How to Actually Use Your Manipulative Math Curriculum: Daily Routines That Work

You have the curriculum. You have the manipulatives. You might even have them organized in that nice container you bought specifically for this purpose.

Now you’re staring at “Week 1, Day 1” wondering: What does this actually look like when I’m sitting at the table with my 6-year-old who just asked for a snack for the third time?

This is the gap between curriculum and reality. And it’s where most homeschool math plans fall apart—not because the approach is wrong, but because the daily implementation feels awkward, chaotic, or impossibly time-consuming.

Here’s what actually works.

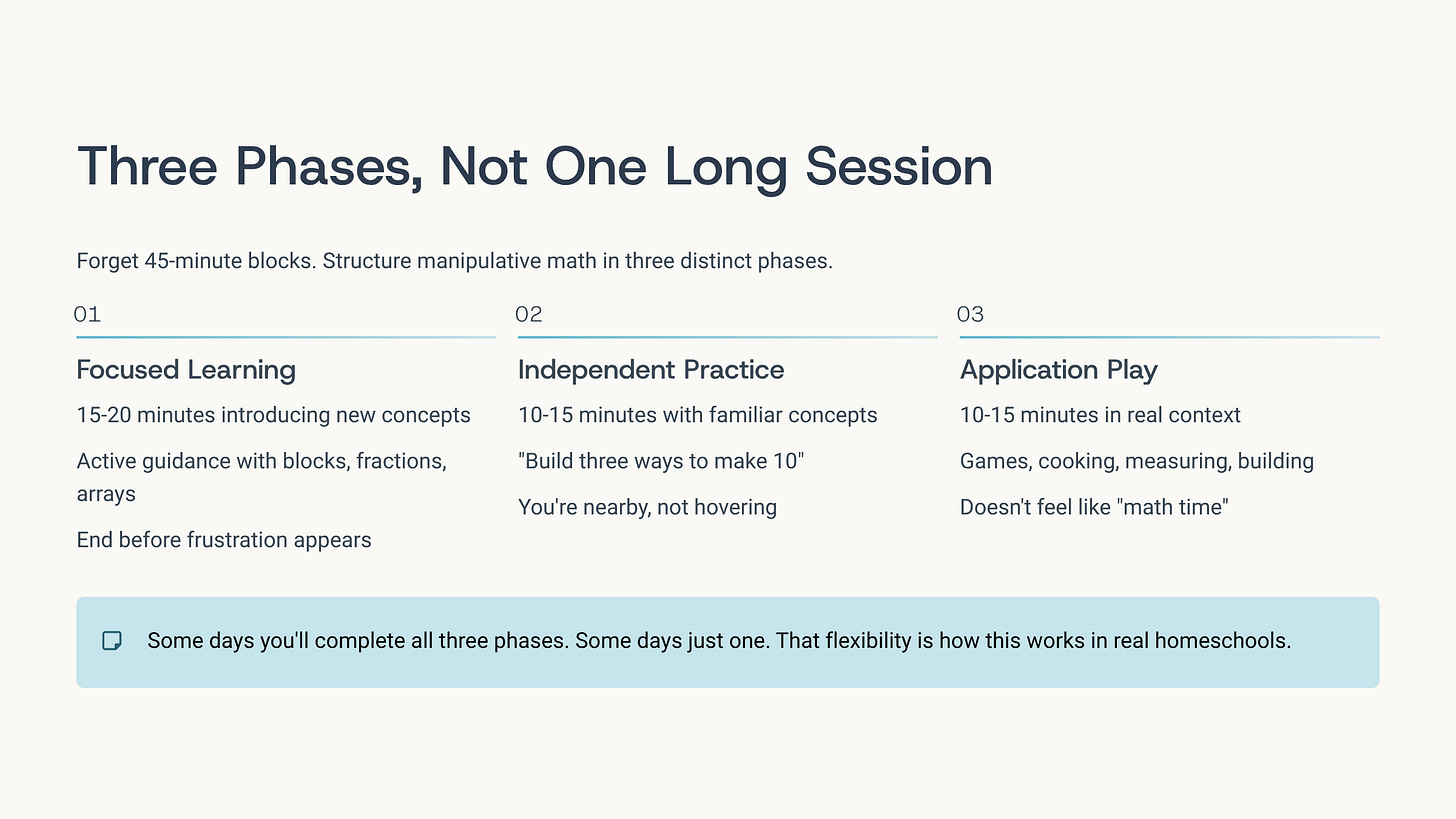

The Core Structure: Three Phases, Not One Long Session

Forget the idea of a continuous 45-minute math block where everyone sits perfectly engaged. That’s not how children learn with manipulatives, and it’s not how mathematical thinking develops.

Instead, structure your manipulative math time in three distinct phases. Each serves a different purpose. Each requires a different energy level from both you and your child.

Phase 1: Focused Learning (15-20 minutes) This is new concept time. You’re introducing something your child hasn’t encountered before, or deepening understanding of something recently introduced.

Your child is building with blocks, arranging fraction pieces, or creating arrays while you guide with questions. This requires their full attention and your active involvement.

End this phase before frustration appears. When you see the first signs of mental fatigue (fidgeting, distraction, rushed work), stop. You got what you needed.

Phase 2: Independent Practice (10-15 minutes) Now your child works with familiar concepts using manipulatives independently or with minimal guidance.

This isn’t worksheets. It’s: “Build three different ways to make 10 using red and blue blocks” or “Create as many arrays as you can that equal 12.”

You’re nearby but not hovering. You’re available for questions but not directing. This is where internalization happens.

Phase 3: Application Play (10-15 minutes) Mathematics appears in real context—games, cooking, measuring, building projects, or story problems with actual objects.

This phase often doesn’t feel like “math time” to your child. That’s the point. They’re applying mathematical thinking without the meta-cognitive awareness that they’re “doing math.”

Some days you’ll complete all three phases. Some days you’ll do Phase 1 and skip the rest. Some days you’ll skip Phase 1 entirely and do extended work in Phase 3.

That flexibility is how this actually works in real homeschools.

The Setup That Saves Time

Most manipulative math chaos comes from setup and cleanup, not the learning itself.

Before your math time starts:

Have today’s materials already out. Not in the storage container. Not on the shelf. On the table or workspace where you’ll use them.

If you’re working with base-ten blocks, you should see: the container of blocks, the place value mat, and perhaps number cards. Nothing else.

If you’re working with pattern blocks, you should see: pattern blocks in a tray, blank paper, and maybe the pattern block design cards you’re using today.

Your child shouldn’t help you hunt for materials. That’s five minutes of focus lost before you even begin.

Create a “math tray” for each concept area:

- Addition/Subtraction tray: counters in two colors, ten frames, number cards 0-20

- Place Value tray: base-ten blocks, place value mat, digit cards

- Multiplication tray: square tiles, graph paper, arrays template

- Fractions tray: fraction circles, fraction bars, fraction number line

When you’re working on multiplication, you grab the multiplication tray. Everything you need is there.

Spielgaben’s organization system does this naturally—each gift has its own box and specific purpose. But you can create the same system with plastic containers and labels from the dollar store.

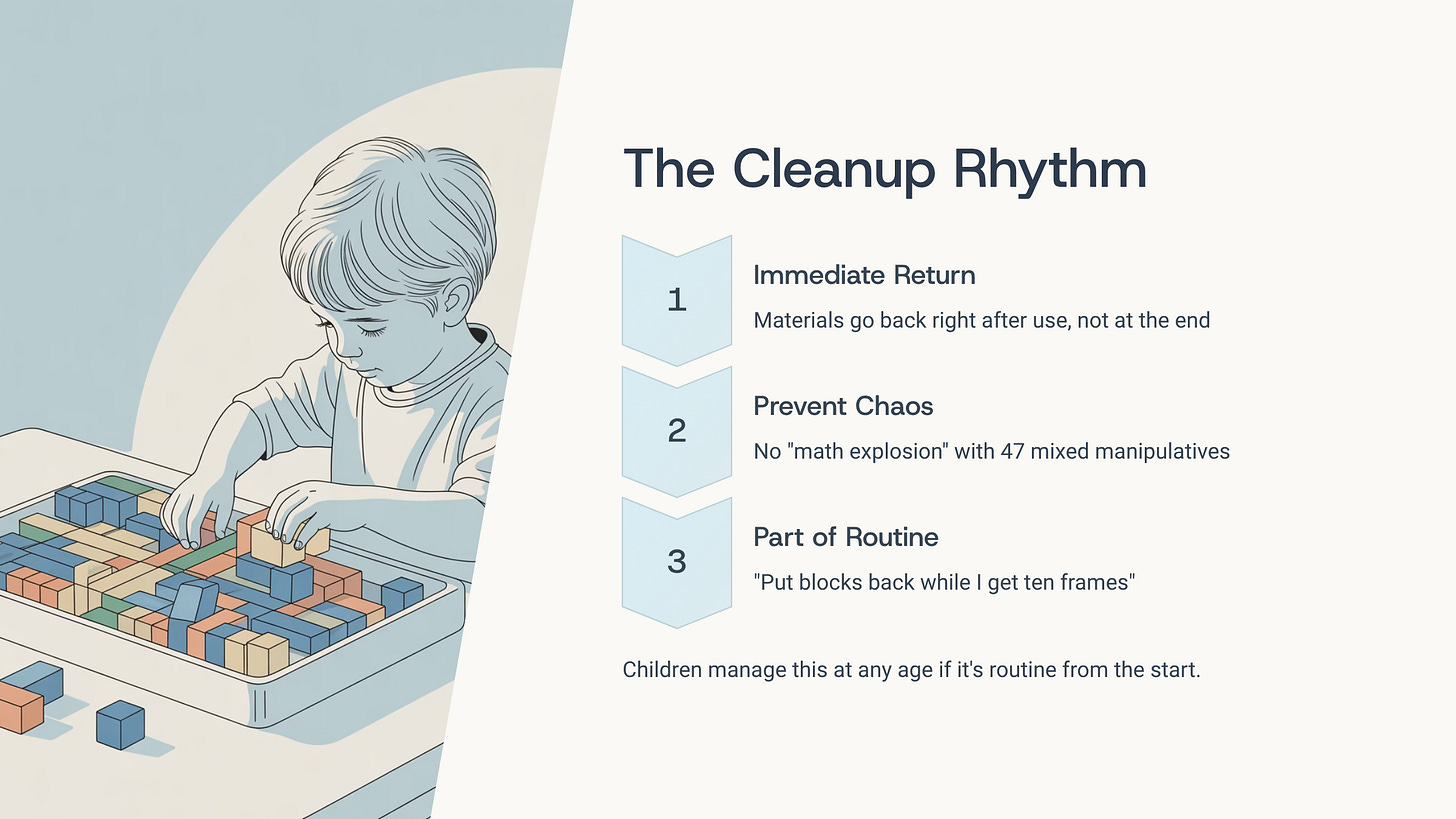

The cleanup rhythm:

Your child puts materials away immediately after use, not at the end of all three phases.

Finished with Phase 1 addition work? Counters go back in the container right now. Then you bring out Phase 2 materials.

This prevents the overwhelming “math explosion” on your table where 47 different manipulatives are mixed together and you spend 20 minutes sorting them back into containers.

Children can manage this cleanup at any age if you make it part of the routine from the start. “We’re done with the red and blue blocks now. Put them back in the container while I get the ten frames.”

What Your Role Actually Is

You’re not lecturing. You’re not showing your child how to do it and then having them replicate your method.

Your role is to:

1. Create the mathematical situation

“Here are 8 blocks. I wonder how many ways you can break them into two groups?”

“Can you build a rectangle that has 12 squares inside it?”

“Show me 37 using these base-ten blocks.”

You set up the challenge. Then you step back.

2. Ask questions that prompt thinking

Not: “Do you see how I did it? Now you do it.”

Instead:

- “What did you notice?”

- “Why did you choose that way?”

- “What would happen if…?”

- “Can you show me another way?”

- “How do you know you’re right?”

These questions aren’t quizzes. You’re genuinely curious about your child’s thinking. When they explain their reasoning, they solidify understanding.

3. Provide just-in-time support

When your child is stuck, you don’t solve the problem. You make the problem slightly more accessible.

Child struggling with 8+5?

- Don’t say: “8 needs 2 more to make 10, so take 2 from the 5…”

- Instead: “Let’s use the ten frame. Put the 8 in. Now what happens when you add the 5?”

Let the manipulative do the teaching. You’re just positioning them to see what it’s showing them.

4. Know when to wait

The most powerful teaching move in manipulative math is silence.

Your child is arranging blocks, thinking, trying something. Your impulse is to help, to guide, to speed things up.

Don’t.

Wait. Give them time to think. Mathematical reasoning needs space.

Count to ten in your head before you say anything. Most of the time, your child will work through the problem before you reach ten.

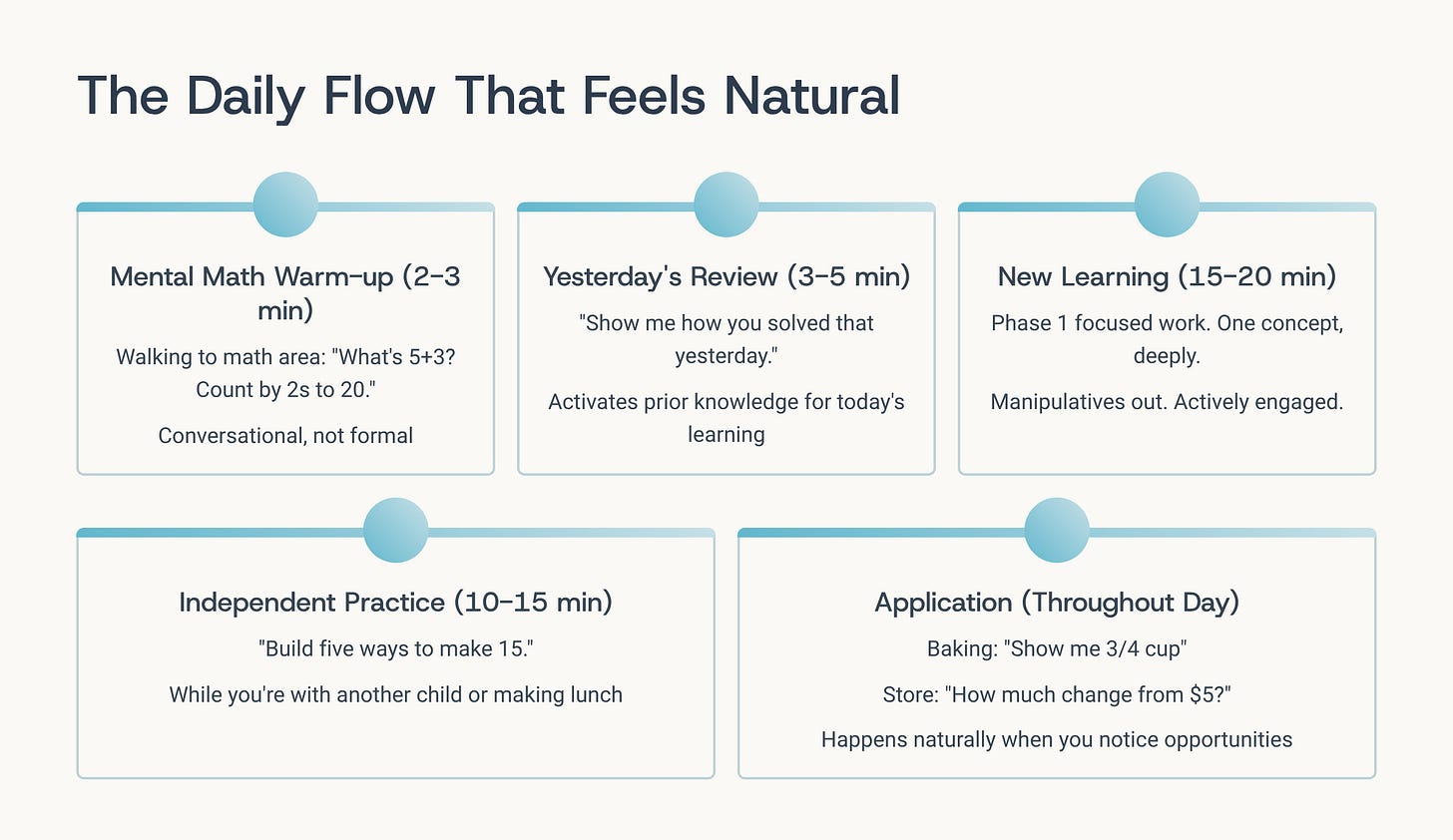

The Daily Flow That Feels Natural

Morning math time (for most families):

Math happens after breakfast, before the day gets chaotic. Brains are fresh. You have patience. Your child has energy.

But if your child is a slow morning starter, afternoon math works fine. Don’t fight your family’s natural rhythms because someone said “math should be in the morning.”

The actual daily sequence:

- Quick mental math warm-up (2-3 minutes): Not sitting at a table. While you’re walking to the math area, or setting out materials: “What’s 5+3? What’s one more than 9? Count by 2s to 20.”

This transitions their brain into mathematical thinking. It’s not formal—it’s conversational.

- Yesterday’s review (3-5 minutes): “Show me again how you solved that problem yesterday.”

This isn’t drilling. It’s activating prior knowledge so today’s new learning has something to connect to.

If your child struggles to remember or demonstrate yesterday’s concept, today isn’t the day for new material. Spend more time with yesterday’s concept instead.

- New learning or deepening (15-20 minutes): This is your Phase 1 focused work. Manipulatives are out. You’re actively engaged.

One concept. One exploration. Not “addition and then we’ll do some subtraction and also look at this pattern.”

One thing, deeply.

- Independent practice while you’re with another child or making lunch (10-15 minutes): “Build five different ways to make 15 using the blocks. I’ll be right here if you need me.”

Your kindergartener is doing this while you work with your third grader. Or while you’re chopping vegetables. Or while you’re nursing the baby.

This phase is designed to not require you. If your child needs constant help during independent practice, the concept isn’t ready for independence yet. Go back to Phase 1 work for a few more days.

- Application sometime during the day (naturally occurring): You’re baking. “We need 3/4 cup of flour. Show me 3/4 on this measuring cup.”

You’re at the store. “These crackers are $2.50. If I give the cashier $5, how much change will I get?”

You’re building with blocks. “Your tower is 12 blocks tall. My tower is 7 blocks. How many more blocks does yours have?”

This happens when it happens. You don’t schedule it. You notice mathematical opportunities and point them out.

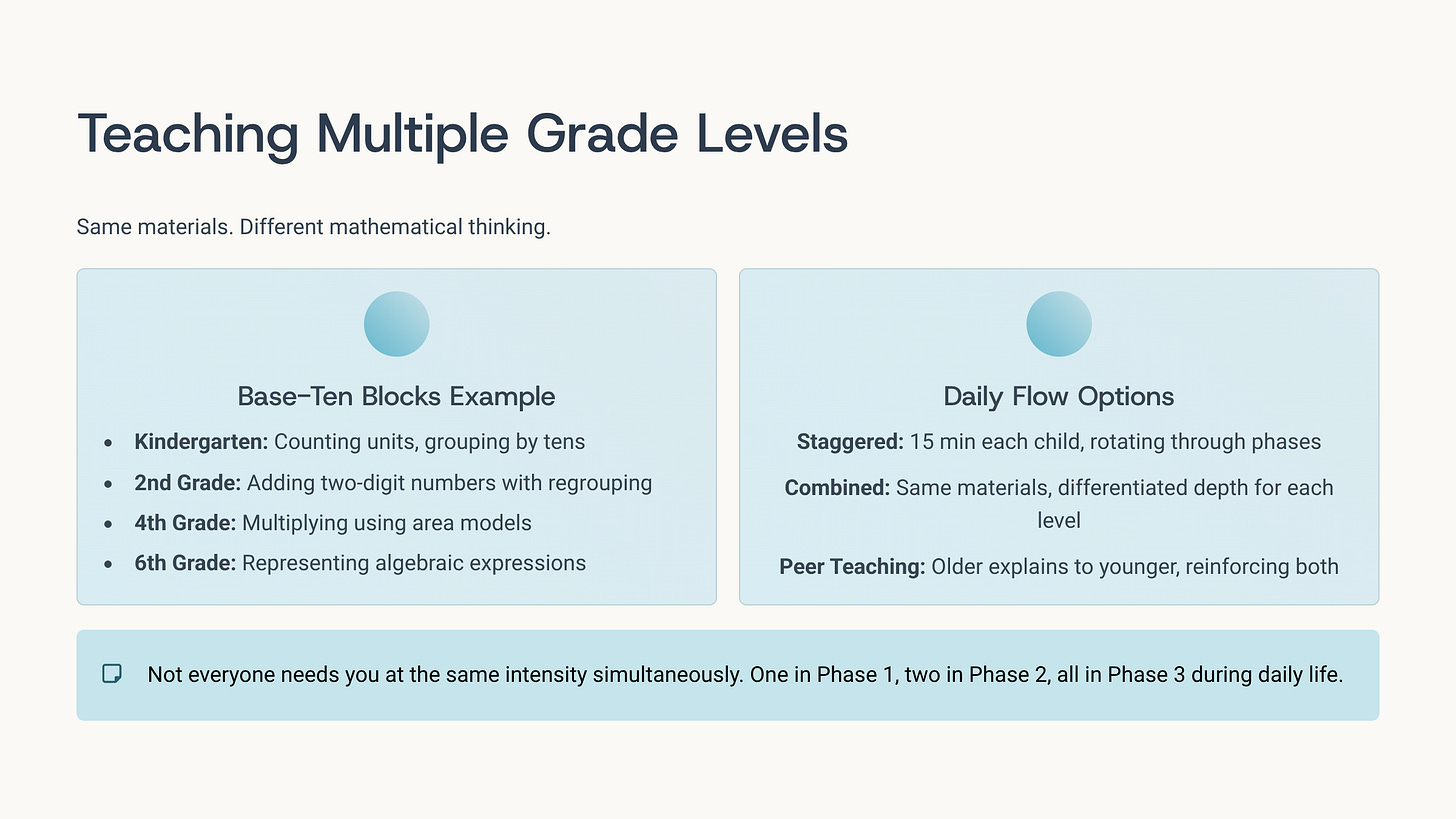

When You’re Teaching Multiple Grade Levels

The beautiful thing about manipulative math: different children can use the same materials for different mathematical thinking.

Example with base-ten blocks:

- Your kindergartener: Counting units one by one, grouping them by tens

- Your second grader: Adding two-digit numbers with regrouping

- Your fourth grader: Multiplying two-digit numbers using area models

- Your sixth grader: Representing algebraic expressions

Same blocks. Different mathematics.

Your daily flow with multiple children:

Option 1: Staggered individual time

- 8:30-8:45: Work with K on counting (Phase 1)

- 8:45-9:00: K does independent counting game (Phase 2) while you work with 2nd grader on addition (Phase 1)

- 9:00-9:15: 2nd grader practices independently while you work with 4th grader

- Throughout day: All children encounter Phase 3 application naturally

Option 2: Combined concept with differentiated depth

- Everyone works with pattern blocks today

- K: Creating and extending AB patterns

- 2nd grader: Creating growing patterns and complex repeating patterns

- 4th grader: Using pattern blocks to explore fractions and find equivalent fractions

- You rotate: 5 minutes with each child, giving specific guidance for their level

Option 3: Older teaches younger

- 4th grader explains place value to 2nd grader using base-ten blocks

- This reinforces 4th grader’s understanding while giving 2nd grader peer instruction

- You supervise and correct misconceptions, but you’re not doing the direct teaching

- Particularly effective for review concepts

The key: Not everyone needs you at the same level of intensity simultaneously.

One child is in Phase 1 (needs you actively). Two children are in Phase 2 (working independently with familiar concepts). Phase 3 happens for everyone during cooking, games, building, or daily life.

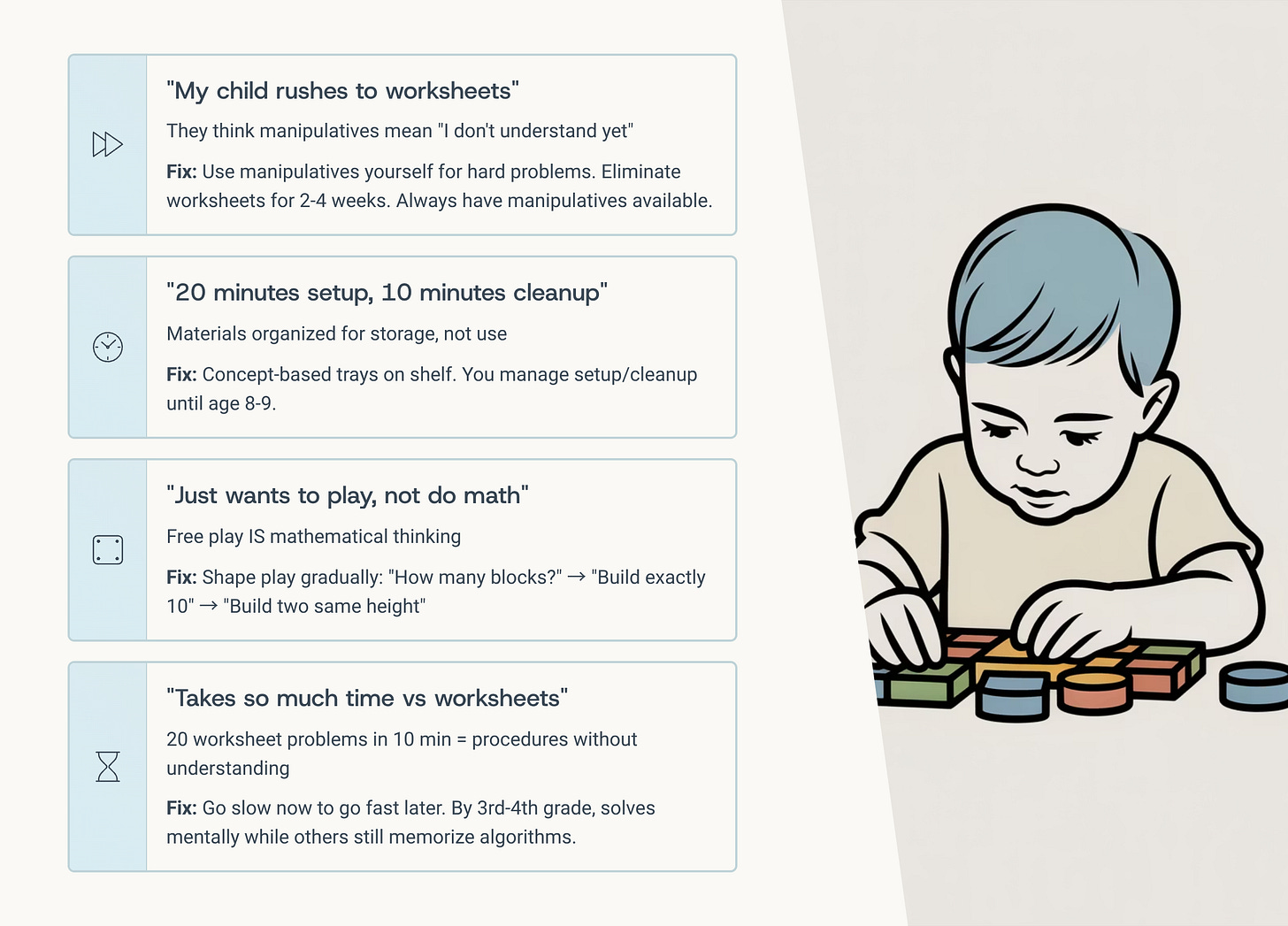

Troubleshooting the Common Struggles

“My child rushes through manipulative work to get to the ‘real’ work (worksheets).”

Your child has learned that manipulatives mean “I don’t understand yet” and worksheets mean “I’m smart.”

Fix this by:

- Using manipulatives yourself for challenging problems: “This one is tricky. I’m going to use blocks to figure it out.”

- Never calling manipulatives “helps” or “tools for when you’re stuck”

- Always having manipulatives available, even for easy problems: “Show me 5+3 three different ways with manipulatives”

- Eliminating worksheets for 2-4 weeks entirely—only manipulatives and verbal explanations

“We spend 20 minutes getting materials out and 10 minutes cleaning up.”

Your materials aren’t organized for use. They’re organized for storage.

Reorganize into concept-based trays that live on a shelf, not in a closet. Each tray comes to the table complete. Each tray goes back as a unit.

Also: Your child is probably too young to independently organize complex materials systems. You set up. You clean up. They just use and put away what they used.

When they’re 8-9, they can manage the full system. Before that, you’re the materials manager.

“My child wants to just play with the blocks, not do the math.”

Good. Let them.

Free play with mathematical materials is mathematical thinking. Your kindergartener building block towers is exploring height, balance, stability, comparison, and counting.

The structure comes gradually. Start with: “I love your tower. How many blocks did you use?” Then: “Can you build one that’s exactly 10 blocks?” Then: “Can you build two towers that are the same height?”

You’re shaping play into mathematical investigation. Not replacing play with instruction.

For older children who avoid the mathematical thinking by defaulting to unrelated play: Give clearer parameters. “You need to build three different arrays that equal 12. When you’ve done that, you can build anything you want with the leftover time.”

“This takes so much time compared to worksheets.”

Yes. Initially.

A child who does 20 worksheet problems in 10 minutes is practicing procedures they might not understand.

A child who solves 3 problems in 20 minutes using manipulatives is building conceptual understanding that will make future learning faster.

You’re going slow now to go fast later.

By third or fourth grade, your manipulative-taught child will solve multi-digit multiplication mentally while the worksheet-taught child is still borrowing and carrying through memorized algorithms.

The time investment pays compound returns.

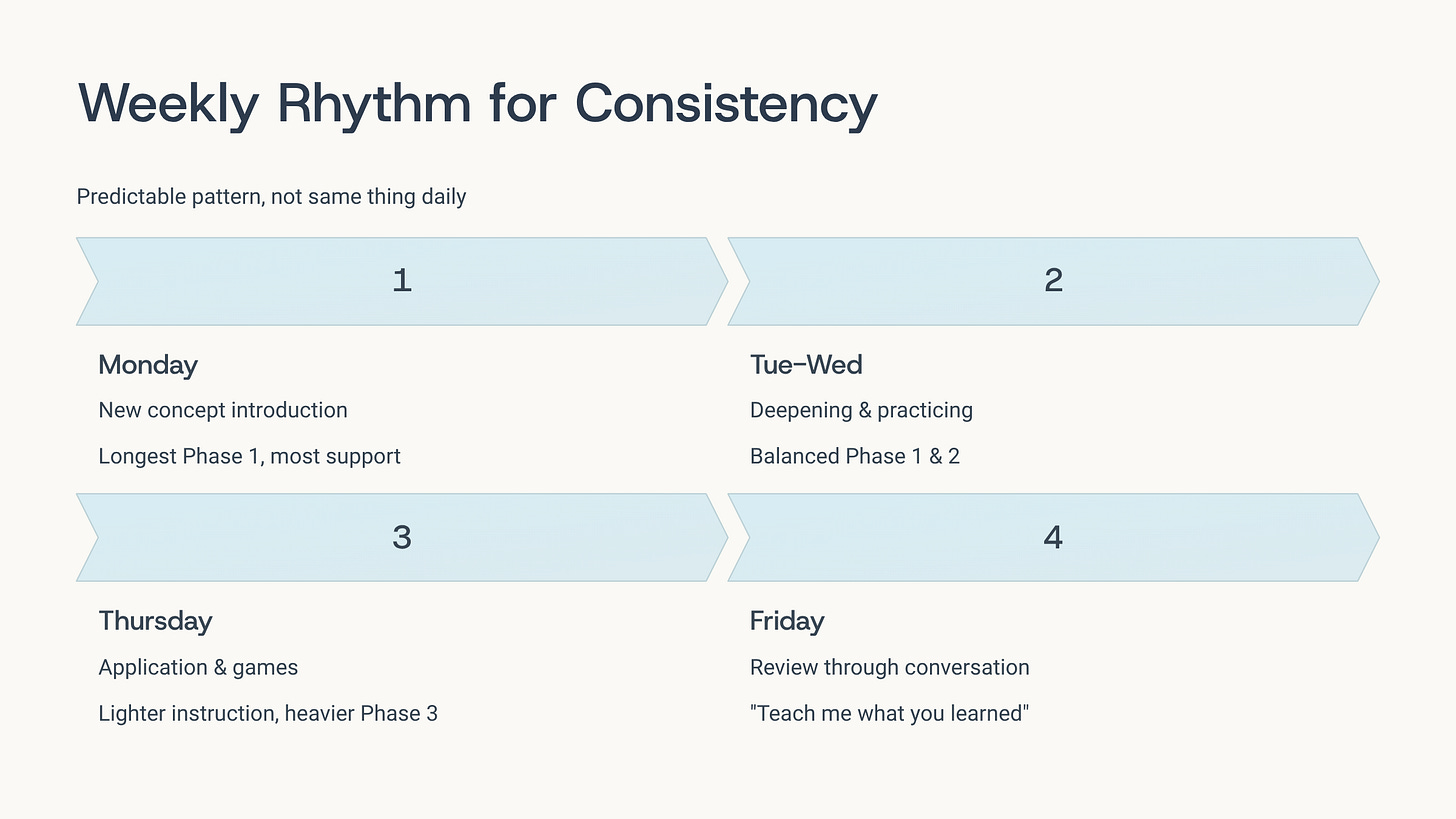

The Weekly Rhythm That Creates Consistency

You don’t need to do the same thing every day. You need a predictable pattern so both you and your child know what to expect.

Monday: New concept introduction Longest Phase 1 time. Most hands-on support from you. Shortest or skipped Phase 2.

Tuesday-Wednesday: Deepening and practicing Balanced between Phase 1 (still building understanding) and Phase 2 (beginning independence).

Thursday: Application and games Lighter on formal instruction. Heavier on Phase 3 real-world application and mathematical games.

Friday: Review and assessment through conversation “Show me what you learned this week. Teach it to me like I don’t know how to do it.”

This is your informal assessment. Can they explain? Can they demonstrate? Can they solve problems without the support you’ve been giving?

If yes: Next week, move forward.

If no: Next week, stay with this concept longer.

This rhythm means:

- You’re not introducing new concepts daily (overwhelming)

- Your child has time to internalize before moving on

- You have built-in assessment without tests

- Fridays feel lighter and more playful

- Your planning is simpler (one main concept per week, not five different mini-concepts)

Making It Sustainable

The manipulative math curriculum works when you can sustain it for months and years, not just weeks.

Sustainability comes from:

Lowering your setup burden: Materials organized for quick access. Today’s materials out before math time. Simple cleanup systems.

Matching to your energy level: Some days you have capacity for complex Phase 1 instruction. Some days you only have capacity for Phase 2 independent work plus a math game. Both are fine.

Letting some days be shorter: A 20-minute math time that happens is better than a 60-minute plan that doesn’t.

Building in breaks: Every 6-8 weeks, take a “math break” week. Play math games. Do math through cooking or building projects. Skip formal instruction entirely. Return refreshed.

Tracking what works for YOUR child: The curriculum gives you the framework. Your observation tells you the pacing. If your child needed three weeks on a concept the guide suggested taking one week, you did it right for your child.

What Success Looks Like Day-to-Day

You’ll know this is working when:

- Your child reaches for manipulatives without being told

- They can explain their thinking clearly

- They notice mathematical situations in daily life: “Mom, we need to multiply to figure out how many cookies we need”

- They solve problems multiple ways and discuss which way is most efficient

- They’re confident with challenging problems because they have tools to make them manageable

- They connect new learning to previous learning: “This is like when we…”

These markers matter more than speed, more than worksheet completion, more than grade-level standards.

You’re building mathematical thinkers, not just children who can calculate.

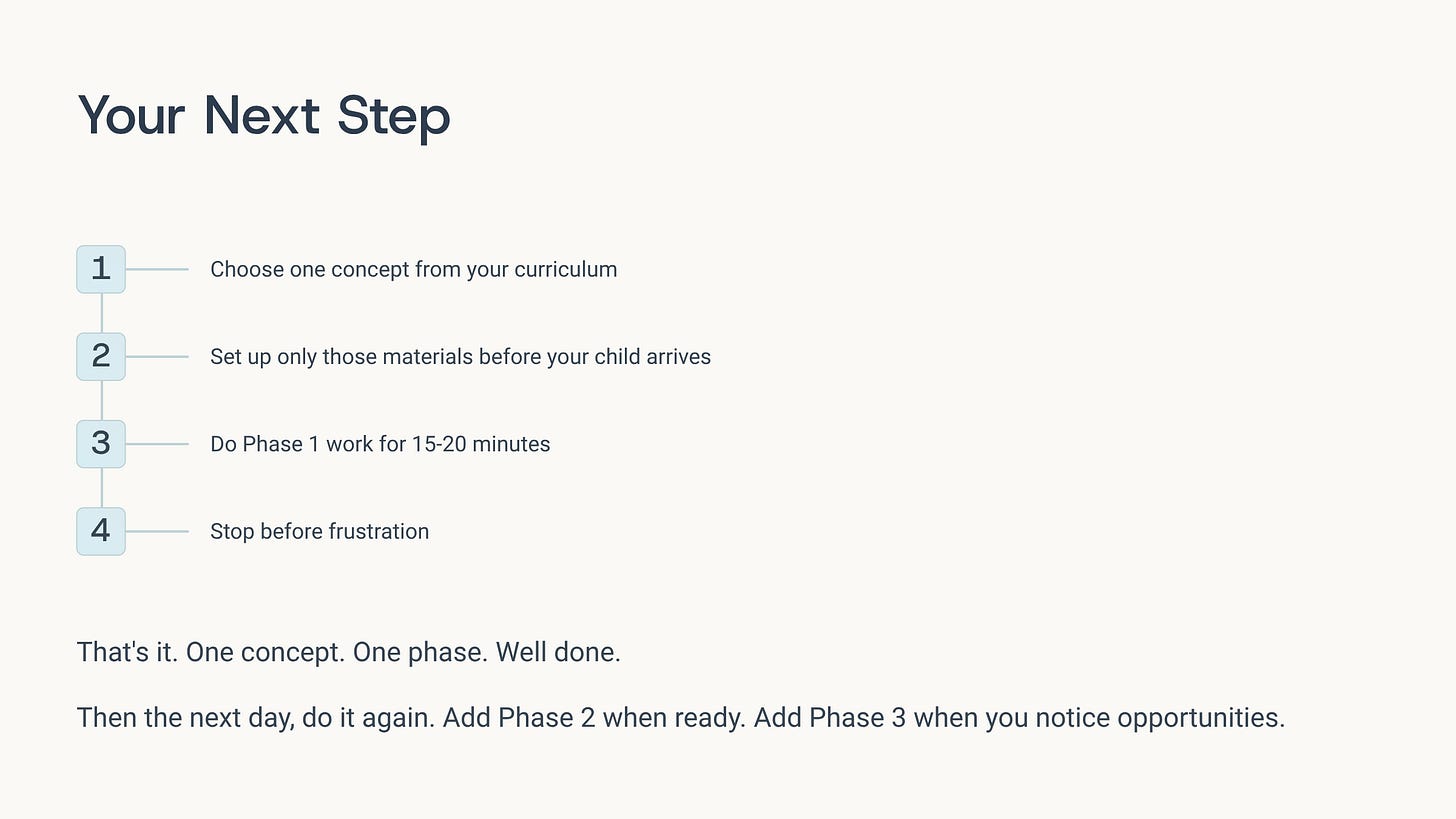

Your Next Step

Tomorrow morning, try this:

Choose one concept from your curriculum. Set up only the materials for that one concept before your child comes to the table. Do Phase 1 work for 15-20 minutes. Stop before frustration.

That’s it. You don’t need to also do Phase 2 and Phase 3 and review and everything else.

One concept. One phase. Well done.

Then the next day, do it again. Add Phase 2 when you’re ready. Add Phase 3 when you notice natural opportunities.

The daily routine builds gradually. You don’t construct it all at once.

You’re not trying to implement the perfect manipulative math system tomorrow.

You’re trying to do 20 focused minutes of hands-on mathematical thinking. Tomorrow, and the next day, and the day after that.

That consistency, over months, builds the deep understanding you’re after.

And it’s actually sustainable for real families, in real homeschools, with real children who ask for snacks and need bathroom breaks and sometimes just aren’t in the mood for math today.

This works because it’s designed for reality, not theory.

Start tomorrow. One concept. One phase. Twenty minutes.

You’ve got this.

LEAVE A COMMENT