The Three Stages Every Child Goes Through When Learning New Math Concepts (And How to Support Each One)

Last Tuesday, my daughter sat at the kitchen table with her pattern blocks, building hexagons out of triangles. She made one hexagon. Then another. Then she stopped and stared at her creations for a long moment.

“Mom,” she said slowly, “six triangles make one hexagon. That means the hexagon is six times bigger than the triangle. But also… the triangle is one-sixth of the hexagon.”

She hadn’t learned fractions yet. She’d discovered the relationship between parts and wholes entirely through building and observing. This is what mathematical understanding looks like when we let it develop naturally.

But here’s what I’ve learned over twelve years of teaching my own kids and working with hundreds of homeschool families: This kind of breakthrough doesn’t happen randomly. It happens when we understand the three distinct stages every child moves through when learning something new, and when we support each stage properly instead of rushing to the end.

Most homeschool math curricula skip the first two stages entirely. They present the algorithm, drill the procedure, and wonder why children struggle to apply what they’ve “learned” to new situations. The workbook says your child knows multiplication. But when she encounters a real problem requiring multiplication, she’s lost.

The issue isn’t your child. The issue is that understanding math requires three distinct stages of learning, and we’ve been teaching only the final one.

Let me show you what these stages actually look like, and more importantly, how to recognize which stage your child is in right now.

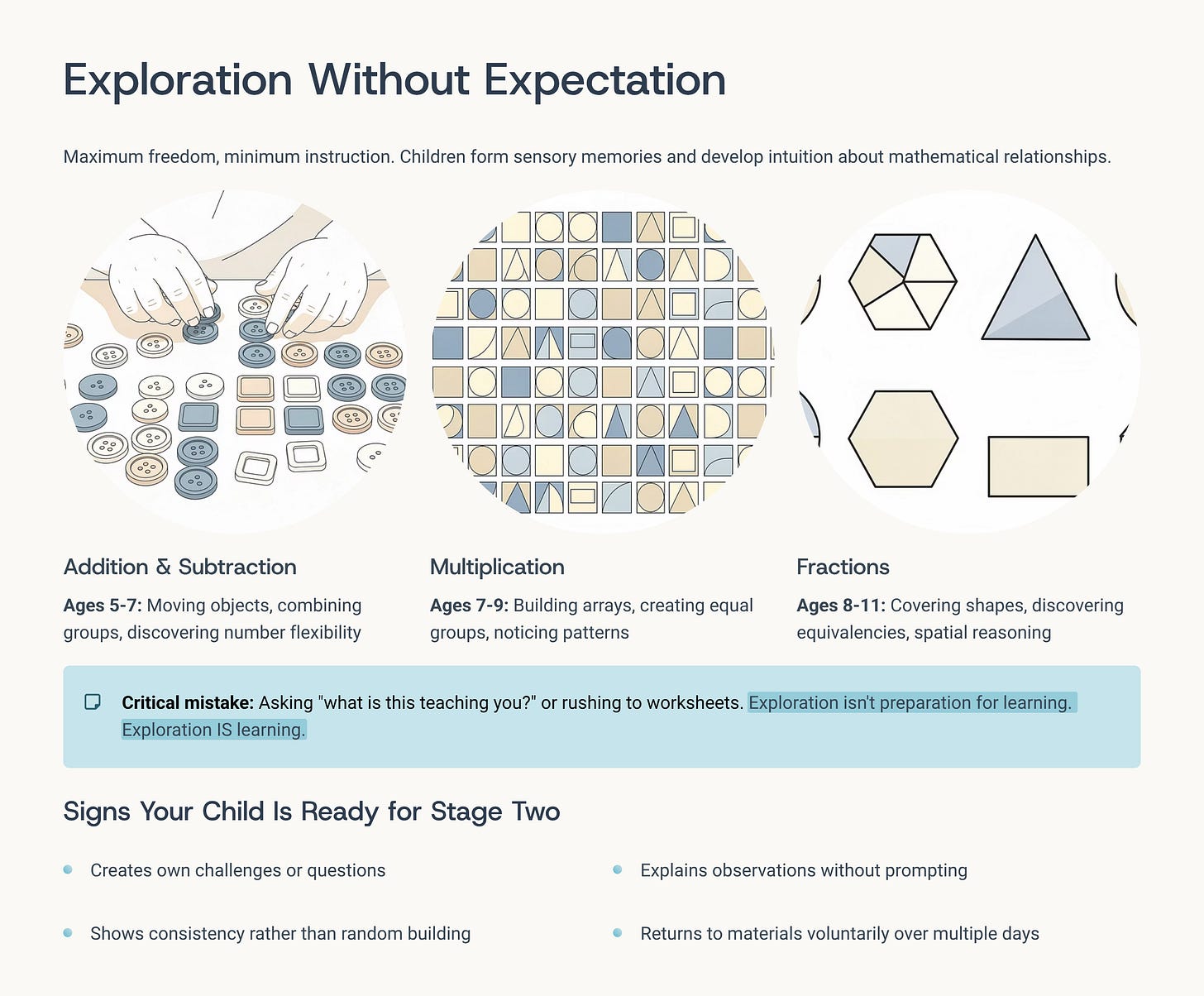

Stage One: Exploration Without Expectation (Ages Vary by Concept)

Your seven-year-old is playing with base-ten blocks. He’s making tall towers, arranging them in patterns, trading ten units for one ten-rod and back again. To an outside observer, he’s “just playing.”

He’s not. He’s building the foundational understanding that will make place value make sense six months from now.

This first stage is where children need maximum freedom and minimum instruction. They’re forming sensory memories, noticing patterns, developing intuition about how mathematical relationships work. The learning is happening beneath the surface, in ways we can’t directly observe and shouldn’t try to assess.

Here’s what this stage looks like for different concepts:

For addition and subtraction (ages 5-7): Your child moves objects freely, combines groups, separates them, notices that six buttons can be split into three and three, or four and two, or five and one. She’s not solving problems. She’s developing number sense—the intuitive understanding that numbers are flexible, that the same quantity can be composed and decomposed in multiple ways.

For multiplication (ages 7-9): Your child builds arrays with tiles or blocks, creates equal groups, notices that four groups of three creates the same pattern as three groups of four. He’s discovering the structure of multiplication without anyone telling him the word “multiplication” yet.

For fractions (ages 8-11): Your child explores with pattern blocks or fraction circles, covering shapes with smaller shapes, noticing equivalencies, discovering that two quarters make the same amount as one half. She’s building the spatial and proportional reasoning that makes fraction operations sensible later.

The critical mistake parents make in this stage: Asking “what is this teaching you?” or “what problem are you solving?” or worst of all, “hurry up and move to the worksheet.”

Exploration isn’t preparation for learning. Exploration is learning.

This stage can last weeks or even months depending on the complexity of the concept. Your five-year-old might explore addition for two months before she’s ready to solve even simple addition problems. Your nine-year-old might need six weeks of exploring with base-ten blocks before place value clicks.

How do you know when your child is ready to move to stage two? Watch for these signs:

- She starts creating her own challenges or questions (”I wonder if I can make this shape with only triangles?”)

- He begins explaining what he’s noticing to you without prompting

- She shows consistency in her explorations rather than random building

- He returns to the same materials voluntarily over multiple days

What you provide in this stage: Manipulatives without worksheets, time without timers, space without instruction. Your job is to be present, curious, and patient. Not to teach.

If you’re using Spielgaben, Gift 7 (parquetry shapes) and Gift 8 (stick laying) are perfect for this exploratory stage across dozens of concepts. If you don’t have Spielgaben, pattern blocks, base-ten blocks, fraction circles, or even dried beans and buttons work beautifully. The specific material matters less than the freedom to explore it.

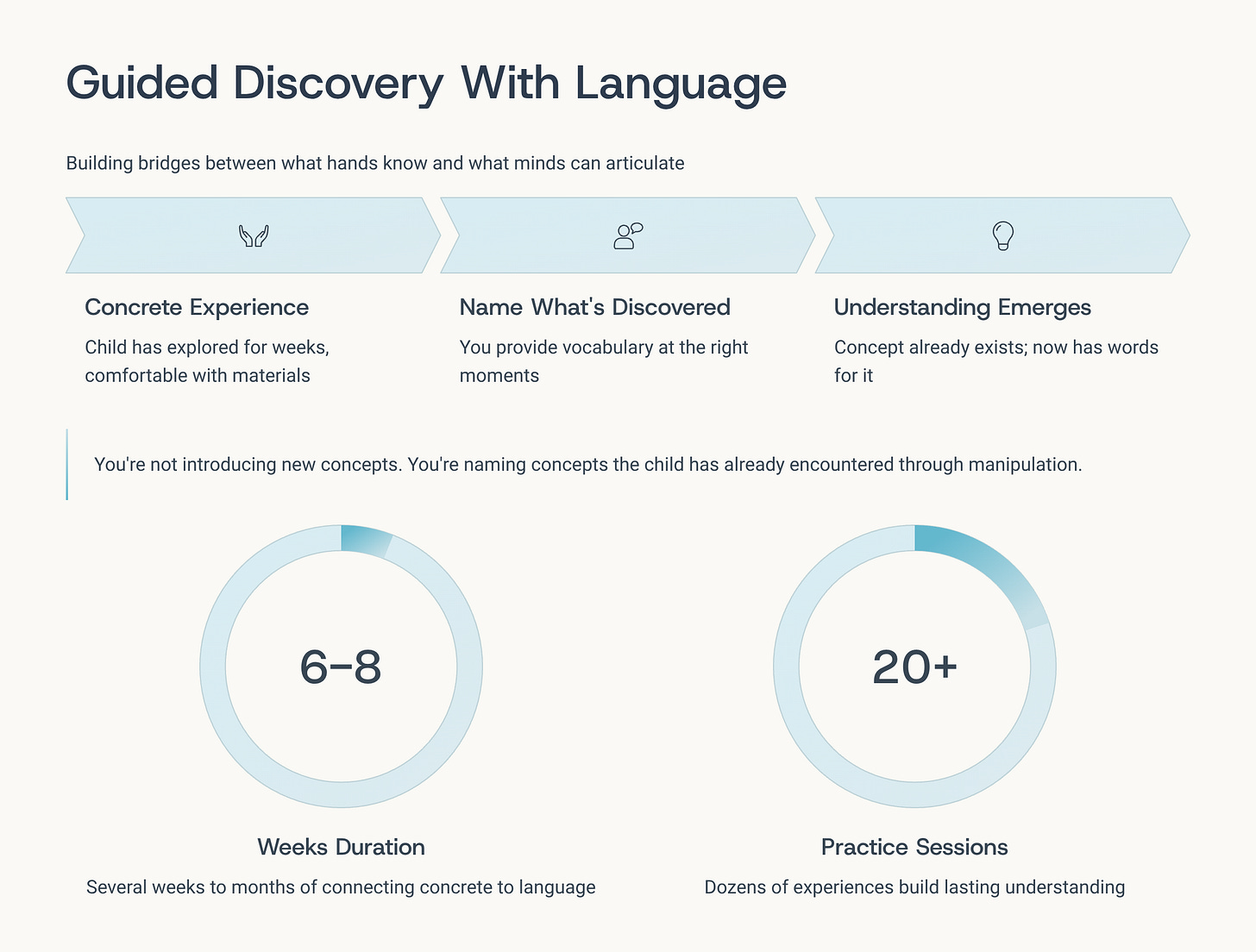

Stage Two: Guided Discovery With Language (Ages Vary by Concept)

Now your child has explored for weeks. She’s comfortable with the materials, she’s noticed patterns, she has intuitive understanding developing. This is when you enter as a guide—not to teach, but to help her name what she’s discovering.

This stage is where the magic happens. Your child is ready to connect her concrete experiences to mathematical language and structures, but she’s not ready for pure abstraction yet. She needs you to build bridges between what her hands know and what her mind can articulate.

Here’s what this looks like in practice:

For addition (ages 6-8): Your child has been combining groups of objects for weeks. Now you sit beside her and say, “You made a group of five and a group of three. Let’s count all of them together. Eight! We can write that: five plus three equals eight.” You’re not teaching addition. You’re naming what she’s already doing.

For multiplication (ages 8-10): Your child has been building arrays. Now you point and say, “I see you made four rows with three blocks in each row. That’s called multiplication. Four groups of three. We can write it 4×3. Let’s count all the blocks together.” The concept already exists in his experience; you’re giving him the vocabulary.

For fractions (ages 9-12): Your child has been covering shapes with smaller shapes. Now you ask, “How many triangles did it take to cover the hexagon? Six? So each triangle is one-sixth of the hexagon.” She knew this already through her hands. Now she has words for it.

The key distinction: You’re not introducing new concepts in this stage. You’re naming concepts the child has already encountered through manipulation and exploration.

This is also when you start posing gentle challenges that extend her thinking: “Can you show me three different ways to make ten with these blocks?” or “What happens if you have three groups of four instead of four groups of three?”

How long does this stage last? Usually several weeks to a few months. Your child needs dozens of experiences connecting concrete action to mathematical language before she internalizes the relationship. One lesson isn’t enough. Twenty quick practice sessions spread over six weeks builds lasting understanding.

You’ll know your child is ready for stage three when:

- He can explain what he’s doing in his own words consistently

- She can create examples of the concept independently

- He can predict outcomes before manipulating (”I think four groups of five will make twenty”)

- She starts getting impatient with the manipulatives because the patterns feel obvious

What you provide in this stage: Questions more than answers, vocabulary at the right moments, challenges that stretch without frustrating. Your role is translator between physical experience and mathematical language.

With Spielgaben, this is when Gift 9 (rings and half-rings) and Gift 10 (drawing materials) become powerful—your child can begin representing what she’s discovering, moving from three-dimensional manipulation toward two-dimensional representation. Without Spielgaben, simple paper and pencil alongside continued manipulative use works perfectly.

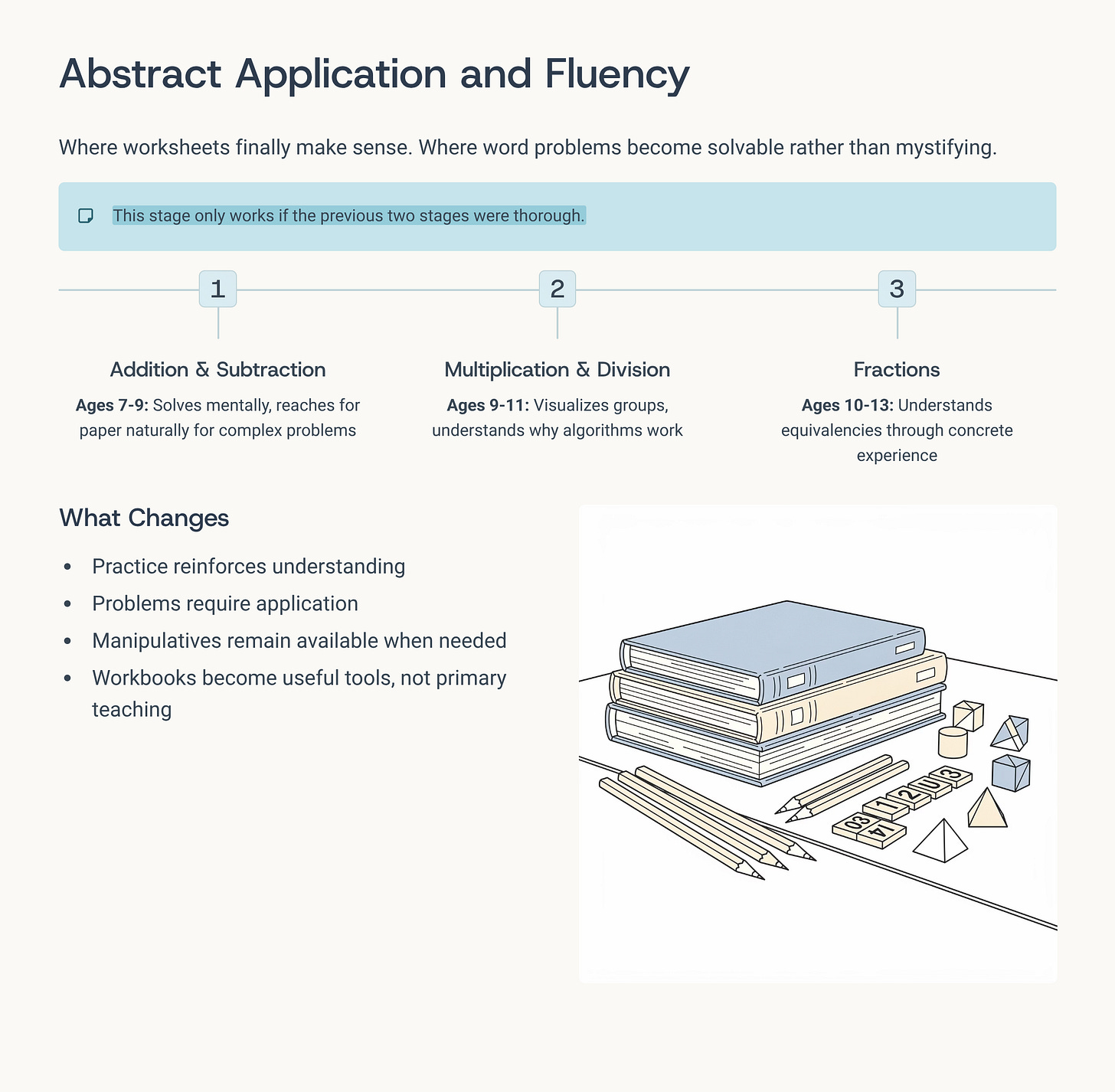

Stage Three: Abstract Application and Fluency (Ages Vary by Concept)

Your child has explored freely for weeks. He’s connected concrete experience to mathematical language over dozens of practice sessions. Now he’s ready for what most curricula start with: working with numbers and symbols on paper.

This is the stage where worksheets finally make sense. Where timed drills don’t create anxiety. Where word problems become solvable rather than mystifying.

But here’s the critical understanding: This stage only works if the previous two stages were thorough.

A child who reaches this stage prematurely—who gets workbooks and algorithms before he’s built concrete understanding and connected it to language—will memorize procedures without comprehension. He’ll appear to “know” math but fall apart when problems get more complex or when concepts need to transfer to new situations.

A child who reaches this stage after adequate time in stages one and two will move through it relatively quickly because she’s not learning something new. She’s simply using a more efficient method for something she already understands deeply.

Here’s what genuine readiness for stage three looks like:

For addition and subtraction (ages 7-9): Your child can solve simple problems mentally without needing to count on fingers or objects. He reaches for paper and pencil naturally when problems get more complex, not because you told him to, but because writing the numbers helps him track his thinking. Worksheets feel like a faster way to practice what he already knows, not like a confusing new requirement.

For multiplication and division (ages 9-11): Your child can visualize groups when working with multiplication problems. She might still sketch quick arrays for problems that are tricky, but she’s not rebuilding the entire concept from scratch each time. When you introduce the standard algorithm for multi-digit multiplication, she understands why it works because she’s already experienced the concept of distributing groups.

For fractions (ages 10-13): Your child understands that 1/2 = 2/4 = 3/6 not because he memorized equivalent fractions, but because he’s physically covered the same space with different fractional pieces dozens of times. When you teach fraction operations, they make sense because the procedures match his concrete experience.

The timeline for stage three varies enormously. Some children move to abstract work quickly and comfortably. Others need to return to manipulatives frequently even when working abstractly, and that’s completely normal and healthy.

What you provide in this stage: Practice that reinforces understanding, problems that require application, and continued access to manipulatives when needed. Your child should never feel that using concrete materials is “babyish” or represents failure. Even mathematicians return to diagrams and models when concepts get complex.

This is when traditional workbooks, online practice programs, and timed drills become useful tools rather than primary teaching methods. Your child practices for fluency, not for initial understanding.

The Mistake That Undermines Everything: Skipping Stage One

I need to address the biggest trap homeschool parents fall into, usually because of comparison anxiety or external pressure.

Your child is seven. Your neighbor’s seven-year-old is doing worksheet after worksheet of addition problems, moving through a grade-level workbook at impressive speed. Your child is still moving buttons around, exploring, building. You start to worry. Maybe we’re behind. Maybe I should push harder.

Don’t.

The child doing worksheets at seven might be genuinely ready for stage three. Or he might be memorizing procedures without understanding, building a house of cards that will collapse in fourth or fifth grade when mathematical demands increase.

Your child who’s thoroughly working through stages one and two is building unshakeable foundations. She might start written work at eight instead of seven, but when she does start, she’ll move through it quickly and confidently because she actually understands what she’s doing.

I’ve watched this play out hundreds of times. The child who races through early elementary math with worksheets and memorization hits a wall around fourth grade when fractions, decimals, and multi-step problems require conceptual understanding, not just procedure following. Suddenly she’s “bad at math” when really, she never built the foundations that would make advanced math accessible.

The child who spends ages 5-8 extensively exploring with manipulatives, deeply connecting concrete to abstract through age 9, reaches fifth grade with such solid understanding that concepts that baffle his peers make immediate sense to him. He doesn’t just know how to follow steps. He understands mathematical relationships.

The question isn’t “when will my child finish stage one?” The question is “has my child had enough time in stage one to build genuine understanding?”

For simple concepts like single-digit addition, stage one might last a month or two. For complex concepts like fraction operations, stage one might last half a year. Both timelines are normal. Both produce children who understand mathematics deeply.

Supporting Your Child Through All Three Stages: A Practical Timeline

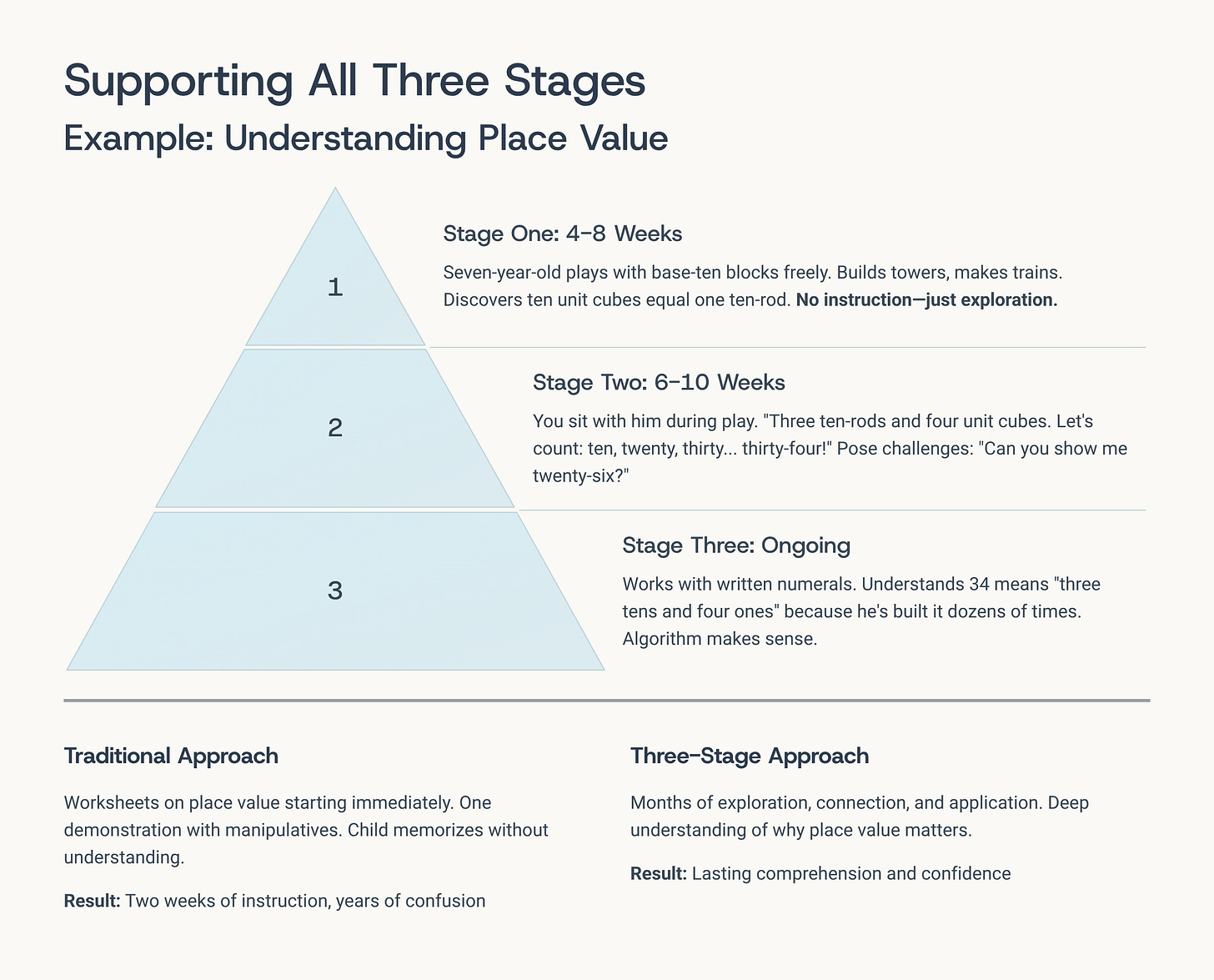

Let me show you what this actually looks like with a specific concept: understanding place value.

Stage One (4-8 weeks): Your seven-year-old plays with base-ten blocks freely. He builds towers with unit cubes, makes trains with ten-rods, creates structures. You don’t mention place value, tens, or ones. You simply provide the materials and let him explore how they relate to each other. He discovers through handling them that ten unit cubes equal one ten-rod in length. This happens through play, not instruction.

Stage Two (6-10 weeks): Now you begin sitting with him during play. “You made three ten-rods and four unit cubes. Let’s count them. Ten, twenty, thirty… thirty-four!” You’re connecting his concrete building to verbal counting and eventually to written numbers. You pose gentle challenges: “Can you show me twenty-six?” He works it out with manipulatives, you confirm and name: “Yes! Two tens and six ones make twenty-six.”

Stage Three (ongoing): Your child now works with written numerals, understanding that 34 means “three tens and four ones” because he’s built that number dozens of times. When you introduce two-digit addition, he may still reach for blocks occasionally, but mostly he can visualize the process. The algorithm makes sense because it matches his concrete experience.

Total time: 4-6 months from initial exploration to fluent abstract work. And those months create understanding that lasts a lifetime.

Compare this to the traditional approach: Worksheets on place value starting immediately, with maybe one demonstration with manipulatives. Child memorizes that the left digit is tens and the right digit is ones without understanding why this matters or what it means. Two weeks of instruction, followed by years of confusion whenever place value concepts appear in new contexts.

Which child actually learned faster?

What This Means For Your Homeschool This Week

You’re probably reading this and wondering where your child is right now in his current math work. Here’s how to find out:

Give your child manipulatives related to the concept you’re working on and step back. Watch without instructing.

If he explores freely, builds, plays, seems engaged but isn’t solving formal problems—he’s in stage one. Keep providing materials and time.

If he’s building but also starting to explain what he notices, creating patterns deliberately, asking questions—he’s moving toward stage two. Start naming what he’s discovering and posing gentle challenges.

If he’s comfortable explaining concepts, slightly impatient with the manipulatives, ready to work more efficiently—he’s approaching stage three. Introduce abstract representation while keeping manipulatives available.

If he’s working abstractly but gets frustrated or makes errors that suggest conceptual confusion—he needs to return to stage one or two for this particular concept, even if he’s advanced in other areas. This isn’t moving backward; this is filling in gaps.

The most important shift: Stop asking “what lesson should we do today?” and start asking “what stage is my child in for this concept, and how do I support that stage well?”

This completely changes your role. You’re not delivering information. You’re providing materials, time, language, and challenges appropriate to your child’s current developmental stage with each specific concept.

One child might be in stage three for addition, stage two for multiplication, and stage one for fractions—all at the same time. That’s not just normal, that’s how learning actually works.

Your job isn’t to move your child through stages faster. Your job is to recognize which stage she’s in and support that stage thoroughly so the next one becomes natural and inevitable.

Next time, we’ll look at what happens when your child seems “stuck” in one stage—and the surprising reason this usually indicates a strength, not a weakness, in how his brain processes mathematical relationships.

LEAVE A COMMENT