiplication/division (2-5):

- Store-bought: square tiles, graph paper

- Household: arrange objects in arrays (crackers, coins, anything identical)

- Homemade: draw arrays, cut squares from cardboard

Fractions (3-6):

- Store-bought: fraction circles or bars

- Household: paper plates cut into equal parts, food (pizza, sandwiches)

- Homemade: color-coded paper strips folded into equal parts

The materials matter less than the routine. Consistent daily practice with simple objects beats sporadic sessions with premium manipulatives.

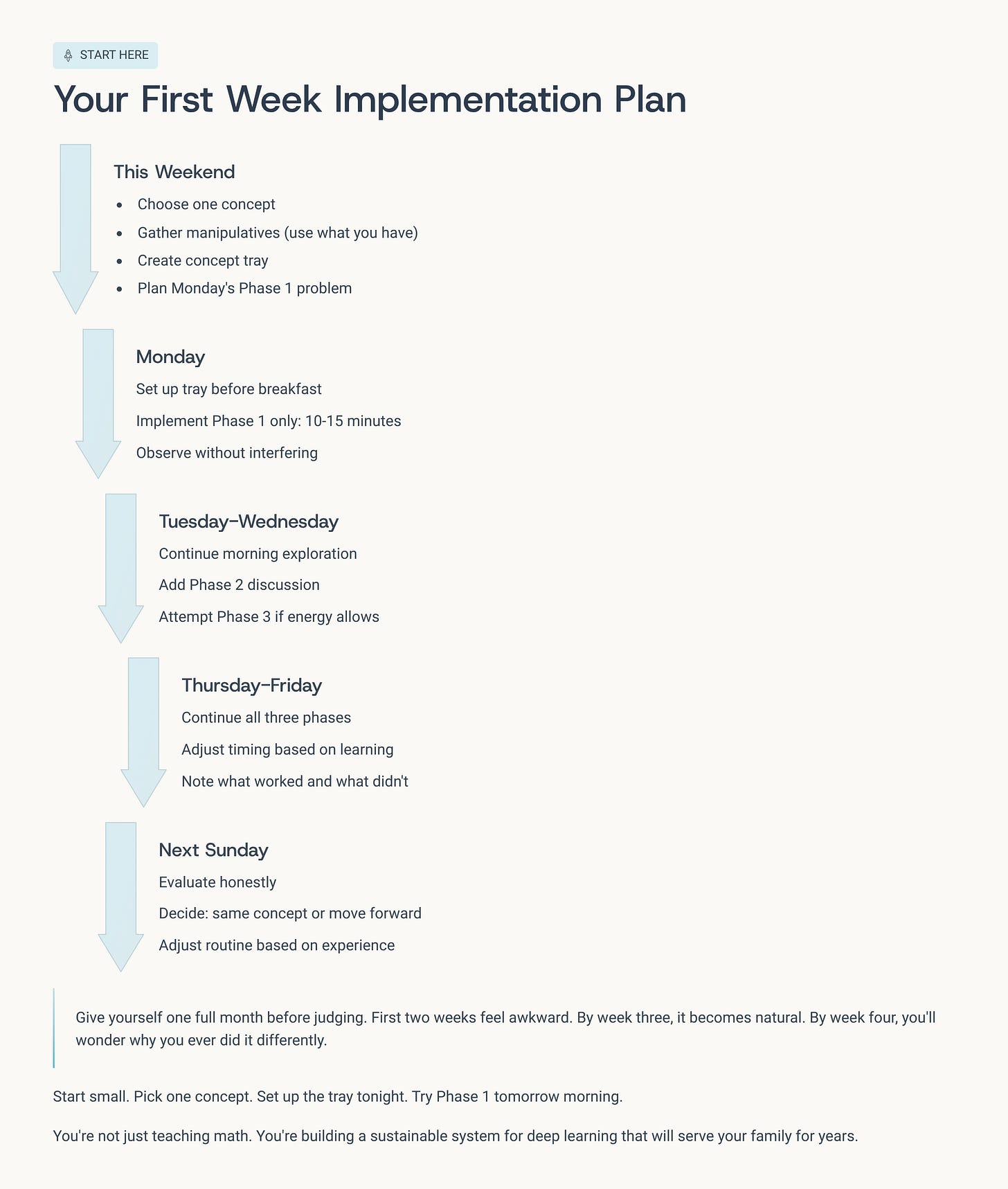

Your First Week Implementation Plan

Don’t try to implement everything at once. Start here:

This weekend:

- Choose one concept you’re currently teaching or about to teach

- Gather the manipulatives you’ll use (buy nothing new—use what you have)

- Create a concept tray with everything in one place

- Plan Monday’s Phase 1 exploration: one clear problem or prompt

Monday:

- Set up the tray before breakfast

- Implement Phase 1 only: 10-15 minutes of child exploration

- Observe what happens without interfering

- Don’t worry about Phases 2 or 3 yet

Tuesday:

- Set up morning exploration again

- Add Phase 2: 5-minute conversation about yesterday’s work

- Skip Phase 3 if you’re overwhelmed

Wednesday:

- Continue morning exploration (same concept, slightly different problem)

- Include Phase 2 discussion

- Attempt Phase 3 if energy allows: simple connection to abstract representation

Thursday & Friday:

- Continue all three phases

- Adjust timing based on what you learned earlier in the week

- Note what worked and what didn’t

Next Sunday:

- Evaluate the week honestly

- Decide: same concept next week (need more depth) or new concept (ready to progress)

- Adjust your routine based on what you learned

Give yourself one full month before judging whether this approach works for your family. The first two weeks will feel awkward. By week three, it becomes natural. By week four, you’ll wonder why you ever did it differently.

The Long View

A year from now, this structure won’t feel like a structure. It’ll feel like the natural rhythm of your homeschool.

Your child will automatically explore concepts with hands-on materials first. You’ll have daily mathematical conversations without thinking about it. The transition from concrete to abstract will happen organically.

And most importantly: your child will think mathematically, not just complete math pages.

That’s worth the adjustment period.

So start small. Pick one concept. Set up the tray tonight. Try Phase 1 tomorrow morning.

Build the routine one phase at a time, one week at a time.

You’re not just teaching math. You’re building a sustainable system for deep learning that will serve your family for years.

Whether you’re using Spielgaben’s systematic progression or gathering manipulatives from around your house, the three-phase daily structure remains the same. What matters isn’t the specific materials—it’s the routine that allows your child to encounter each concept first through manipulation, then through discussion, and finally through abstract representation. That’s how mathematical understanding develops. That’s what makes manipulative-based math sustainable in real homeschools.

LEAVE A COMMENT